If there is a text by which my teaching career has been defined, it is probably the Book of Genesis. I mean the word career rather loosely; it is less about my work within the institutions of academia, which do not only involve teaching (tenure is evaluated on research, collegiality by service, and relatability by community engagement), and more about the continuity between all the odd jobs I worked before I became an academic and what I currently do as an educator in and out of the classroom. The first Bible study I led to a group of high school men in my first year of university was on Genesis. The first high school Sunday school class I taught at a local evangelical church was on Genesis. The first time I taught the Bible in an Anglican church was on Genesis. Before I was twenty-one, I had probably taught Genesis at least three times.

Teaching Genesis, and therefore learning it on my feet, does not encompass all the ways in which I have learned through Genesis. From my earliest years, I was play-acting skits, watching Hanna Barbera and Superbook videos, and attending Sunday school classes on the stories of Genesis. Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph were more like old friends, their stories and shenanigans informing my life almost as a grid. I suppose the fundamentalists might say that that is a good thing, that applying biblical principles to one’s life will make one moral, but I am rather of the view nowadays that selling out your wife as your sister, tricking your brother out of a birthright and a blessing, and boasting to your brothers about your dreams are the stories that bestowed on me a sense of a normalized fragile masculinity. The men in Genesis — patriarchs, if only the word were not so laughable in application to them (Isaac, however, does mean to laugh) — are weak, indecisive, often resorting to half-baked schemes that makes very apparent why they are the wandering shepherds and everyone else from Mesopotamia to Palestine to Egypt is so much wealthier than them and has the urban settlements to prove it.

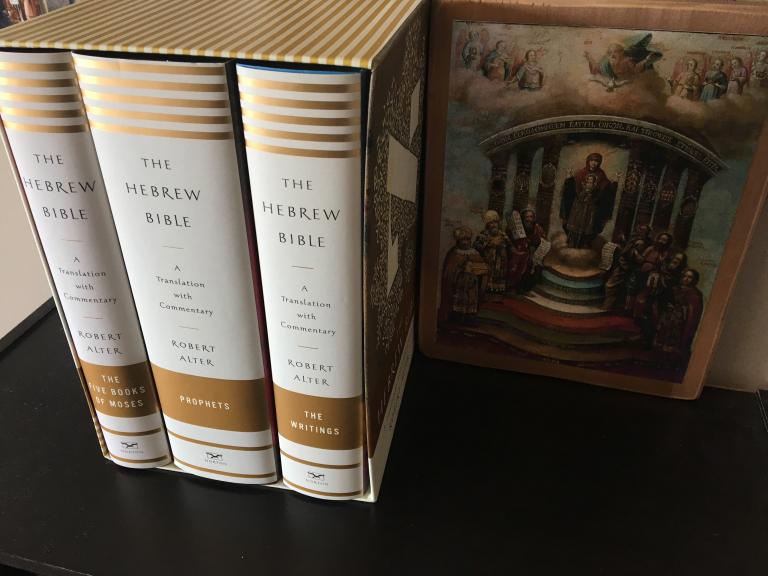

As I learned in Catholic school, the proper hermeneutic that should be taken to Genesis is a womanist one. Hagar, the rejected one, names the Lord as the God who sees her and whom she has seen without disintegrating. The matriarchs Sarah, Rebekah, and Rachel and Leah are the ones who move the story forward, manipulating the men almost as lowbrow comedy. At one point, Rachel steals her father Laban’s household gods, sits on them, and tells him she can’t move because she has her period. Rebekah tells her favourite son Jacob to steal his brother Esau’s blessing. Tamar dresses up as a prostitute and seduces her father-in-law Judah so that she can finally have a child. I learned as a history honours major at the University of British Columbia that that last story, the one of Tamar and Judah, is central to understanding Genesis. Our professor for the historiography seminar felt strongly about the Torah as a mode of history and had us read Robert Alter’s Art of Biblical Narrative, which opens with the Tamar story and contrasts it with Joseph resisting the seduction of Potiphar’s wife. I remember that, as an evangelical, I disagreed with Alter’s assessment of Hebrew Scripture as ‘historicized fiction’ because I really needed it to be the inerrant Word of God. Little did I know that in so doing, I had taken the fundamentalist side of the lawsuit at the University of Washington that gave the school a Comparative Religion Program — conservative Protestant pastors from Bellevue had sued the university for taking a state-endorsed position on religion by offering a course on the Bible as literature and not telling the other side of the story that it was God’s Word — much less that I’d eventually do a postdoctoral fellowship there.

It is hard to dispute the womanist hermeneutic, I think, in any reading of Genesis; the real problem is that evangelicals and fundamentalists whose need to believe in the veracity of the Word of God more than in what it says feel the need to turn it into lessons and principles. The psychological ur-text, if you will, of what has come to be known as the men’s movement of the New Calvinist strand of evangelicalism is Larry Crabb et al’s Silence of Adam, a book that argues that the men in Genesis are weak because they cede their verbal skills to their wives and remain passive. The lesson, though, is not that the women really do drive the story, but that the men should, if only they were stronger. This line of thinking runs down through the apologetics for what evangelicals call complementarianism, the idea that there are set gender roles in which men are warrior leaders and women are captivated followers, captivated being the meaning of the matriarch Rebekah’s name. It’s more or less similar to what would happen if you along uncritically with John Paul II’s theology of the body, parroting his hit-or-miss analysis of male solitude and the feminine genius while failing to discern desire from the body’s experience (which is the real teaching in the catecheses). There is no disagreement here, as I even pointed out when I was of such a persuasion, with womanism as an analytic — it is what the text indicates — but the dispute is over whether womanism is itself a moral orientation to the world or not.

In teaching Genesis, I cycled through these contradictions. I began to do it because I wanted to mentor a group of high school boys at church, and unlike my own antics in youth group when I led Bible studies on Judges and Sunday school lessons on Leviticus and Revelation just because they were fun texts, I felt responsible for their manhood. Drawing from Bible college notes from my stint at Calvary Chapel’s correspondence school and some commentaries that my dad had that ranged the ideological gamut (I was reading Henry Morris’s Genesis Record alongside Nahum Sarna’s Understanding Genesis, as well as the Word Biblical Commentary and the New International Commentary on the Old Testament), I lectured through the text verse-by-verse, creating notes and doing awkward translations from the Hebrew, so that they could get a sense of how God’s powerful word might speak to their questions about what it meant to be a man. I was eighteen, and in my first year of college. The next year, I was assigned to teach the Grade 10 Sunday school class at church, which was supposed to be about basic catechesis — baptism prep, they called it — and I had heard enough of Mark Driscoll’s sermons on Genesis to know that I could teach some of the basic concepts of divine sovereignty through its stories. It is, I am embarrassed to admit, how I became a full-on New Calvinist, which gave me skills and a love for Bruce Waltke’s commentary that I then took into an internship at a Chinese Anglican church and taught Sunday school on Genesis yet again, this time with Jonathan Edwards’s Religious Affections in hand. You have to feel the Spirit, I’d say in class, and that’s how you know that God is sovereign. Through Genesis, I can say that there is continuity from the Jesus Movement to New Calvinism, as the most honest people in that movement might admit (at one point, they were showing documentaries about Lonnie Frisbee at Mars Hill Church in Seattle). The three pedagogical iterations of Genesis here simply crystallized my theology for me as a charismatic Calvinist.

It is a little embarrassing, to say the least, that such fundamentalisms characterize my earliest experiences of teaching. The truth is that there is much more continuity than I care to admit that has followed me into my pedagogy now: the board work that eventually looks like modern word art, the narrative lecturing peppered with personal stories while moving to a climactic point, the act of reading a text together with students live in the classroom. Nowadays I teach Asian American history, social movements, religion, geographies, and urban studies, and like I felt when I taught American religion and cultural geographies and probably as I will feel when I teach the Core Curriculum at Singapore Management University, the imposter syndrome that comes over me has much less to do with feeling inadequate at what I am doing, but suspecting that I am at the end of the day still a Sunday school teacher and a Bible study leader attempting to shore up the inadequacies of a fragile manhood. The earliest bits did indeed follow me into my academic career: around the time I taught this stuff, I also wrote an undergraduate honours thesis on what some comedy movies said that it meant to be a man in 1970s Hong Kong. Clearly, I was obsessed.

I’ve put Genesis away for a while — it has been over ten years, in fact — because I hate it when my feelings of inadequacy hamstrings my performance in the secular university. But recently it has all been coming back to me. First, because my friends at St Mary of Egypt Social Justice Mission have insisted on having a weekly Presanctified Liturgy over the Fast, I have realized that the proper way to go through the Fast is to follow the Sixth Hour and Vespers services, where Isaiah, Genesis, and Proverbs are read. Yet having gotten through those readings and even having reflected about the recent Peterson-Žižek ‘debate’ through them (speaking of manhood), I now find myself at Great and Holy Monday musing on this day’s deep connection to the Genesis story. Perhaps the strangest thing about today’s kondak hymn, which we sing in the canon for Bridegroom Matins and subsequently through the Hours, is that it is about Joseph, the one with the technicolor dreamcoat from the Book of Genesis. After all of what we have been through with the raising of Lazarus, the entry of the Lord into Jerusalem, and Mary of Bethany breaking the alabaster jar over the feet of the Lord, one would think that the entirety of the meditations for Bridegroom Matins would be on what the Lord saw in Jerusalem. There is the fig tree that he curses for its lack of productivity, and that makes it into the tropars, as well as some musings on Jesus using the tree as a cipher for replacing the Jews that feel like later additions to the service that are frankly antisemitic in an Orthodox key. What gives the lie to this supersessionism is that even those meditations get dominated by the figure of Joseph, who does not factor into any of the readings but is the key to the mystery of Holy and Great Monday.

Joseph, we learn from the kondak, canon tropars, and synaxarion reading, is a type of Christ. This too is strange: at Third and Sixth Hour on this Monday, we read the Gospel according to the Holy Evangelist Matthew straight through, and if there is a typology to be had, one would think that it has to do with Holy Joseph the Betrothed, the spouse of the Theotokos. Both the Joseph of Genesis and of the Gospels have dreams, after all, and both of them do not consent to sexual improprieties, the first with the wife of Potiphar and the second with Mary whom he thinks has become pregnant by another. But just as the mother and brothers are the Lord are transcended by those who do his word, there is one greater than Joseph the Betrothed, and it is the Lord himself. Typology, I reflected, is something that I can do because I was schooled in it by Protestant dispensationalists who loved the stuff, seeing the age of the law foreshadowing the age of grace and even claiming Augustine as their teacher. But instead of trying to seize power for God as they do, the mothers and fathers offer Joseph as a type of Christ to comment on power with relation to the colonized people of God. Like Joseph, Christ has entered into the city — the very seat of power — and, through the rejection of the passions and despite what seems to be a loss in the eyes of Jacob, is coming to be enthroned in power.

What comes to dominate the meditations for Great and Holy Monday is the meaning of power in the kingdom of God. The tropars speak of the mother of the sons of Zebedee trying to ensure a place for her sons before Jesus enters Jerusalem, and here, as well as after the entry, Jesus discourses on the contrast of how power is exercised between the Gentiles and in his kingdom. Power is not about domination; it is about being the servant of all. It is what Joseph, like all the weak men before him, has to learn — that you can’t just declare your dreams that the stalks of grain bow to yours and that the sun, moon, and stars bow to you. In the abyss of slavery to Potiphar and an unjust imprisonment when he rejects the advances of his master’s wife, Joseph really learns how to be chaste, to be mortified of the passions that made him so arrogant from the outset. This arrogance is, I reflected, the yeast of the Pharisees and the Sadducees that Jesus deplores, the teaching that the way for a people colonized by the powers of the world is to get stronger. Jesus, like Joseph taken to Egypt, enters the city to confront that very mentality, and in this confrontation he will fall into the abyss. There is continuity, not supersessionist antisemitism, in such a reading between Joseph and the Messiah who fulfills him: the reflection is on how power operates among the people of God, which is to say that the overcompensation of masculine domination over a womanist sense of everyday care within evangelical fundamentalism is about as bad, and maybe worse, than the word-game appeals to tradition that mark the temple authorities and the anti-colonial separatists in first-century Palestine.

With such meditations, I am sent through the mystery of Great and Holy Monday to the beginnings of the people of God in Genesis, where Abraham and his descendants wander between empires and city-states. The comedy is that their weak idiocies imperfectly foreshadow the larger reality that the power of the kingdom is not to be found in overcompensation, but in flawed acts of hospitality, imperfect attempts at the politics of the commons, and a peoplehood that is marked by love when they are not stabbing each other in the back and sleeping with each other’s concubines. Out of that messy family comes Joseph, and from that people also Jesus, and in entering these texts and scenes, it is not I who am teaching Genesis anymore. I am like the children who welcomed the Lord into the city with palms, here to be taught as I was as a little child watching Hanna Barbera and Superbook, play-acting skits, and sitting at the feet of my own Sunday school teachers. Genesis is the school in which I have been and where I continue to stay, for in remaining at the beginning, Bonhoeffer reminds us in his own book on Genesis, is to have the clearest horizon for the future.