Here in Chicago, we are on the Old Calendar. Seeing the Good Friday posts from our New Calendar sisters and brothers, we have a glimpse of what we look forward to next week for Great and Holy Week. To me, there is nothing sad or even awkward about this arrangement, and while some have observed to me that I ‘straddle’ two calendars, the truth is that I have become, over time, very comfortable with the one that I am on. If it ever gets harmonized, I will be happy with that too. As Bishop Benedict of Chicago has observed, the calendars will not save us. Only Jesus does.

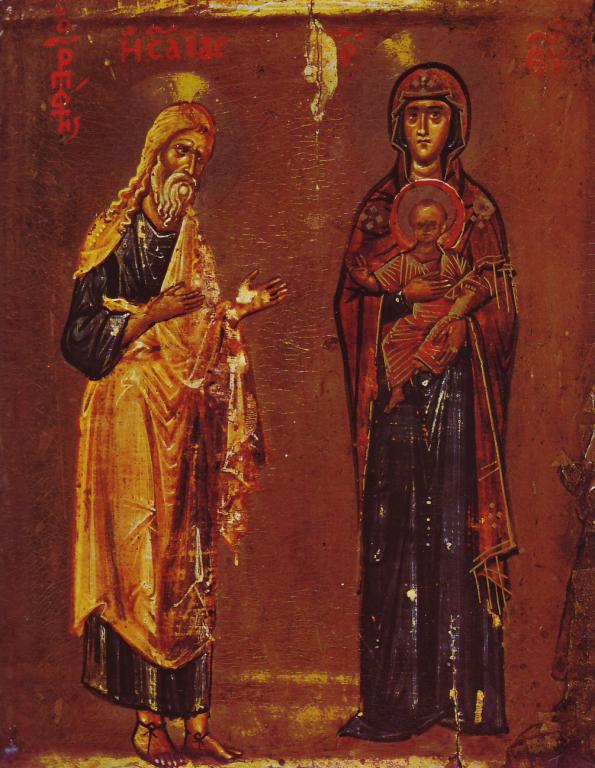

As it is, today we wrap up the Sixth Hour services for the Great Fast. We have read the last portions of the Prophecy of Isaiah, just as we will read the final bits of the Books of Genesis and Proverbs tonight at Vespers as we prepare to enter into Lazarus Saturday. Across Jewish schools and Christian communions, it is known, at least among those who hear the word of the Lord, that G-d is doing a new thing, making a new heavens and a new earth, the former having been destroyed by the scourge of sin and death. More controversial are the Christian interpretations of Isaiah, as even the translator that I read, Robert Alter, acknowledges: the virgin will conceive and bear a son, the vineyard will be taken away from a faithless people and given to others with faith, the suffering servant is fulfilled in the death of a crucified Messiah. These passages, Alter suggests, have come to take on a life of their own within Christianity, with some, especially the fundamentalists, declaring that the prophet is truly prophetic, having foretold the future of Jesus Christ to an unbelieving people who were not worthy of the good news.

The problem with such a fundamentalist interpretation of prophecy is threefold. First, it is antisemitic, with Christians said to have superseded Jewish traditions and rendering void their peoplehood. Second, it is a bit overdetermined, especially as the passages about the ‘virgin’ really are only about a ‘young woman,’ if we were to be honest about the Hebrew, and the suffering of the servant is not really about a messianic figure, but about Israel at the brink of restoration at the behest of her new Persian overlords after the devastation of Assyrian and Babylonian imperial conquests. But third, as Alter provides in his commentary, it is not really fair to how early Christian communities, whose messianic interpretations situate them within Judaism (as Mark Nanos reminds us in the exciting field of New Testament studies he has pioneered as Paul-within-Judaism), encountered these passages in Isaiah in the first place: they made sense of the death and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, situating their encounter with him as Messiah in continuity with the prophetic tradition they were already in. The Great Fast, as an annual re-visitation of our original catechesis, has offered us a chance to re-visit this early Christian reading of Isaiah’s prophecy every day at the Sixth Hour, at noon. In so doing, we join the Holy Prophet Isaiah in doing theology.

That the three parts to the Prophecy of Isaiah can be divided up into First (1-39), Second (40-55), and Third (56-66) Isaiah is not really a matter of dispute, especially among those who have read the book instead of insisting on blind faith that it must have been authored by one person. Benedict XVI has proposed that the biblical prophets, of whom John the Baptist and Jesus of Nazareth are a part, distinguished themselves from the false ones by virtue of them refusing to foretell the future and instead having a direct vision of the glory of the Lord, but that too does not seem to complete capture the visions of Isaiah and those writing within his tradition. More precisely, Isaiah reports to us how G-d, the one who revealed himself as the I AM to Moses before him, sees the world. I suppose there is an apolitical way to read the book, which is to say that G-d’s main complaint with his people is that they worship idols, false gods represented in statues to which they offer sacrifice. The only trouble with avoiding politics in Isaiah is that the text is chock full of it, with the pressure to align with Aram and Egypt against Assyria in First Isaiah, to the new situation in Second Isaiah of the Persian Empire under Cyrus restoring the fortunes of Israel after he conquers Babylon, to the universalist declaration in Third Isaiah that all the nations will be called to judgment and justice in Jerusalem. Isaiah may have a direct line to G-d, but G-d is coming down into a world of empires to judge it for its idolatries and injustices. He did it once at Babel in the land of Shinar. He continues to do so now.

With these visions of G-d coming in judgment on the earth, it is possible to discern how theological development works within Isaiah. The original visions in First Isaiah have to do with one imperial situation: Jerusalem in the kingdom of Judah is being invaded by the Arameans, who are trying to force them into an alliance with Egypt against the rising hegemonic threat from Assyria. Ahaz, the king of Judah as Isaiah starts his career (we are reminded in the famous temple scene when he sees the Lord that it was in the ‘year that King Uzziah died’), is an indecisive ruler, not sure whether to face down the Aramean invasion, not sure whether to join the Egyptian alliance, not even sure whether to ask the Lord for a sign even when the prophet says that he should do so. That is how the ‘sign of Immanuel’ comes about: in response to Ahaz’s indecision testing G-d’s patience, Isaiah retorts that G-d will give him a sign, that a child will be born of a young woman and before he comes of age, the conquests of Assyrian imperial expansion will devastate the land that the feeble alliance with Egypt was supposed to protect.

What is idolatrous in First Isaiah, then, is not just the worshipping of idols, but more importantly the way that the rulers of the earth style themselves as gods, pitting themselves against each other for domination over the land while ‘whoring’ after each other through circuits of trade, as Isaiah memorably describes Tyre and the Phoenicians. To play along with this age of empires, a joke that only the gamers in my readership will get, is to prostitute the people of G-d to these false gods, probably literally because they would have to take on the gods of the empires too. And yet, that is exactly what Ahaz is doing in his indecision, and what Uzziah his father before him had done in trying to play at being priest in the temple and being struck down with leprosy. The vision that Isaiah has, beginning when G-d calls him to prophetic ministry in the temple and he responds, Here I am, send me, is bleak: G-d does not plan to save his own people from imperial destruction, and the idolatrous geopolitical alliances in this game of thrones are not only denounced as prostitution, but also are doomed to wreak devastation on the land.

G-d will deliver his people, in other words, only after they have been destroyed; the proper response to such ‘salvation’ is, Thanks for nothing. It is so depressing that it is almost atheistic; what good is a god, after all, that you might pray to, as the prophet notes that the Judahites do with temple sacrifices, fasts, and observances of holy days, who does not plan to answer any of your prayers for salvation and gaslights you for idolatry even when you are obviously praying to him? Well, there will be a remnant left over to rebuild, the prophetic response seems to be, which again is not all that comforting. Isaiah almost seems cognizant that a listener could draw the conclusion that G-d is pretty much the most useless deity on earth, so the last bits of this section concern a king, Hezekiah, who really does put away false gods and keeps away from alliances, crying out to G-d alone for deliverance from both the invasion of Sennacherib and a mysterious illness that almost takes him soon after. At least this G-d is able to save when he wants to, we learn, although this section caps off with Hezekiah, having experienced salvation, showing off the treasures of Jerusalem to a Babylonian envoy and then, when he is rebuked by the prophet, thinking in his heart that at least there will be peace in his own time. So much for that guy, the response must be, as First Isaiah closes abruptly.

Suddenly, we are in Second Isaiah, with Jerusalem being comforted and restored, we learn, because Cyrus has been anointed by G-d after destroying the Babylonians. The fundamentalists, of course, interpret these passages as the original Isaiah amazingly knowing Cyrus’s name, but the stylistic differences in this section make it far more likely that the writer here is picking up the Isaianic tradition and developing it in a different imperial situation. Here, the people of G-d no longer have the agency to think about political alliances: their land has already been devastated, their kingdom destroyed, and their status relegated to exiles. Whereas in First Isaiah, they were players in an age of empires, they are now in Second Isaiah firmly under an imperial thumb. In this situation, Second Isaiah offers a theological development. It is still firmly within the Isaianic tradition — against idolatry, suspicious of empire, focused on the remnant that will rebuild from the ruins. But each of these themes, without the denunciation of imperial alliances, takes on a new ring. Idolatry, we learn, is when humans project their own fantasies onto material objects; it is what Marx much later called the commodity fetish. Empire becomes useful when it restores the fortunes of G-d’s people, but it is purely utilitarian, as it is a pawn in the larger story of Israel as the suffering servant of G-d who is supposed to display what justice looks like to the nations and gets beaten up for it, especially when she herself falls into injustice and imperial imitation. The remnant here looks like the imminent return of exiles to Jerusalem to rebuild the city into an almost communist utopia, a place where you can buy food without money and drink water, wine, and milk at no cost.

But presumably, communism doesn’t happen as quickly or as optimistically as Second Isaiah thinks it will, which is why with a sudden Thus says the Lord, a declaration that is missing throughout the reflections on Persian restoration, Third Isaiah further elaborates on this post-devastation just society. Instead of on the cusp of imminent fulfillment with the return of the exiles in Persian times, it is now far off into the future. That utopia in Third Isaiah is brighter than ever, one where the people of G-d will be joined by foreigners and eunuchs, where good news is proclaimed to the poor and the captives are released, where the ruins of Jerusalem will overflow with a prosperity that looks like a royal wedding. The nations, the prophet now says in line with the original vision of the mountain of the Lord back in First Isaiah, will flock to Zion to learn justice. Third Isaiah thus offers an interpretation of the exile: the people of G-d had fallen in with the theology of the nations, which is not only idolatry in the simple sense of fetishizing kings and commodities, but also in terms of treating G-d as if he were just another god to be placated with festivals and fasts. That kind of theology, the prophet argues, is sorcery, the kind of magical manipulation of the earth that always goes wrong, wreaking ecological devastation on the land. A theology that is true who G-d is focuses on the making of a just society, one that makes the oppressed happy and delivers the poor from misery. It is so unrealistic that there is only one way it will happen: a new heavens and new earth will have to be made, the poor and the humble will constitute the new city of G-d, and the sorcerers whose fires destroyed the earth will be burned in everlasting flames on the trash heap outside the city.

Each of these movements is a theological development, a new reflection on a new political situation as empires rise and fall, and in this way, the Holy Prophet Isaiah invites his listeners into the doing of theology as it is displayed in the ongoing canonical additions to his book. It is no surprise, then, that the followers of Jesus of Nazareth, who came to be called ‘Christians’ in Antioch, understood themselves as participating in this prophetic reflection, much the same way that the various factions of the Jewish communities colonized in first-century Palestine by Roman occupiers who themselves had experienced a shift from republican rule to imperial authoritarianism claimed Isaiah as theirs. In this world that came together in the passion and resurrection of Jesus, the early Christians saw a further theological development, that the Lord born of the virgin was the sign of Immanuel against the temporal power of empire, that the Lord’s suffering was a sign to the nations that the just often get beaten up, that the Lord’s prophetic ministry gathered to himself a people that included eunuchs and foreigners, poor and prostitutes. With such reflection, the texts that now compose the New Testament canon were assembled and read in Christian assemblies, participating as such in Isaianic theological development as the context of empire shifted yet again.

Every year during the Great Fast, we as Christians are invited by the mothers and fathers of old at the prayer of the Sixth Hour to continue to participate in this theological work, to move from First, Second, and Third Isaiah to what the Holy Prophet Isaiah would see of G-d working in the world we currently inhabit. Ours is an even stranger world than the one observed by Isaiah, his followers, and the Christians who participated in his school. From a people suspicious of empire, Christians, both western and eastern, have not only become complicit in the very idolatrous alliances with empire denounced by Isaiah, but also have made our theologies the driving ideologies of Christian empires themselves, with urban centers like Rome, Constantinople, Kyiv, Moscow, Paris, London, Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, New York, and San Francisco operating as hubs for expansion. In a postcolonial world, many of these empires have also lost their hold on imperial Christianity, creating situations in which Christian churches across communions retain the memory of having had an empire and now grope in the dark toward a future, of whether they should remain in a zombie-like state of imperial nostalgia and white supremacy, develop a different politics that is more democratically aligned, or shrivel up and die. New imperial hubs of Christianity may also be emerging, with Beijing, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Seoul, and Singapore being names of new places of experimentation in how the theology of a nomadic people suspicious of imperial expansion can be fused with the global expansion of market and military dominance.

In such a world of global shifts, the themes of Isaiah remain relevant. The ecological devastation of climate change looms over the horizon, and the question is whether it can be staved off. Waste from economic development pollutes our lands and seas, creating ruins and trash heaps out of the sight of empire, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch showing that we have learned nothing from the meltdown at Chornobyl. Alliances are formed and remade, betrayed and broken, and visions of social justice abound and contradict. The people of G-d continue to be caught within this world. Some, particularly of the Anabaptist persuasion, have observed my journey from the free churches of Chinese evangelicalism through Anglicanism to Kyivan Christianity as deeply problematic, with each step taking me closer to an alliance with empire. This kind of analysis is stuck in the past: the truer state of affairs is that the concept of the ‘Anglican Communion’ was invented in the process of the British losing their empire, and the politics of the Kyivan Church has been messy ever since Kyivan Rus’ was devastated by the Mongols over eight centuries ago. We are all Christians in the wake of empire’s failure, even the Anabaptists who existed to protest the magisterial Reformers’ alliance with local princes, and we all have to reckon with its aftermath in a world that continues to experience neo-imperial devastation, ecologically and socially.

In this contemporary context of the Christian churches reeling from our shared history of empire and acting like either drunks or zombies in a world where our theologies continue to be co-opted, Isaiah can embolden us. What is constant throughout the book, across developments in imperial geographies, is a vision of social justice to which the city of G-d is called through liturgical worship. It is contrasted with lust for power, the kind we have prayed against in every service of the Great Fast when we prostrate at the Prayer of St Ephrem, whether in the sorcery of idolatry, the commodity fetish by which the whoredom of global trade is conducted, or the ludicrous claim that militarization makes ordinary people safer. Such vainglory has a point of convergence in its multiple manifestations: it steals from the plenty of the commons and deprives ordinary people of not only food and water, but also milk and honey. A system of structural injustice is one that is built on everyday enslavements, exploitations, exterminations, and exclusions. In contrast to this idolatrous ideology, Isaiah says that the common people have a God who fights for them, and he is G-d. But G-d plays the long game, allowing empires to wreak their havoc, to devastate the earth, to pollute the waters, and to heap up their crimes against humanity and the heavens. Social and ecological justice are coming, though, even if new heavens and a new earth will need to be made.

I will confess that I have come late this year to these Sixth Hour readings. But having gotten a glimpse of what they are by having practiced them, they have become an integral part of my practice for the Fast. In time, perhaps I will be able to offer theological reflections, even poetry, in an Isaianic key. But that will only be because I have spent time with my sisters and brothers in the prayer that sees the King, the Holy One of Israel, the train of whose robe fills the temple and around whom the seraphim, with wings covering their faces and feet, sing the thrice-holy hymn. The message he sends to Isaiah — that it is only after ecological devastation that the deliverance of social justice will come, that messianic figures suffer and die before resurrection, that throwing in the towel and joining with empire is the truest form of futility because G-d is always coming down to visit the earth and to see with his own eyes the oppression from which he will bring liberation — is on our lips at every Great Fast. Here am I, we say, send me, and there we go, proclaiming till the earth comes to an end that theology is not sorcery and that salvation looks much more like atheism than imperial messianism. The modus operandi of the Creator of the universe, after all, is to come down among us and suffer the oppression that we experience so that we can catch a prophetic glimpse of the just commons through the practices that we are imperfectly enacting even in the meantime. He did it once at Babel, he did it when he made a path through the waters for his children to pass through dryshod, and he will do it again when he makes a highway through the wilderness for us to rebuild a just society after the ecological ravages of empire.