The next time some chump in any of the Christian communions says to me that Jordan Peterson is on our team because of his Jungian-not-really reading of Genesis (it is, as Sam Rocha shows, actually biologically deterministic), I will retort that the ‘debate‘ (a term that is debatable for describing what went down) that was scheduled on his home turf in Toronto between him and Slavoj Žižek took place on the New Calendar’s Good Friday. For Žižek, this day was probably as good as any, and probably poetic because he insists that the only true atheism comes from Christianity, crystallized in the moment where Jesus is abandoned by the Father on the cross. But whoever planned this debate was quite obviously secular, probably unaware that the Christians who are part of the target audience might have had to choose between this farce and the solemnity of church. I, of course, was fine with it: we are still a week out from Great and Holy Friday on the Old Calendar. As far as I’m concerned, today is Lazarus Saturday. For most Christians, though, it was in the middle of the Triduum.

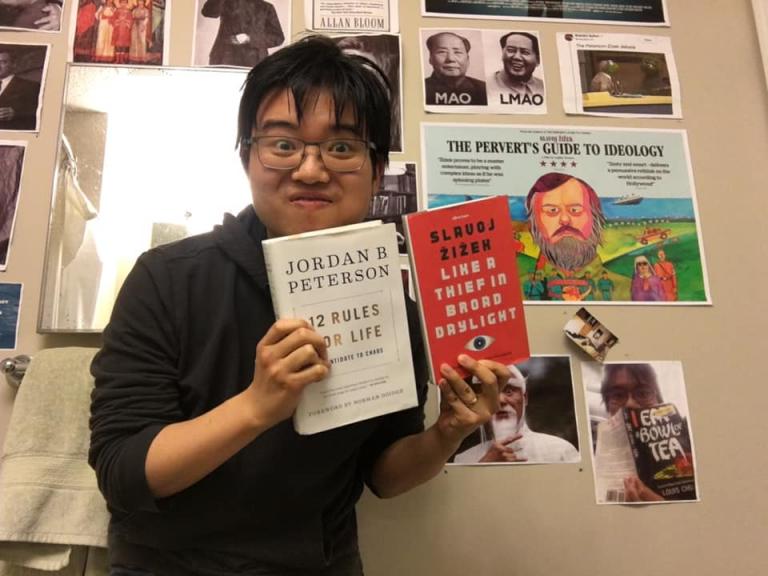

If the advertising were to be believed, the Peterson-Žižek ‘debate’ was supposed to have been a clash of the two intellectual titans, towering figures in the halls of the ivory tower waving expelliarmus at each other with their big sticks. It was my research assistant who convinced me to give away the entirety of my April 19 evening to watch it, with his promises of leftovers in our department’s refrigerator to accompany our witnessing of the ‘WWE of academia,’ if only I would purchase the ticket for the live stream. Having manipulated fifteen dollars out of me in exchange for free food, he brought his girlfriend, who had no context for this debate, and another student in absentia sent her friends, both of whom had varying degrees of knowledge about the gladiators who had been summoned to the Sony Centre. Expecting to get nothing out of this exchange, we also made popcorn. True to the Fast, we did not put butter on it.

The ensuing mayhem was predictably hilarious; it was so delightfully awful that I gave into my impulse to live-tweet it. The discussion was positioned at the intellectual level of an undergraduate classroom where a self-styled model student who didn’t do the readings makes things up about them anyway while the professor, renowned himself for his disorganization and non sequiturs, stares him down with the look that gives away his internal struggle about whether to come down with the rod or the punchline. Peterson, in short, showed up with the ready admission that he had not read any of Žižek’s voluminous word-vomit at the rate of four books per year (at least) and then tried to denude The Communist Manifesto by saying it was wrong about biology. Žižek came with a script that contained lots of recycled material from the books and held Peterson in thrall the entire night with his highlight reel. I, too, have used this technique in office hours, dazzling undergraduates with bits rehashed from my publications as if they were my spontaneously original thoughts. It was effortless because it required no effort: the part where Žižek explains to Peterson his Hegelian approach to Marx through psychoanalysis was a summary of the introduction to his first book, The Sublime Object of Ideology. The best parts were left to the moderator, whose shocked face gave away that he had never seen a Žižek video in his entire life when Žižek, after two hours of what must have been severe self-restraint, finally called him a Stalinist because he was vetting the questions. The most disappointing element was Peterson’s comportment, which gave the lie to his admiration for the lobster as he spent the entire night, while dressed to the nines, hunched over, chest concave, speaking at three memes per second. He really does sound like Kermit, a student muttered.

Marx, as well as Žižek, says that history always happens twice, first as tragedy, then as farce. If the Peterson-Žižek ‘debate’ was the farce — and it really was one — perhaps Columbine was the tragedy. Since last year, critics of Peterson have ourselves been criticized for critiquing someone who was at least doing some good in the world by bringing hope to alienated young people, mostly men, who are said to be living in the post-affirmative action wake of the vacating of white privilege amidst the broader movements of decolonization since the Long Sixties. Being completely empty within, the story goes, they turn to role-playing, which sometimes involves playing at shooting up places because they no longer have anywhere else as an outlet to colonize. So the narrative also went for the so-called ‘Trenchcoat Mafia,’ all two members of it, who shot up Columbine in 1999, and so the tragedy is said to continue apace for every alienated young person, mostly white except for the likes of Seung-Hui Cho at Virginia Tech, who has shot up schools, cinemas, concerts, and streets. I would say that these are mostly men too, but for the young woman who made that perverse pilgrimage to Columbine last week on the twentieth anniversary of the shooting there and wound up dead by her own hand.

The point, though, is that there is apparently a certain class of young people that are allowed to be so violently alienated, hopefully placated by the stories that the likes of Jordan Peterson tell them. Other alienated youth are not so fortunate, of course: think of the policing that goes on in black communities, or worse, the all-out warfare on those whose alienation led them to join the self-styled Islamic State. Some alienated people, apparently, are more terrorist than others, and if you are the right kind of terrorist, the approach to you is pacification instead of policing, with the instruction to clean your room and set your house in order replacing the other option of obliterating you with a drone strike or the War on Drugs. Part of the hidden point as to why nothing has changed, say, on the ban on assault rifles in the United States has to do with such privilege, and the bans, the case of New Zealand has shown, are entirely within the realm of possibility, if only there were the political will to effect them. Therein lies the tragedy, then, that a certain colonizing arrangement is allowed to persist in this world in which some alienated people can do whatever they want and others must be policed and exterminated, and it is that colonial geography that came alive as farce in the Peterson-Žižek ‘debate.’

The persistence of such injustice, both as tragedy and as farce, is tantamount to the longstanding Jewish and Christian reflection that God just might be dead. Holy Saturday is the hiatus, the break in the created order when he who hung the earth upon the waters has not only been hung on the tree but descended into hell, as Hans Urs von Balthasar, that clean-shaven secret German idealist twin of Slavoj Žižek’s from yesteryear, might say. For every twitter theologian who assures us that Žižek’s Hegelian death-of-god theology is heretical, there is both his unnerving repeated citation of ‘Chesterton, Orthodoxy, a very short book’ (as he put it to Peterson last night) and its echoing of Balthasar in Mysterium Paschale that the hiatus radically reworks all theological work that yields the troubling that Žižek might be more orthodox than Hegel; in fact, this is basically what Žižek says in his much more interesting debate with John Milbank in The Monstrosity of Christ. This atheist Christian sensibility can also be found in the tropars for Lazarus Saturday on the calendar that my church is on today; they repeat quite often that Jesus, though as God raising Lazarus from the dead, was also fully incarnate as a finite human being in asking where Lazarus was buried as if he did not know and weeping over the death of his friend as if it really were final. God’s visceral identification with the pain of the oppressed, Žižek agrees with his Lutheran collaborator Boris Gunjević in God in Pain, is the most orthodox of liberation theologies, mostly because it means that the dispossessed are on their own to free themselves, as God is nowhere but in their midst.

Lazarus Saturday, as the end point of the Great Fast, offers to us who are alienated by the persistent colonial structure a course of action. The checkmate moment of the Peterson-Žižek debate was, at least in my view, Žižek pointing out to Peterson, who had gone on and on about how his famously invented category of ‘postmodern neo-Marxism’ retains the binary categories of oppressor-versus-oppressed in the mode of postmodernism, that all that such ‘cultural Marxism’ boils down to is the same kind of conspiratorial bogeyman that the Jews function as in the fantasies of Nazi anti-semitism. It is a fiction that academics of a leftist persuasion are using the category of oppression to foment revolutionary chaos; it is much more true, as Žižek put it, to say that the modes of oppression in contemporary society are so complex that no one really agrees on how to act in this colonizing world, which is why such structures of privilege continue to persist.

But if we were to be honest, oppression has never really been uncomplicated. The Vespers readings of the Great Fast from the books of Genesis and Proverbs come to a culmination in the Vespers for Lazarus Saturday, and if anything, they show that the people of God always find themselves wandering among all sorts of hegemonies, some more benign than others: Cain and his urban descendants in the land of Nod, the Nephillim of old, Babel in Shinar, Ur of the Chaldees, the Pharaohs of Egypt, the various Canaanite rulers named Abimelech, the city-states of Sodom and Gomorrah, and so on and so forth. The record of God’s people in bearing witness to these rulers is also mixed, often less than ethical, and certainly less than moral, especially in the sex-and-violence department. The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom, the Proverbs begin, but they offer a strange kind of shrewdness, warning young people off from being gullible toward their own lust for power and propensity for betrayal so that they can be cunning enough to realize that social justice and friendship with the poor is the only path to prosperity. Both of these threads — the definitive unholiness of the colonized and the sly alignment with the liberation of the oppressed — find their fruition in the raising of Lazarus, in Mary and Martha — just like Hagar and Sarah, Leah and Rachel, Rebekah and Tamar — not really believing what the Lord could do in raising someone four days dead and in Jesus himself deciding almost perversely to simply let his friend rot in his absence so that the glory of the Lord could be displayed. Proverbs warns of the strange-woman, and there is not a single character in either Genesis or in the Lazarus story who can be said to personify Lady Wisdom who has built her house and set her table, or the fulfillment of the ideal wife praised in the acrostic that ends Proverbs, which is read at Vespers for Lazarus Saturday.

In this world of structures and power, life is messy, and the point that is emphasized in the church’s teaching on Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead is that God joins our humanity in our messiness. This atheism is so much better, Žižek argued over and over to Peterson last night, than just giving young people a story to save them from their alienation. To fill the void with any old story to prop up a sense of dominance is to live a lie, and this point was made clear by Peterson himself no sooner than three minutes into the debate when the story that he had told himself about Marxism — that it is to be found in The Communist Manifesto, that it sets oppressed against oppressor, that that upsetting of the dominance hierarchy is not biologically viable — crumbled in the face of audience laughter. The man who had proclaimed the virtues of the lobster standing up straight began to hunch over, his countenance facing downward without making eye contact, his chest fitted with a three-piece suit increasingly waxing concave. This is the farce that parallels the tragedy of Columbine, that role-playing a story that is supposed to give you confidence and meaning will actually make you more empty, alienated, and liable to shoot a place up. Many young men have looked to Peterson for meaning, and in that moment, Peterson showed that he was neither their hero nor their saviour. He was but only one of them.

To this group of alienated young people, Peterson included, Žižek offers the same orthodox Christian atheism as the biblical readings do to those who have prayed Vespers through the Great Fast. There was a joke circulating around Twitter last night that the only reason Žižek would stoop to debate an intellectual unequal like Peterson, much like N.T. Wright wrote two tomes on Paul’s letters in response to John Piper, is to steal his audience. I suppose, but the strangeness of Žižek’s celebrity is that he seems to hate having followers, which became especially evident when he lost the last leftist hangers-on by declaring that he’d vote for Trump if he could. Žižek is nobody’s master; he is, if anything, the disgusting friend you can’t take anywhere because he’ll pick his nose in the middle of the first course at a French restaurant and put his residue in the soup. But perhaps that is the point, that in quests for meaning, both oppressor and oppressed have become obsessed with finding masters who will effect their liberation from alienation. The biblical wisdom is that it is not in masters, but in the wandering messiness that such meaning will be made. As such, Žižek also reminded us last night that he thinks wisdom is stupid. But only in such sites of stupidity is God’s resurrecting presence manifest.