My mother tells me that I could read before I turned two. I do not remember this, but I do recall, faintly, me bringing blocks of alphabet letters to her while she sat enthroned in the bathroom. She would tell me what each of the letters were, how they were pronounced. I am not sure that that is reading, though, because after she came off the toilet, we would have our daily house tour, where I’d point to various household appliances, and she’d tell me what they were in Cantonese. She’d bring me along for errands too, so I got to repeat the whole process while driving through Fremont with stores, banks, and so on, and also items within the supermarkets and women’s clothing stores she frequented.

She tells me that I’d never repeat what she said. She’d say, refrigerator, toilet, Cold Savings Bank, Lucky’s, and I’d just grunt, er. That went on, she informs me, for about six months, and then I caught a terrible fever, one that they thought might claim me for the low infant mortality rate in modernity. But I got through it, and when I got up, then I could bring each block to her and say the name of the letter, and I led her around the house saying refrigerator and toilet and announced Cold Savings Bank and Lucky’s as we drove. I am not sure if these activities indicated that I could actually read, but I suppose it meant that I was a geographer in the sense that I had some early abilities in parsing the landscape. Apparently, she says, it’s how I’ve always learned. Give me an instruction, and you will discover quickly that I can’t do it, any of it. But give it six months and a fever, and I’ll do it better than you.

I don’t really remember my abilities from that time. What does come back to mind, though, is the living room where I played with the blocks, a scene also littered with toy cars and trucks and kitchen appliances and stuffed animals. There is a couch there, and it faces a television, which is adjacent to the fireplace. I spent a lot of time in that space, sometimes pulling from the shelves some huge pictorial Disney books that illustrated the stories I later learned were cartoon movies with songs, other times finding my favourite of all the books there, The Three Little Pigs, which I could narrate so well in Cantonese that once my mother made a cassette tape of me recounting. That area was my playplace, where the activities of measuring out words and finding books and making concepts talk to each other is not altogether different from the tasks of scholarship that compose my day job today. It was also where my parents watched television, which meant that as I sorted my blocks and made my stuffed friends talk to each other and invented commentary on Disney movies I had never seen, moving images were also being pumped into the room.

My first childhood memory begins in this room. It is a crowded scene. People are in the house, on the couch, around the kitchen, and I am trying to play. They are crying while watching the television, and I cannot really tell what is going on. I remember asking my mom what was happening, and she said that these were tears of joy. It was something about minzhu, which I think she said was democracy, but I easily could have mistaken it in those formative years as the people’s Lord, as zhu is who we prayed to: zhu yesou, Lord Jesus Christ. It was all very strange, I thought, because I was not exactly sure why people might cry if they are happy. I usually cried when I stubbed my toe or fell on the ground or (more often than not) wanted to get my mother’s attention. I thought you laughed when you were happy. But perhaps adults are a strange people.

It got even more confusing in a few weeks. There I am, playing with my blocks and my stuffed friends and my toy cars and my pretend kitchen appliances, when the adults are horrified. They are crying again, and someone asks whether it’s appropriate for me to be in the room. Of course it’s fine, I remember thinking, these are tears of joy. Apparently not, I soon learned, and I was whisked away upstairs. The adults cried at home, they cried at church, they cried at dinner.

Eventually, a song began to play on television that caught my attention. I didn’t know what it said, but it sure sounded grand, so I reclaimed my arena singing it. I remember humming it at dinner with one of these uncles who was around, and he, a Taiwanese American man, asked me in Mandarin whether I understood what I was singing. It is my first distinct memory of hearing Chinese and not being able to understand it — that is, what he was asking of me — which felt a bit uncomfortable because I was supposed to have grown up speaking Chinese. I remember being able to make out that he’d make a recording of that song for me, and he did, on a loop, so I could sing it over and over and over, and I did, in my play space.

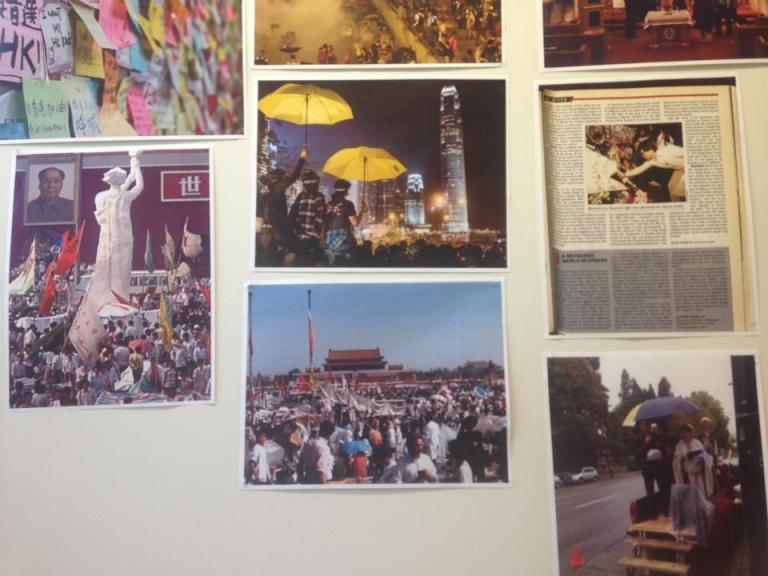

That song was ‘The Wound of History.’ It was collaboratively written by Taiwanese singers in the aftermath of the crackdown at Tiananmen Square thirty years ago. Perhaps its meaning has expanded over time — the words describe how covering your eyes and ears will not make the wound of history that was inflicted by the Chinese Communist Party on the square go away — which is why it seems to be sung at every Tiananmen commemoration calling for redress from the Chinese party-state. At a recent gathering at Purdue, I met one of the guys who was at Tiananmen and was one of the most wanted by the Party, Zhang Boli, who played it at the conference as if he were pounding out the notes to the Yellow River Concerto. He asked me over dinner whether I could speak Chinese, which brought back that old memory of that uncle asking me if I was able to understand what I was singing. I said yes and told him that not only was Tiananmen my first childhood memory, but that ‘The Wound of History’ is the song of my toddler years. He looked stunned when I told him that. Thirty years, he mused, has truly been a long time.

To have Tiananmen as my first childhood memory is not just a cute story that I get to tell at parties. One of the key interventions made by the earliest of psychoanalysts is that what happens in early childhood is formative for a person’s sexual development. It’s one of the things that got people like Sigmund Freud into trouble, as doctors listening to him describe the contours of infantile sexuality used to storm out of his lectures in a huff, but there was a reason why he made these arguments and why his daughter Anna developed them (and thank goodness she did, as her work is so much more lucid than her father’s).

Psychoanalysis is usually mistaken as a discipline that focuses on the unconscious and its operation in everyday lives both when waking and asleep. It is not. As a friend and I discussed recently, the unconscious, especially in Freud, is not that interesting: it’s all just primordial violence and free-floating signifiers. What is of interest in psychoanalysis is how the ocean of the unconscious gets quilted together into a sense of the self, which happens in relation to an ego ideal, more infamously known as the superego. More important than what you want as a person is what you are taught to want and how you are taught to desire. Freud is therefore not afraid to use sexuality to describe these early desires, especially as they relate to the pleasures of bodily touch and the feelings that emerge from those actions. In infancy, we are taught to desire and feel with our bodies, usually by those around us whom we imitate in learning how to be persons, and what was interesting to someone like Freud was how those infantile sensibilities got transferred into situations that we might face as adults, especially in the institutions that circumscribe our lives, like hospitals, clinics, schools, workplaces, friendships, and families. This phenomenon where infantile sexuality lingers in mysterious ways into adulthood is known as transference.

What I’m saying is that Tiananmen and the reaction of the uncles and aunties at my church, of which my parents a part, to it all was one of these early forms of the superego for me. In the post-sixties popularization of psychoanalysis, there is a flawed impression, perhaps due to a misreading of Marcuse’s Eros and Civilization, that the ego ideal is always bad and must be broken, just like bad therapists will insist as a rule that you have to break the transference wherever you find it. The problem with such prescription is that psychoanalysis, as a rule, is seldom prescriptive. It is analytical; its aim is to sort out the mess of the psyche, which includes understanding what your ego ideals have been in the formation of your own selfhood so that you can see it more clearly. It is possible, in other words, to have a healthy superego because you really do have to be taught how to feel. It is also why one of the most important questions that someone can ask about Tiananmen is, where were you when Tiananmen happened? It may not be anyone else’s first childhood memory, but reliving it is to recall a formative moment in history. My spiritual father, for example, was ordained on that very week. It shaped his approach to political discernment through spiritual practices. That story, of course, is for him to tell. I can only recount my own.

I can trace how Tiananmen taught me how to feel, for example, by following what I learned about tears of joy and pain through the events of 1989. That summer, I remember a scene from another house, in another living room, where the lights were dimmed, and the adults, the same ones who were in our home, had their eyes closed, some of them crying, some with hands lifted, facing projected words in English. My mother was there, late into pregnancy with my little sister, her belly moving up and down as she kicked, but she seemed oddly at peace. When we got home, I placed my head on her tummy as my sister kicked, and I asked my mother as she lay on the couch in my play place if she was sad, confused as I was about the many uses of tears that I was learning about. She said that she had been praying. It’s how I learned that prayer was not simply something that we did before eating and had to end with the magic word amen, which was somehow different from a man. It was a bodily practice, one that sometimes involved tears, which could also include chanting texts. The songs the adults were singing, of course, were not the liturgical texts that form my prayer life now. They were non-denominational Christians, and our pastor had at that time traveled six hours south from the Bay Area to Fuller Theological Seminary, where he studied church growth with John Wimber and C. Peter Wagner, the founders of the Vineyard Movement with the ‘third wave of the Holy Spirit,’ and thus brought home these prayers that my parents called ‘Vineyard songs.’ It’s also how I started singing, in addition to ‘The Wound of History,’ songs like ‘Draw Me Closer’ and ‘More Love, More Power.’ They all had, I felt, the same vibe, which probably explains both my theological promiscuity and my eclectic musical tastes. It also taught me that prayer involves the entire body.

Soon, my sister was born. My mother had to go to the hospital, which is how I learned that this health institution was not only for sick people and that I too had been born in one three years before. It fell to my father to feed me, and thus we went to the McDonald’s across the street from Washington Hospital in Fremont. I did not know what he was feeding me and therefore was suspicious of it, and in desperation, he held up a Chicken McNugget and described it to me as a chicken chip chip. I knew what chips were — we had lots of shrimp chips from the Asian supermarkets — so I was intrigued by chicken in chip form, dipped in what he described as sweet and sour sauce. We then went to the hospital, where my mom lay on a bed, and I could not be convinced that she was not sick. A visit to the surgery a year later to see my friend who had had open heart surgery convinced me that I was not crazy; people lying on beds in hospitals are, if not sick, generally weakened, and both my mom and sister had to stay put for three days. My mother knew exactly how to parent me through this time. When I visited the first night, she gave me saltine crackers with a piece of cheese. The second night, she gave me a pickle. On the third, I got a slice of salami. I associated these foods with the birth of my sister and my mother’s maternal care, and even now, when I am looking for comfort food, I will gravitate to chicken nuggets, cheese and crackers (or bread), pickles, and salami slices. I also have now learned that those were the left over parts from the hospital meals that my mom didn’t like, which means I got seriously played by my superego figures and know what I am doing when I get my comfort foods now, and do it anyway.

A month afterward, I was in my play place, minding my own business with the blocks as the television was on, and the whole house began to shake. Just as in the case of Tiananmen, I ran toward the television, thinking that this is where you get information and emotions about what’s going on. My mother and the church’s official babysitter, holding my newborn sister as she came to help my mother get through the first month after giving birth, shouted at me, that I was a fool, that you never run to the fireplace in an earthquake, which is what was next to the television. The babysitter, a formidable Vietnamese Chinese grandma, instructed us to get under a door frame, the sturdiest part of the house. A few years later, I went on a field trip to the planetarium in San Francisco, where they had an exhibit replaying the Loma Prieta earthquake with a simulation to a video. I really could have died, I reflected, if the bricks from the fireplace had fallen on me like the cans in the supermarket fell on those poor people. The Bay Bridge collapsed that day, in fact, hurling cars with people in them into the San Francisco Bay and creating a crack in the City, which is the only name those of us from the Bay Area have for San Francisco. We learned shortly afterward that my dad had been scheduled for a meeting in the City, but that it had canceled at the last minute. He could have died too, if he had been on that bridge.

History did not end for me in 1989, as Francis Fukuyama believed it did (and then had to eat his words when the Beijing Spring was crushed). It’s when it began. I remember ever so faintly the images of the Berlin Wall falling and my parents watching the television intensely, but those images are mixed in my mind with those of Sesame Street and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. What I can recall more clearly is that shortly after these events, I was sent to preschool, a place where they sang songs I didn’t know, spoke an English with a different inflection than I had ever heard, and existed independently of my mother, who, instead of keeping me in a children’s corner while she had Bible study or took me to smear chocolate pudding all over my face at the mother-son program for toddlers, had to drop me off and pick me up later in the day. Of course, I also had that experience at church with the nursery, but that was my mother delivering me over to the Vietnamese Chinese grandma and the uncles and aunties, all of whom were family. With preschool, I think I felt for the first time that I was not with my family anymore, even in an extended sense, and I had to make sense of it with the emotional tools with which I had to make do. I’m not sure I cried, although I probably did, but I do remember being confused, that there was a whole new world outside of my parents and their uncle and auntie friends who ate and cried and prayed and laughed and hung out in living rooms when they were not in church.

What, then, does it mean that Tiananmen is my first childhood memory? Probably nothing, to be honest, in any cosmic sense. Ien Ang complains in On Not Speaking Chinese about the appeals at the time throughout the ‘Chinese diaspora,’ if there really is such a thing, for solidarity around Tiananmen because of a nationalistic sense of Chinese blood kinship. Blood, however, is a very problematic basis for connectedness, as watchers of Game of Thrones will know all too well. The only connection I really have to Tiananmen is that it is my first childhood memory, but not exactly of the hyperreal images on the television either. It’s that I experienced the gamut of emotions with the uncles and aunties at the extended spiritual family of my church, which included my parents’ feelings, and in so doing, I learned the range of the language of tears, of joy at the unleashed freedom of political agency and of devastating grief when those dreams are crushed. Through Tiananmen, I learned to cry, to hope, to pray, and to worship, and while my practice of those actions have continued to morph with discernment over the course of my life, I cannot deny their source. They come from my family, which is not merely biological, but extends into the extended family of the church I grew up in, one where Cantonese merged with Mandarin because we all inhabited the same domestic spaces and called each other sisters and brothers. This capacity to feel blurs the line between my spirituality and my politics because it is from the space where family, work, and play coincide that I approach the world, feeling it, which is the only way to discern what to do in it.

It has been thirty years. I too will never forget, because I cannot.