At Matins on the Sunday of the Prodigal, we begin to sing ‘By the Waters of Babylon.’ As if to dramatize the stichera that speak of the son who demanded his father’s inheritance and then wasted it in a foreign land, the exiled Hebrews in the psalm sing a haunting song about sitting by the waters of Babylon, unable to sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land. Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia caps each verse, almost in cruel irony, especially when they bless those who might dash the little ones of the Babylonians against the rock as it was done to those they conquered.

That was last week; the time has gone by quickly. I was away at a conference at Purdue University, where we spent three days deliberating over the role of Christian social activism in Chinese societies. A few activists who were on Tiananmen Square for the Beijing Spring in 1989 were there. So were some at the Sunflower Movement in Taiwan and the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement. It was a good smattering of pastors, activists, and scholars, all brought together by Fenggang Yang, who has emerged as one of the major figures in bringing folks from different ideological factions in Chinese intellectual circles together. Indeed, in 2013, he took part in getting the ‘Oxford Consensus‘ signed, a statement that agreed on the role of intellectuals in Chinese societies and the importance of their ideological debates.

What this meant was that I wasn’t at home for Vigil or Divine Liturgy on the Sunday of the Prodigal. In fact, that morning, I was singing ‘How Great Thou Art,’ ‘Amazing Grace,’ and ‘This Is My Father’s World’ with this group of people at a Sunday service. I deftly avoided taking communion by staying inconspicuously in my seat as folks went up for it. It was, for all intents and purposes, a Protestant conference, if not dominated at least by those from the mainland by those in the Reformed traditions, and while the pastor who led communion said that denominations didn’t matter in Christianity — not even the Roman Catholic one, he emphasized (he didn’t know there was an Eastern Catholic in the room at that point) — I did not want to add scandal to the scandalousness of our historic schism by pretending that it had all been patched up already.

Protestants, especially the Chinese ones, sometimes note my lingering in such circles, as well as my constant writing about them, and wonder if I miss them. In fact, when I showed a draft of a recent essay I submitted on Asian American evangelicals and their Internet politics to an evangelical friend of mine, he said it was like reading me writing about an ex-girlfriend. I replied that that was far better than being told, as I have also been accused of, that I had an oedipal complex with evangelicalism. Returning to this kind of space did things to my body that I had not felt in over fifteen years. Halfway into an afternoon session of pastors sharing about their theologies of social activism, I slumped, and slumped, and slumped, almost involuntarily, and then I felt a great desire to gather all the young people in the room to got to a basement and play something like Super Smash Bros.

As it was, I could not help last Sunday reflecting on what it meant that I was in such a Chinese Christian space, normalized almost as Reformed Protestant except for some of us Hong Kong and Taiwan scholars (for the purposes of this conference, I was in their number, presenting on a panel on Hong Kong), on the Sunday of the Prodigal. Perhaps, I felt, I might have been returning as a lost son, but that interpretation felt facile, and as I’ve written, I’ve never actually stopped calling myself a Chinese Christian. I am, after all, a Christian because I claim the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ for my own through personal faith in him, and I am Chinese — not a national, by any stretch of the imagination, and not even a Hong Kong person really, but literally because I was brought up in Chinese communities on the West Coast. I could call myself an exile from the Chinese Protestantisms of my youth, but I don’t feel one bit exilic at the moment, having found a home in the Kyivan Church. I did not return from a wasteland back to my father’s house, as the stichera say that the Prodigal did, as I have not been ecclesially homeless since my chrismation. I have found where I belong; there is nowhere I need to return.

But as I returned to a space associated with my youth, I could not help but feel that a bit of my own current fantasizing about Chinese Christianity has also been burst. I often say that becoming Eastern Catholic has enhanced my sense of what it means to practice the faith as a Chinese Christian, but I did not expect how normative it would be to associate Chinese Christianity with a kind of de facto Protestantism. It was hard, even, for some of my interlocutors to think outside of the narrative that they told about the Reformation and the passage of Christianity to China. At the end, we even got into a contentious conversation, instigated by me, about the place of Chinese Catholics in this discussion. In fact, I found a unique grace that on arriving back in Chicago, my friends at the Center for World Catholicism and Intercultural Theology at DePaul University texted me to tell me that a major and emerging scholar of Chinese Catholicism, Mary Yuen, was in town to give a talk on the subject. Yuen also wrote a chapter in the book I edited on the Umbrella Movement. Of course I went, and then stayed afterward for drinks. It tied my experience neatly together.

That experience, I feel like, has something to do with Chinese Christianity being an arena that shows how it is that the oikoumēnē continues to be divided. It is not so much that the divisions exist because of hostility or polemics. It is just that it is hard for people, it seems, to conceive of their own practice of Christianity as not normative. Perhaps, as some conference participants pointed out, my experience is so ‘postsecular’ — I kept using the word, so they used it right back at me — that I’ve become fluent in a number of churches and denominations in Chinese Christianity. But there is, if you will, a kind of feeling of permanent exile within Chinese Christianity, and it is not just because there is a sense of diaspora with a dubious claim to too many motherlands because there are too many Chinas and Chinese societies. It is also that there are too many Christianities.

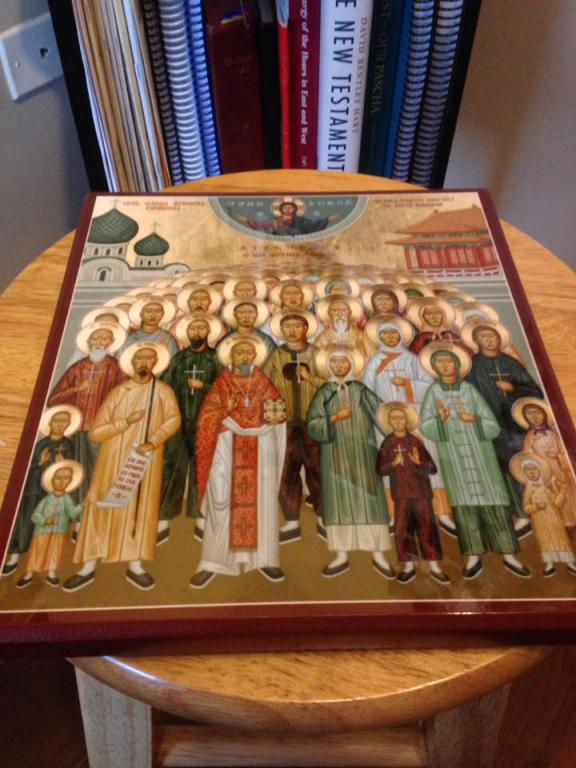

Here, I think, is where reflections on the Sunday of the Prodigal become clearer. Within the parable, the going into a foreign country is the fault of the younger son himself. But in the Lukan context, and then in the context of history, diaspora and exile into a wasteland also has something to do with colonization; in fact, the Lord is telling the story to Pharisees who are scoffing at the tax collectors and sinners gathered around him because it is they who are blamed for their permanent exilic condition under empire after empire claiming Palestine as theirs. So too, the icon of the Holy Martyrs of China, which became a gift to me in my spiritual contemplations as I became Eastern Catholic, makes it clear that these holy ones, who are tied across Orthodoxy, the Latin Church, and Protestantism, are martyrs of the Boxer Rebellion, a grassroots uprising that had imperial sanction that killed off Christians because of some emerging notion of China as a ‘nation’ that had been slighted by Western powers. If there is anything to account for the divisions of Chinese Christians as symptomatic of the scandalous persistence of schism in the oikoumēnē, maybe it too has to do with the nation, especially the tunnel vision of trying to make all Christian theology apply to a Chinese national situation, or to form an identity as a Chinese society. Nationalism in this sense is responsible for the myopia of not being able to see outside of one’s tradition, for the traditioning itself may have been overdetermined.

I wonder, then, if the Sunday of the Prodigal offers some reflections on the task of scholarship on Chinese Christianity in a global, ecumenical sense. Certainly, such scholarly work does require a sense of secularity to not get stuck with the dangers of nationalist myopia, but perhaps the wasteland and the sense of exile into a ‘foreign’ country has to do with the fractures of Chinese Christianities that do not recognize each other as Chinese or Christian. Realizing that we are eating slops from the pig’s trough, it is together that we must rise and go to our Father’s house to tell him that we are unworthy to be his son. But until then, we still weep at the waters of Babylon like those who dream. Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia.