Recently, I was at a talk given by the poetry professor Timothy Yu, and while I could name them and those with me, basic etiquette informs me that collegial relations are of a different order than family. The talk, simply put, was brilliant. It was also about poetry, which I did not expect to understand, except that the opening moves that were made situated the exegesis of some poems in one of my core disciplines, Asian American studies. I was surprised that I understood it and that I got on so well not only with a teacher of poetry, but with poets themselves and scholars of all manner of literary genres beyond my comprehension as a geographer.

It’s funny, now that I look back on it, that I thought I might have become an English major, even taken honours. Unlike most Asian Americans of the class that ushered their progeny into university, my mother and father had encouraged me to take English as a major, mostly for the practicality, they said. This is not what most other parents would say, but it was what mine said, with the hope that I’d grow out of the phase where I had vowed to study the Chinese church. For most other Asian Americans, it seems that the act of courage is to study English. For me, being courageous was to become a history major, in fact in an honours program. The idea, as I recall it, was that English would prepare me to be a lawyer, and history would do something similar, but maybe it would be second best. Yet that move set the stage; from then on, the arc of historiographical writing became familiar to me, a skill that I took into geography with me (as my dissertation supervisor never ceases to remind me), whereas the questions of genres and meter and syntax became increasingly foreign to me, until much later, when I discovered that as an academic, much of what we do is writing.

It was along the way that I feel like I lost sight of what a poem was and why poetry was important. I remember late into my undergraduate career that I took an English class on the Literature of British Columbia, and we had to read poetry. What’s it all for? I found myself asking as I read it. The prose was so much more interesting to me; it was, after all, about something. Poems I could scan at a glance. I suspected that the art was to read them more slowly. But who’s got time for that?

It is a little stupid, because as I reflected on how my career actually turned out — I did get to study the Chinese church, which means that I’m tethered to it by the book project over which I pull my hair out nightly — it all started with a poem. It was, as I’ve said before, because I read Baldwin, didn’t understand it, and was assigned to write a poem about it, which ended up being a terrible but rather imaginative poem about bringing a white girlfriend to my Chinese church and her being rejected through microaggression. I keep it tacked to my wall in my home office, and I often re-read it to remind myself of how far I’ve come from my adolescent fantasies. It is not, by any stretch of the imagination, a good poem, although I got an A+ because of an apparently compelling reading that I gave of it in class.

I still remember the process I took to write that poem. By virtue of no one attending the creative writing workshop offered by our high school chaplain except for me, I became the inaugural editor of the our school’s literary magazine Sea Changes. Fr Harry, the priest who advised me, offered a poetry workshop for anyone who wanted to learn the craft. As it was then, so it is now: I have always professed disdain for poetry, feigning on the one hand not to understand it and pretending on the other to be completely incompetent at the craft. But anyone can write a poem, Fr Harry said, and as I was the editor, I had to attend.

Fr Harry taught us to write five words that we associate with a topic on five sides of a page. He then said to start writing words that might be associated with those words. Soon, he said, we’d have a bunch of words on a page, and then we could begin to arrange them. This, he said, was how to write in free verse. I liked the process a little more than I professed at the time; it certainly beat having to force everything, as I thought poetry was, into meter, verse, and rhyme. It was with this process that I wrote the poem on Baldwin, through what basically turned out to be free association, which is the only way that someone can come up with the Chinese church while reading The Fire Next Time and then proceed to build a career on it.

I suppose it is because of the free association by which I arrived at the topic of study that is an overshadowing presence in my life now that I have always written off poetry as self-expression. I really don’t give a damn about someone else’s inner feelings, and frankly, neither does anyone else, which is why the more reflective posts on this blog tend to get the fewest reads. What Yu’s talk reminded me of, though, was a creative arts event that my colleague Patricia Nguyen hosted at the closing of Axis Lab in Uptown here in Chicago. For me, it was almost a conversionary event, with artist after singer after rapper after poet electrifying the room with joy and beauty that clearly came out of painful encounters in the world. There, I heard the poet mai c. doan deliver her poem ‘New Diaspora’ with the concluding line, And when we pray, we pray into the mantle / we become our own prayer. There, I felt the deep joy of the undocumented singer Soultree as she sang of prayer in the Marshall Islands as a familial act. There, I listened to a poem about salsa dancing and was brought back to the dance floor with my wife.

It was far too facile for me to have labeled poetry, I reflected as I listened to Yu’s talk and over conversation with a group of people afterward, as an act of self-expression. The self, after all, is located in the world, and for Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, and indigenous peoples, that world has been orientalizing on the one hand and oriented toward the Pacific on the other. To make poetry is literally to engage in poesis, a word that I know in my Greek Catholic theological tradition as an act of shaping a work from the materials of the world. Indeed, while it is true that a number of people justify their secularity in relation to traditions like mine by admiring the poetry of our liturgy, the truer truth is that the stichera, tropars, kondaks, psalm readings, irmoi, and akathists are poems in the truest sense, shaping from the supernatural that is in the world that which we sing in an impossible attempt to speak of what we can barely grasp.

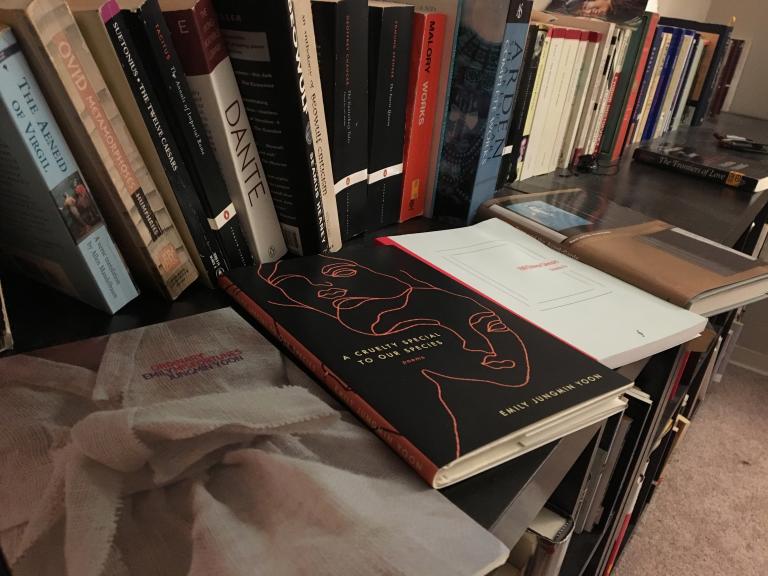

On the same note, I had the honour of meeting the poet Emily Jungmin Yoon that night and have now bought her books, where she gives voice to Korean diasporas, traumas, and networks, especially in her reflections on the disaster at Sewol in 2014 and redress for the trauma that ‘comfort women’ enslaved by the Japanese during their imperial conquest of Asia experienced. I learned that Yu’s interest in poetry was because he himself was a poet, and I listened to his exegeses of how two Korean American poets ‘disclaim America’ with almost a penitent sense that I was wrong to have written off this craft, as they are meditations on the truer truths of trans-Pacific Korean circuits. When I asked about whether this poetry directly addresses what I see as the neoconservative and evangelical turn in a number of our communities, they recommended that I read the poet Franny Choi, who writes about the terribly confusing events in 2015 and 2016 in Chinese America when our communities were divided between solidarity with Akai Gurley, a black man killed by the gunshot of a Chinese American rookie cop Peter Liang in what he thought was an empty stairwell, and support for Peter Liang, whom some took as a scapegoat.

I have always been slow to like Asian American literature, mostly because I also disdained that as a kind of empty self-expression, but as I reflected on these encounters with poetry, I thought of yet another talk that I recently attended by my colleague Michelle Huang, a dynamic English professor here at Northwestern. She spoke of two novels that situated the possibility of incarceration for Asian Americans in the present post-9/11 context like what happened to the Japanese in the Pacific War, and as I listened to her, it was clear to me that I had misjudged the situation. Prose, I know, is not poetry, but as genre is not my wheelhouse as a geographer, I wonder if something similar is going on here, that the arts of Asian America — as least the good bits — have seldom been about identity and have been about singing the world from the truths, even the darkest bits, about it. It is a little too simple to say that my tastes have been too centered on the ‘West’; there is no construct more ‘Western,’ after all, than the Pacific. It is perhaps better to say that looking at a world that I felt so deeply in my body and among those I lived requires a certain degree of emotional integration, and that process, as Audre Lorde points out for a number of straight men, has been long in bearing the beginnings of fruit for me.

What I notice my body doing as I have been reading, revisiting, and writing about this stuff in the last week or so is that I have felt like I am relaxing, slowing down as I engage. It is a little bit like a lengthy prayer service in our Kyivan tradition: to get through it, I have to throw myself into it, and in so doing, the beauty is there to meet me. My brother Sam Rocha has often tweeted that in order for academics to write — not just write well, but to write period — we have to assess whether we’ve had enough literature in our diet, and not just the academic literatures of our fields, but literature period. To write is to be literary, in any genre, and the reason for writing is to give voice to the world from the place where I am singing and seeing. I find myself increasingly having to admit that my life has been shaped by an experience of the trans-Pacific, of Hong Kong especially; it is no surprise, I think, that I have come back to the poetry of Asian American literature almost as a sacred art, but definitely secular in the end because it is about the space of the world. All poetry, perhaps, is secular in this liturgical sense, which means that – as I’ve been reflecting – liturgy is secular too, and the work requires that I give myself to this poesis, to this craft, to this slow act of reading and writing in the world. To me, this is why it is important that my career trajectory began with poetry. Terrible as what I produced then was, I wonder if that was how I simply sang the world then, and all I have been trying to do with the more that I write and produce is to try to see and hear it ever more clearly so that my craft becomes more deft and therefore truly creative.