Halfway into the film If Beale Street Could Talk, I said to myself: this is probably one of the most beautiful movies I’ve ever seen. It was, I thought, exactly what a Baldwin novel would look like on screen, the way he’d pace it, how he’d score it. My dear sister Grace Yu agreed, pointing out that it was also less intense that Barry Jenkins’s last film, the award-winning Moonlight. Of those among our friends, I’d say that Grace is among the more knowledgeable about films. I’ll defer to her judgment. I haven’t seen Moonlight, though now I think I will. Catholic though I may have become, I still sometimes fall back into the evangelical habit of claiming not to be caught up on the latest music and movies.

I have, however, read Baldwin. I used to say that I’d read everything he’d written, but then I saw I Am Not Your Negro two years ago and discovered that I have not even yet beheld the mountaintop. What is true is that the The Fire Next Time had a real effect on my career trajectory. I had read it in high school, and when the teacher assigned our class to write a poem as a response to it, I reached in desperation to the first vector of connection that I had with it: the Chinese church. Baldwin, after all, writes about the black church, in which my father was also ordained, so the link was more than metaphorical. The net result was that I felt for the first time that my own experience in the Chinese church was something that could be written about, that writing didn’t only have to take the form of fantasy novels, or the experience of Europeans, or scholarship on churches in anywhere but Asia. It was empowering to find that my everyday experience could be the source of literary reflection, and having run with it, I can trace the thread of my career now, in which I am rewriting my dissertation on Cantonese Protestant engagements with Pacific Rim civil societies into a monograph, back to that moment.

Womanist writers like Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and Maya Angelou have claimed, and Baldwin himself has acknowledged, that he was a spiritual father to them. I confess I probably have not read enough of them, and that is no fault of my education, as I encountered I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings at the Pentecostal elementary school, learned to read Genesis, Ruth, and Esther through The Color Purple in a course on the Bible as literature at the Catholic high school, and soaked in Morrison’s Jazz in my senior year there. It is more that these texts require an enormous amount of energy for me to read, and if that is evidence that Audre Lorde is right about me being a man-child who is unused to working on my emotional integration, then so be it. Following Lorde, the idea is that I’ll read them slowly, even if it takes me a lifetime for me to transform from a man into a person. Count it as part of my spiritual praxis, if not my further ascetic training in mystagogy. I started my catechumenate with The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill; I am sure that my education should continue to include the great womanist daughters of James Baldwin.

The basic argument in womanist theory, as I understand it, is that for all the rage about racializing colonialism undermining the manhood of men of color in the psychoanalytic terms of castration (though oftentimes literally, when it came to slavery and lynching), women of color, especially black women, suffer even more. Patriarchy is perverse in at least two senses here, and probably in more. The first is that in fighting for a kind of masculine dignity, the fate of women is tethered to men, which means that women suffer that much more when men screw it up, either by getting screwed over by the failure of their movements, or when they take out their screw-up on folks at home, or when they are killed or incarcerated and so on and so forth. The second is that this experienced phenomenon suggests that the liberation of men in the sense of overcoming castration and recovering agency is not the truest and freest state in which people of color can be. Patriarchy itself is revealed to be ideological. What this insight implies is that perhaps there is something even ontologically feminine, maternal, and womanist about the order of things as they are themselves, that anti-colonialism can only truly be as such when it unshackles the maternity of the earth.

Watching If Beale Street Could Talk reminded me that if I count myself among those who claim to be influenced by Baldwin, womanism is part of my tradition. Indeed, womanist phenomenology is, as Julian Hayda has long been developing the argument, is original to Kyivan practice, with our emphases on the Oranta as the Immovable Wall and the maternity of the black earth. The main character is Tish; the story is told from her perspective. Her man Fonny, whom she planned to marry, is in prison, falsely accused of committing a rape that he could not possibly have done. Tish is pregnant with Fonny’s baby.

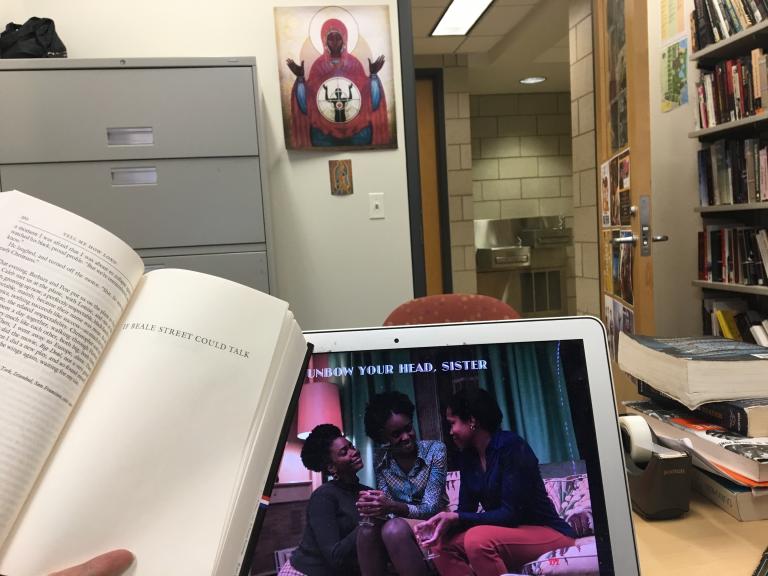

The crucial line that everyone talks about is delivered by Tish’s sister, simply named Sis for the purposes of the story. Upon finding out that Tish is pregnant, Tish’s mother Ernestine tactfully announces it to the rest of the family after dinner. She has her husband pour some old French brandy, and as they are drinking, she announces that they are drinking to new life, as Tish will have Fonny’s baby. They give her no stigma, but Tish feels it anyway. She was supposed to have been married to Fonny first, but she is pregnant anyway. She tries to explain it to her family. That is when Sis delivers the line. Unbow your head, sister.

That is womanism. Before the line is delivered — and this is much more so in the film than in the book, where the line is nestled at the end of a long paragraph — the beautiful, slow, and deliberate shots of the film feel fragmented. They are still beautiful, slow, and deliberate, but at least I was not really sure where the film was going. When Sis delivers the line, the direction of the movie snaps into place. The slow shots, the carefully considered angles, the contemplative soundtrack — they all serve to reveal what it means for Tish’s head to be unbowed, what empowerment true sisterhood can provide, what it means for Woman to be constitutive of reality. This is why the perversion of patriarchy is tragic. At the end — spoiler alert — when Tish’s mother goes to Puerto Rico to seek out Fonny’s accuser, it is when she touches the one she thinks could be her sister and daughter, placing her hands on the cross that the victim wears around her neck, that she begins to scream uncontrollably and the last ditch effort to set Fonny free goes awry. Womanism is both a celebration of life and the cry of the damned. The heads of the sisters are bowed, and only in unbowing them can the beauty of the world be revealed. The tragedy of Fonny is that in practicing his own dignity, all the women are dragged through no fault of anyone’s except the police state into his drama. The womanist argument is that hard as it is to avoid the trap of being pit against each other — impossible, even, as the end of the story shows — there is still something ontologically constitutive about sisterhood that is tied to how the beauty of the world is still seen and heard through Tish and that a world of love might be possible if men were not so damn fragile.

I left the cinema reflecting on the tragic beauty of If Beale Street Could Talk, often a hallmark of Baldwin’s writing now translated by Barry Jenkins into a sonic and visual experience that I felt matched the text. In so doing, I wished that I had had these words — unbow your head, sister — for so many students who come to my office hours, so many colleagues and friends who give voice to their struggle to me, so many times that I had failed to recognize the fragility of my manhood in the erotic presence of the ontological Woman. But oddly, I also felt that I had had them all along as part of an intellectual journey marked by Baldwin and his daughters, and I have been pondering how I might more consciously develop this praxis. Maybe the beginning is to slow down like the film, to see with jazz, to breathe with blues, and to craft with spirituals. Womanism, it turns out, is the furthest thing from ideology. It is seeing the world as it is, and simply from there, giving in to the deep impulse from within to fall in love, with all the tragic drama such an offering entails. You have trusted love all this way, Tish’s mother tells her, don’t give up now. I hear those words too with my heart and know, as Baldwin did, that my faith has never been misplaced.