To me, the theology of the Latin Church is encapsulated by the dictum, Ubi caritas et amor, Deus ibi est – where there is charity (agape) and desiring-love (eros), God is there. The rest of the song, usually sung by the Latins on Great and Holy Thursday, is, for lack of better words, about church politics – that is, about the church as a unique kind of polis, a civitas. Indeed, the next line gives it away – congregavit nos in unum Christi amor (gathered we in one by Christ’s desiring-love). There are exhortations against practices of schism: Ne nos mente dividamur, caveamus. Cessent iurgia maligna, cessent lites. (That our minds not be divided, beware. Let malignant urges cease, let litigiousness cease.) Instead, the church is built around the beatific vision, as the Latins have long called it, to see what the hesychasts in our Byzantine churches have called the Uncreated Light of Tabor and to be transformed from glory to glory. The Lord, as the Pentecostals put it, is enthroned on the praises of his people, and he is, in the words of the Evening Prokeimen for Great Vespers every Saturday, robed in majesty.

From my place in the Kyivan Church, I am happy to be in communion with this gathering of the people of God in charity and desire, though I am sure that such a claim will be contentious for more than one reason. Described in the terms of agape and eros, the Latin Church is not primarily an institution with a juridical culture that overemphasizes its universal jurisdiction, and therefore being in communion with Rome is not uniate in the sense that it comes out of a sense of inferiority to our sister church as some kind of ‘mother.’ Certainly, as this St Sylvester’s Day attests, the See of Rome was pivotal in establishing a symphonia between the church and empire. The Holy Bishop of Rome Sylvester was, after all, the Roman pontiff when the Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity and called the First Council of Nicaea. He was also known to be the pope under whom the Jews of Rome were removed from their homes, and St Sylvester’s Day is still laced with antisemitic undertones to this day. To celebrate the feast of St Sylvester today on the Old Calendar is a problem, and not because I am Orthodox (in communion with Rome); after all, St Sylvester even appears on the calendar of the Moscow Patriarchate, whose entire raison d’être for existing is to be anti-Rome as the Third Rome (lol). It is rather that it is as what my social justice-oriented students would describe it: problematic, and not in a productive way either.

Such institutional and imperial trappings, both the philosopher Ivan Illich and the Orthodox theologian Cyril Hovorun seem to agree, are not of the essence of what it means to be church. As Hovorun points out, the church as it was originally conceived was the gathering of the people of God in a local place, and it was only in trying to connect those localities that the concepts of hierarchy developed. The way that hierarchical institutions are imagined ecclesiologically, however, are extraneous to the beating heart of the church, which is found so beautifully articulated in the ubi caritas.

But I’d go further, and my sense is that Hovorun does too, which is probably why that one cranky Moscow Patriarchate bishop nominated him as the dark horse candidate, which did not come close to succeeding, to be the primate of the new Orthodox Church in Ukraine. It is not just that these imperial and hierarchical structures are extraneous to the church in its essence. It is that being in a church that wrestles deeply with our history with such infrastructure affords me a front-row seat to seeing the wasteland of its devastations. Recently, an Asian American evangelical friend of mine asked me how it was that I could have joined a Constantinian church, especially because I grew up in Chinese churches that emphasized the strict separation of church and state. After all, not only was I now in the Church of Kyiv, but it came by way of an eight-year detour through Anglicanism. I said it was simple. The empires that were supposed to be in symphonia with the church have all fallen: Constantinople, Kyiv, even Moscow. In fact, most imperial powers that were openly invested in the project of empire now don’t have them anymore, and in their place are all these zombie imperialisms, from United States hegemony to Putinist ideology and Xi Jinping Thought. I told my friend that it’s better, at least for me, to be in a church with an openly Constantinian past having to endure a world of zombie empire now than to be in churches that are so proud of being free from state control that they don’t know when they’re being controlled by neo-imperialism, which is basically true for all the churches of my youth now.

What does one do in a church with a front row seat to the zombie movie of Constantinianism? Some try to become the zombies themselves by trying to re-imagine neo-imperial and neo-monarchist ideologies, and I will confess that some of them are at least entertaining on the Internet, especially because all they’re good for is the blogosphere and Facebook rants, as opposed to real governance. A more serious task, though, would be to do real ecclesiology in such a world, to recover the vision of the ubi caritas amidst the ruins of imperialist institutionalism. It would be to cease our malignant impulses and litigious disputes because we have been congregated by Christ’s desiring-love, his amor, his eros, to join the women and men who behold the ineffable beauty of his countenance in the time that expands for sæcula per infinita sæculorum, for ages to infinite ages.

Sæcula per infinita sæculorum – the sæculum is that from which the term we know as secular is derived. In fact, John Milbank reminds us that before the secular was a space, it was a time, that which stretched from parousia to parousia, from Christ’s first coming to the second that will usher in the new heavens and new earth. There are, of course, a number of problems with Milbank’s theological project, not least of which includes his own British imperial nostalgia, but he stands in the long tradition of political theologians who have theorized that what is in fact responsible for the spatialization of the secular is the institutional bureaucratization of the Latin Church, especially in the tenth century Cluniac papal revolutions. Of course, some of Milbank’s neo-Anabaptist readers like Stanley Hauerwas follow the (very problematic) John Howard Yoder in going back all the way to the emergence of Constantinianism in the emergence of a church elided with the violence of a worldly political order. But the larger problem is that theology, if these theologians are to be taken seriously, now must be done in the shadow of empire, and even the Anabaptists, people-of-color, and indigenous theologians (who all disagree with each other too, often vehemently) are still working in a dialectical relationship with the imperial thread within Christianity. They are, I suppose, all problematic, but if there is anything that I know about myself, it is that I am drawn like a mosquito to the fire to problems. It is, as the all-too-problematic Slavoj Žižek reminds us, a form of erotic attraction to the beautiful flaw.

Far from implicating all of Christian theology as necessarily imperial, does not this insight instead lead to the more plausible possibility that theology itself has entered the fray of postsecular confusion? I am not a professional theologian — I am a social and cultural geographer who works on postsecular publics on the Pacific Rim — so I will not presume to speak for fields in which I have no stake, but as a practicing Christian in a post-imperial church, I must say that the strange thing about my own practice of theology is that I have to follow the ways in which the spheres of the ‘religious’ and the ‘secular,’ boundaries that betray the effects of secularization itself, are blurred. The dictum is not ubi ecclesia Deus ibi est, but ubi caritas et amor, where there is agape and eros. Beneath the devastations of the secular on the church in the world, there still exists the ontological reality to which the gathered people of God bear witness, and it is that the world is founded on love, in all the messiness of self-giving and desire.

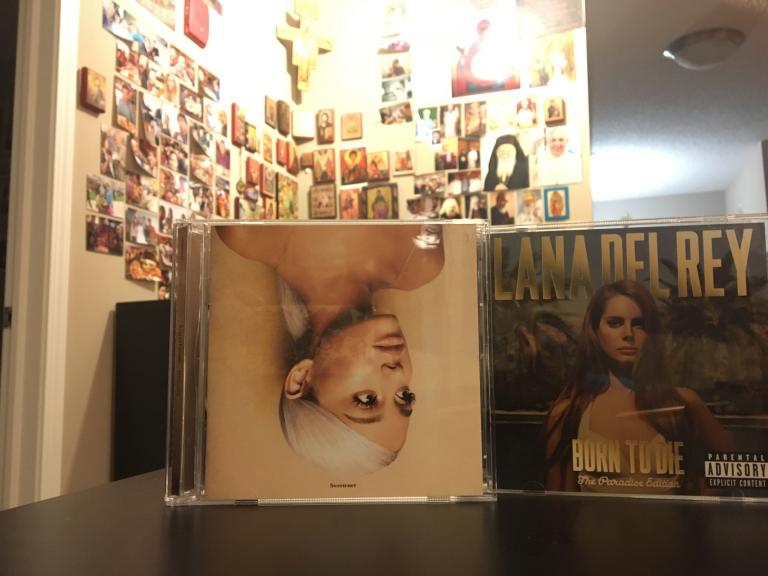

Earlier last summer, I wrote on how a group of friends I call my pop psychoanalysis posse have discovered in contemporary popular culture a thread that dances on the ruins of the theologically secular. Perhaps we are overly influenced by the Pop Art of Andy Warhol, an Eastern Catholic about whose practice of Eastern Catholicism I remain deeply suspicious, but we – especially Eugenia Geisel in her writing on Lipstick on my relics and Grace Yu in her musings on her American childhood – find in the thread from Madonna to Warholian pop stars like Lady Gaga, Lana Del Rey, Ariana Grande, Dua Lipa, Katy Perry, Taylor Swift, Brooke Fraser, and others a yearning for personal connection that is interrupted by the institutions that circumscribe their lives and the propaganda that is produced by them. I don’t want to steal either of my sisters’ thunder by saying too much, though what I will say is that it is not so much that these celebrities are in some way secretly religious or identify with our preferred forms of Christianity, but rather that they are, like Warhol, combing through the wasteland of the secular and making art out of the junk of their everyday lives. Often considered secular, these artists are sometimes rehabilitated by the church, as has happened to both Warhol and Gaga, and that is what drives my suspicions that such hagiographies are far too shallow. The church, after all, has been a progenitor of the secular as a space, and if these people are discovering agape and eros outside of it and speaking back to the devastations of secularization, perhaps theirs are voices and images to which I might pay better attention for my own praxis. I take heart, for example, that John Panteleimon Manoussakis seems to be thinking along the same lines too, especially in his work on Lars von Trier.

I suppose these musings on this St Sylvester’s Day serve as working reflections — what one of my editors called ‘pre-writing,’ which is the nature of the genre of the blog — for more of my professional work on the postsecular in relation to my practice of prayer. Certainly, writing it has helped me articulate my own draw to the problematic, that which is so full of problems that it threads through an extended intellectual treatment of a subject (orientalism, for example, is Edward Said’s ‘problematic,’ as he puts it, in the book of that same name), which perhaps helps me to reject the Puritan impulse in my evangelical upbringing to allow problems to paralyze my action for fear that it is not pure enough. Perhaps this is the beauty of being Catholic, especially in the Kyivan Church. It is problematic to be Eastern Catholic, I guess. But I am not scared of problems. I’d like to make art and scholarship of them. In this way, maybe Andy Warhol will eventually have something to do with my spirituality, though I really prefer his own philosophy to those who make an Eastern Catholic saint out of him when he probably wasn’t anything close to one.