I write these thoughts on the occasion of the Feast of the Annunciation on the New Calendar, in which kairotic time zone I am currently present.

During my flirtation with the Latin Church, I would pray the Angelus every noon. Or almost every noon. Maybe it was two or three days a week. Maybe less.

The point is that it was regular, at a time before I had encountered the Kyivan Church. I had learned about it like every Protestant learns about Catholicism — on the Internet — and the only way I knew, which was to watch videos of the pope, who was Benedict at the time. I learned quickly that the Bishop of Rome makes regular appearances at a window in the Vatican, and that was called the Angelus. It took a little longer to discover that the remarks weren’t the ‘Angelus,’ but the prayer, and that it is a devotion that can be prayed with or without the pope offering remarks at noon. I found it on Wikipedia and learned it. Later, I discovered these nuns singing it in Latin on YouTube with an Americanized accent and decided that if they could do it, so could I. To this day, I, as a Greek Catholic, can sing you the entire Angelus in Latin by muscle memory, including the final prayer. That means of course that I can do a rosary all in Latin too; it’s the same ‘Ave Maria’ between the Angelus verses, ten times, five times over (or fifteen, or you’re hardcare, and twenty if you’re at peak luminosity). When I say I don’t pray the rosary as a Greek Catholic, it doesn’t mean I don’t know how to do it. I did it for like seven years as an Anglican before I converted. It’s part of my muscle memory.

One of my favourite people to read, when I accepted that I was an Anglo-Catholic who was stuck in the world of evangelicalism (Anglican and otherwise — they’re both big tents, Anglicanism and evangelicalism), was Hans Urs von Balthasar. Balthasar is still one of my favourite people, but I’d say that my relationship with him is healthier now, less as a fanboy, more as a reader with rather the more ordinary reaction of humored incredulity to his verbosity. But one of the things that Balthasar always liked to talk about was the Annunciation, which is the point of the Angelus prayer, as well as the first of the Joyful Mysteries of the rosary. I know this because it’s on like the second or third page of one of his shorter books, Prayer (don’t ask me about his longer books). He really liked what Mary said when the archangel Gabriel told her she was pregnant, at what Balthasar calls the ‘first Hail Mary.’ Fiat mihi secundum verbum tuum, she replies, and of course it would be in Latin, because lol she’s Catholic. Let it be done to me according to your word.

Balthasar’s Annunciation spirituality, if one can call it that, was a revelation to me as a Protestant. It was what distinguished my Anglo-Catholicism from the rest of the evangelicals, who were aptly called with a classist sneer the low church. Growing up evangelical, I had always been taught to apply the Bible to my life. The Bible was, after all, the Word of God, and its verses should be studied for personal application, to hear it and do it and not be like the person criticized in James’s epistle for looking at themselves in the mirror and forgetting what they look like. Evangelical Anglicans loved this kind of thing too, especially those who took after their gurus like John Stott, J.I. Packer, and Harry Robinson (the latter two of which were locals in Vancouver, where I became Anglican, and where I came to know way too much information about the Communion). But after all I’d been through in falling off ordination track, I was tired. Balthasar swooped right in. Mary doesn’t apply the Word of God to her life, he said. The Word is applied to her.

I had no idea that this reading, taken in its strictest sense, lay at the heart of a Latin spirituality of docility — or worse, a kind of misogyny that is unfortunately endemic to Balthasar where he thinks of women as maternal nuptial figures because they kind of exist to receive seed from men (having seen Karen Kilby point this out, I can’t unsee it). In fact, as an evangelical justifying my Catholic leanings, I quite liked it. I often used it with my evangelical friends to tell them that Luther said the same thing in his reading of Paul’s letter to the Galatians. There, Luther distinguishes between active righteousness and passive righteousness. The former is a kind of salvation by works, where you do things to work for your own redemption. But Luther’s famous justification by faith alone requires the Christian to be passive, to simply lie there and take it from God, it being his pronouncement of righteousness by fiat. God issues his fiat, and Mary accepts the fiat: fiat mihi secundum verbum tuum. Balthasar and Luther, Mary and me: our Annunciation spirituality was passive, docile, accepting of the word instead of actively engaging it. I even wrote of this spirituality to a local Anglican priest who was trying to start a hipster parish in Vancouver with money from a Florida megachurch. He was, in my view, a bull in a china shop, and I wanted to get him to slow down. I probably should have just said that; there was no need to drag the Theotokos into it.

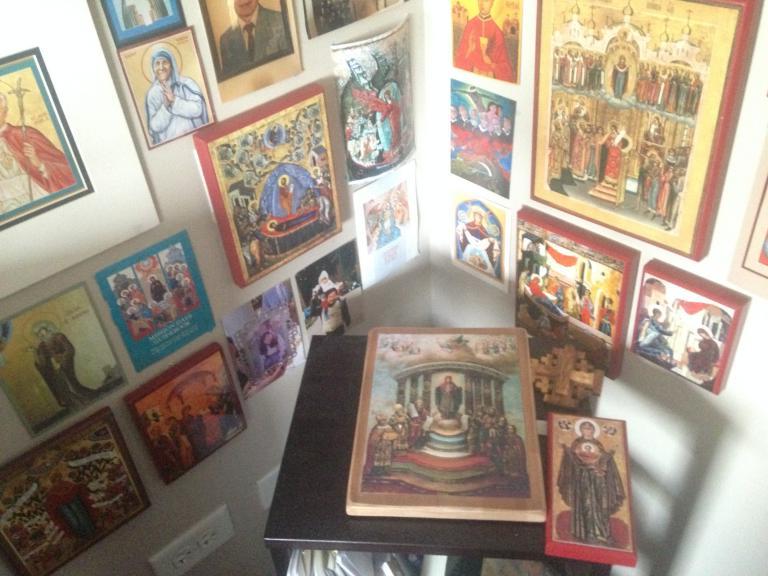

I honestly thought I’d get to keep this aspect of my spirituality when I became Greek Catholic, and for a while, I think I did. The Annunciation, after all, is painted on the Royal Doors of the iconostas of my home temple in Richmond. I recognized it right away when I first came to the temple, completely uninitiated, save my Internet searching. The Archangel Gabriel speaks to Mary; she responds. I still quite like the scene, which is how the icon has also ended up in my beautiful corner. But I can’t help but think that my caricatured Latin spirituality — and its caricature has a coherent explanation, which is that I acquired most of my knowledge of it from the Internet — was a kind of false humility, one that I believed was true because of my spiritual immaturity. The fruits of this exaggeration show themselves for what they are. From passivity, I descended into procrastination, and from there to a kind of non-engagement with the world. I thought that removing myself from the agon of the public arena put me above the fray. The people who were gathering around me had a similar attitude to life, which is to say that we indulged each other’s delusions of grandeur. While making career mistake after personal misstep, I began finding that the posture that looked humble was in fact a position of arrogance. It was the Anglo-Catholic trying to be the high church to the low church, a class move without the classiness, a fantasy of power at the end of the day.

The fatal flaw in this exaggerated Balthasarian interpretation of the Annunciation is that Mary is not passive. She asks the angel a question: How can this be, since I am a virgin? Reams of exegetical analysis have been produced on this inquiry, in fact, trying to differentiate it from her cousin’s husband Zechariah, who asks something similar in the temple and gets stricken mute by the same archangel. The fact is that there isn’t much that seems different, at least to me, in the text, in the same way that I can’t explain why G-d accepted Abel’s sacrifice over Cain’s. Whatever was the reason for the different outcome — or maybe there is no reason — it certainly was not Mary’s docility. Right after the Annunciation, she runs to her cousin Elizabeth and sings the Magnificat. Channeling words from Hannah, the mother of the Prophet Samuel, she turns full Miriam dancing in song after the people of God cross on dry land through the Sea of Reeds, declaring the liberation of the poor and the deliverance of the Lord of his people from oppression. It is no wonder that the first and third odes of the Matins canon — the first triad, if you will — contain the songs of Miriam and Hannah, building steadily through lessons from the prophets and the Three Holy Youths to find their culmination in the ninth ode in the Song of the Theotokos, the fulfillment of the prophetesses of old.

My spiritual father is known to stand at the Royal Doors and deliver what he calls sermonettes, short homilies on readings and sections of the liturgy, especially when there is a series of lessons. One time, he stood there and spoke of the Theotokos as the fulfillment of Miriam, the one who followed the baby Moses in his ark to the point when Pharaoh’s daughter drew him out of the water, the prophetess who joined her brothers in leading the people of God out of slavery through the Sea of Reeds and singing of the drowning of Pharaoh’s chariots — horse and rider he has thrown into the sea. Her name literally is Mary; that is Miriam.

In that moment, the icon at the royal doors showed me the scene anew. The Most Holy Theotokos, the fulfillment of the prophetesses of liberation, is not demurring to the angel; she is discerning the reality of which he speaks, that the Holy Spirit will overshadow her, the world itself is arced toward freedom and justice because it is constituted by what Henri de Lubac SJ calls le surnaturel, the very Spirit of God that continues to breathe as wind over creation. Fiat mihi secundum verbum tuum means that the world is suffused with the very presence of its Creator, and like the great Latin theologian Hildegard, the Theotokos is but a feather on the breath of God. This is not passive docility; it is active discernment, an engagement with the world as it actually is spiritually constituted, one that is pictured each time the Royal Doors are opened and the Annunciation gives way to the inbreaking of the kingdom who is Christ himself coming into our midst in the mysteries of wisdom, icon, and holy communion.

O Theotokos and Virgin, rejoice, Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee; blessed art thou among all women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, for thou hast borne the Saviour and Deliverer of our souls.