UPDATE: I wrote this reflection on St Clare two years ago, at the start of the Nun Wars. The Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR) and its head-butting with the Vatican are in the news again, and on the feast of St Clare it’s worth looking at (and praying for the intercession of) this singular woman religious who both challenged and obeyed the Church. At root, the word religious means “one who binds herself again.” To what—and to whom—do today’s women religious, sisters and nuns, bind themselves? Chiara—St Clare of Assisi—was a woman of strong ego and deep humility. If she were invited to speak to the LCWR’s annual conference this week, what might she say?

Upon a darkened night

the flame of love was burning in my breast

And by a lantern bright

I fled my house while all in quiet rest

Shrouded by the night

and by the secret stair I quickly fled

The veil concealed my eyes

while all within lay quiet as the dead

~ “The Dark Night of the Soul,” John of the Cross, adapted by Loreena McKennitt

After a week of wrangling over the role of women religious in the Church, it comes as blissful relief to celebrate the Feast of my favorite woman religious, St Clare of Assisi.

Her story is familiar, though often romanticized. Born in 1194 to a noble family of Assisi, Chiara Offreduccio was drawn to a life of prayer from an early age, perhaps inspired by her mother, Ortolana, a devout woman who had made all the major pilgrimages of the time—to the Holy Land, to Rome, and along the camino to the shrine of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. When a marriage was arranged for her at the customary age of 13, Clare asked for and received permission to postpone it until she was 18—but by that time it was too late. She had encountered the man who would become her literal soulmate, Francis of Assisi.

Clare, like many of the townspeople, had heard Francis preaching in the streets. Unlike many others, though, she was transformed by what she heard—the voice of Christ the Bridegroom calling her to leave her home and family to follow Him. In a scene out of a medieval romance (or even more aptly, a chaste retelling of the Song of Songs) Clare arranged to meet Francis at the church on Palm Sunday, on the pretense of receiving blessed palm branches. There he agreed to accept her religious profession. That night, under cover of darkness, Clare left her father’s house by the “secret stair,” the walled-off exit reserved for carrying away the dead. Francis himself cut her hair, and gave her a black robe and veil.

For a time Francis placed Clare with a group of Benedictine sisters, recognizing that there was no way a woman could join his small band of mendicant friars. Clare’s angry father brought armed soldiers to have her forcibly removed, but she prevailed on him with the strength of her convictions. Soon, Francis brought Clare to San Damiano, the small convent where his own vocation began. It was in the ruined chapel of San Damiano that Francis heard Christ speak to him from the cross, saying “Rebuild my church.” Francis did so, at first literally and later through his spirituality of radical poverty. At San Damiano, Clare was soon joined by other women (eventually, even her own sister and mother). They formed a new Franciscan community, known first as the Lesser Sisters or the Poor Ladies, now more familiarly as the Poor Clares.

Because of the social strictures of the time, Clare’s order was monastic and cloistered (though the sisters sometimes traveled to the Portiuncula and others Franciscan foundations to hear Francis preach). She wrote the Rule herself—the first religious rule composed by a woman. Over time, San Damiano became a haven of peace, a hive of honey-sweet prayer that sustained the whole Franciscan movement. When he was in deepest despair, believing his efforts lost, Francis retired to San Damiano to be borne up by the prayers of Clare and her sisters—and in that place, infused with a joy forged in the crucible of depression, he composed the Canticle of the Creatures, the first poem in the Italian language.

Because of the social strictures of the time, Clare’s order was monastic and cloistered (though the sisters sometimes traveled to the Portiuncula and others Franciscan foundations to hear Francis preach). She wrote the Rule herself—the first religious rule composed by a woman. Over time, San Damiano became a haven of peace, a hive of honey-sweet prayer that sustained the whole Franciscan movement. When he was in deepest despair, believing his efforts lost, Francis retired to San Damiano to be borne up by the prayers of Clare and her sisters—and in that place, infused with a joy forged in the crucible of depression, he composed the Canticle of the Creatures, the first poem in the Italian language.

Clare suffered from debilitating illnesses most of her life, but she persisted in the most ascetic practices of fasting and mortification. Ever practical and humane, however, she cautioned her sisters to be strict but temperate in their habits. To Blessed Agnes of Prague, a noblewoman who sought Clare’s spiritual direction about fasting, she wrote:

Because neither is our flesh the flesh of bronze, nor our strength the strength of stone, but instead, we are frail and prone to every bodily weakness, I am asking and begging in the Lord that you be restrained wisely, dearest one, and discreetly from the indiscreet and impossibly severe fasting that I know you have imposed upon yourself, so that living, you might profess the Lord, and might return to the Lord your reasonable worship and your sacrifice always seasoned with salt.

The Eucharist was the center of Clare’s spirituality. She is said to have turned away an army of the Holy Roman Emperor, bent on despoiling San Damiano and its nuns, by greeting them at the gates holding aloft a monstrance containing the Blessed Sacrament, which shone like a torch in her hands.

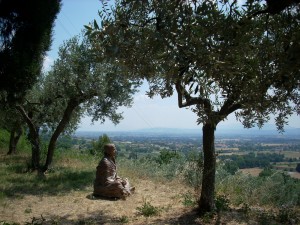

Chiara’s name means light, and her life sheds light on the questions we are still struggling with. Clare initially believed herself called, like the members of active communities today, to an active life, to walk the roads with the friars, calling people back to God’s love, living as the poorest of the poor in their midst. We don’t know whether she chafed at the demands of the cloister at first, but she was human, and it’s very possible. We do know she was surprised by grace to find, inside San Damiano’s walls, a whole world, a way of life joyfully embraced, a love beyond limits.

Chiara’s name means light, and her life sheds light on the questions we are still struggling with. Clare initially believed herself called, like the members of active communities today, to an active life, to walk the roads with the friars, calling people back to God’s love, living as the poorest of the poor in their midst. We don’t know whether she chafed at the demands of the cloister at first, but she was human, and it’s very possible. We do know she was surprised by grace to find, inside San Damiano’s walls, a whole world, a way of life joyfully embraced, a love beyond limits.

And we know that Clare, like many foundresses and superiors since, ran afoul of bishops and popes who were suspicious of a woman’s ability to lead a religious community, to write a Rule. They tried to revoke her Rule, claiming it was too rigid, and to lower her status in the order from abbess to prioress—the latter subject to the authority of an overseeing bishop, the former independent. To stifle Clare’s authority, a law was passed forbidding the adoption of “new” religious Rules—and backdated to the year before Clare wrote her Rule. She responded that her Rule was simply an adaptation of Francis’s Rule for the friars (which preceded the cutoff date) and therefore not “new” at all. She won her case.

Through it all, Clare lived her life rooted in humility and obedience to her call. She did not reject the authority of Rome; she engaged it in firm but respectful conversation, and the authority she claimed was in faithful service to the Gospel and the Church. On her deathbed she urged her sisters to listen to the counsel of the male Franciscan superiors, and never to allow outside voices to turn them from their absolute devotion to poverty.

The Church can be illuminated by the light of Chiara’s humility, I think, in the present conflict between the LCWR and the CDF and in many a dispute over who has the right-of-way on the camino of faith. St Clare is the patroness of television because, according to the collection of tales called The Flowers of St Francis, she was once prevented by illness from joining the other sisters at Christmas Mass with Francis and the friars. Alone at San Damiano, she was granted a vision of the events taking place at Our Lady of the Angels, projected on the wall of her cell in such detail that she amazed the sisters, on their return, with her account of the Mass. But charming legenda aside, Clare herself possessed tele-vision—literally, the ability to see far. And she focused that vision, from the time she first heard Francis speak, on the ultimate destination of all our lives, the life to come.

What a great laudable exchange:

to leave the things of time for those of eternity,

to choose the things of heaven for the goods of earth,

to receive the hundred-fold in place of one,

and to possess a blessed and eternal life.

As Clare died to her family, slipping out the secret stairway of death, so may we recognize that our journey only really begins when we die to self, to ego, to winning.

As Clare died to her family, slipping out the secret stairway of death, so may we recognize that our journey only really begins when we die to self, to ego, to winning.

May we turn our eyes and hearts, as Clare did, to the Eucharist, the utterly transformative wedding feast of Christ, without which there is no religious life and no life for the religious.

My we be strict with ourselves, and easy with those we love and lead.

May our lives be the place of solace and asylum where despair turns to joy.

May we never be afraid to engage in sincere dialogue with those who differ with us.

May we recognize the walls of the cloisters in which life places us, often against our will, as enclosing the very heart of peace, found only in surrender.

Santa Chiara, prega per noi!