For about a decade I understood that doubt and faith go together. That is to say, faith should be a questioning and critical self-reflective exercise rather than walking blindly in total trust. But I doubted everything. Faith was a fully intellectual exercise and very safe because it was an object. Faith didn’t require any self-examination. But it was also unsatisfying. There was an absence of hope that I could be part of something to transform my human condition to be better.

On the other hand, doubt was an exercise that allowed me to persist in the same state. This worked for a while but I became loaded with confusion. Doubt, as has been the case with many a thinker, was transformed into an agnostic boredom with faith.

What was I to do? The vicious absolutism on the fundamentalist right and the dogmatic liberalism on the left offered little more than masks of conformity to a social get together. Other communities seemed to be grasping at straws working hard to solve as many social problems as possible in the name of biblical justice. A worthy endeavor but I couldn’t recognize fulfillment to my deepest spiritual yearning. Religion seemed to ask questions that have no answers, and offer answers that have no questions.

Where was the mystery? That was the question. Paradoxically the answer offered no satisfying conclusion, yet neither did it require doubt. Faith in something mysterious is a consent to a living albeit incomprehensible reality. While I cannot actually change the world to suit my desires at the time, I can certainly change how I react to the world and alter my desires accordingly. Through the veil of mystery is where clarity found its home. The question is then where to find the guidance in order to make real contact with this mystery.

As Peter Rollins writes,

(W)hat if the church could be a place where we found a liturgical structure that would not treat God as a product that would make us whole but as the mystery that enables us to live abundantly in the midst of life’s difficulties. A place where we are invited to confront the reality of our humanity, not so that we will despair, but so that we will be free of the despair that already lurks within us, the despair that enslaves us, the despair that we refuse to acknowledge.

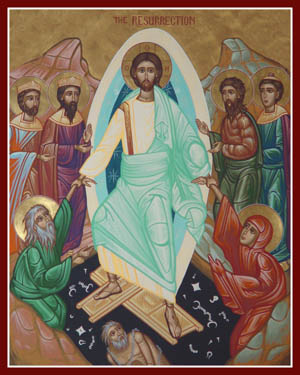

Exactly. What I found is that there has always been a place that observes such mysteries and practices this kind of liturgical structure. It is a place where the worship space and the world itself is a sacrament and there is no such thing as death. Death itself is something of an illusion because of the remarkable grace of God who destroyed it. Death isn’t part of the natural state of human being.

This place is where doubt is cast aside to trust in the thousands of pages of the saints before us who describe their rigorous practices and visceral encounters with God. Faith isn’t living in the world as-if it has significance but a consent to and a paradoxical fidelity to the mystery that makes it so.

In the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom during the period between Pascha (Easter) and Pentecost the Eastern Orthodox sing a Troparion particular to the Paschal season which is the sum of the very object of faith:

Christ is risen from the dead

Trampling down death by death

And upon those in the tombs

Bestowing life.

This is not a view of reality through the eyes of death and absence, but of a profound presence that has destroyed the bondage of death before we were even born. Sin is a sickness and death is its consequence – an unnatural state for which we require healing. Church is a hospital for the spiritually sick and offers the remedy for this common chronic illness through the Divine Liturgy.

This is what I wanted. I sought healing not moralism or judgment. It was in the incense and beauty of a space transformed into an icon of heaven in our midst. This space, this kind of progressive union with God that Christ’s resurrection made possible completely changed my worldview. It was and is participating in the eternal life of God and the saints who came before us and are still with us even now.

Christ died and rose from the dead to transform a dead humanity with life itself. I would much rather live in a reality where the tombs are empty because life itself emptied them rather than fill with self-pity and resentment because Jesus left us alone and in despair. It is through this life that we become part of the life of the Trinity itself.

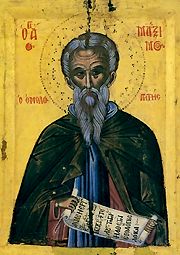

In the words of St. Maximos the Confessor:

For created things are not by nature able to accomplish deification, since they cannot grasp God. To bestow a consonant measure of deification on created beings is within the power of divine grace alone. Grace irradiates nature with a supernatural light and by the transcendence of its glory raises nature above its natural limits. – Philokalia, II, First Century of Various Texts, Sec. 76