Today most Christians know that Christianity is not Judaism. What separates a Christian from a Jew, among other things, is centrally the belief in the Trinity – one God in three persons. No good Jew, it is assumed, would believe that! It is also assumed by most that the belief in the Trinity, particularly the divinity of Jesus, was an unprecedented later development in the wake of the burgeoning church. If the confession of Jesus’ deity and its implications were early developments then that would have represented an early fundamental break from Judaism. Furthermore, it is assumed that even among early followers of Jesus, one can distinguish a Jewish form of belief from a Gentile Christian form by whether or not along with the belief in the Messiahship of Jesus there was also a confession of deity. Related to this of course is the supposed very early opposition between Pauline Christianity and Jewish Christianity.

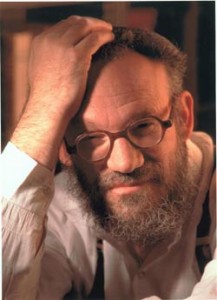

Daniel Boyarin takes on this conventional retelling of the Christian story and attempts to set the record straight in his new book The Jewish Gospels: The Story of the Jewish Christ. Boyarin wants his readers to see things “from that time” rather than “from our time with all the history that has intervened”. Here’s what Boyarin says in the opening paragraphs of his introduction:

Daniel Boyarin takes on this conventional retelling of the Christian story and attempts to set the record straight in his new book The Jewish Gospels: The Story of the Jewish Christ. Boyarin wants his readers to see things “from that time” rather than “from our time with all the history that has intervened”. Here’s what Boyarin says in the opening paragraphs of his introduction:

I’m going to tell a very different story, a story of a time when Jews and Christians were much more mixed up with each other than they are now, when there were many Jews who believed in something quite like the Father and the Son and even in something like the incarnation of the Son in the Messiah, and when followers of Jesus kept kosher as Jews, and accordingly a time in which the difference between Judaism and Christianity just didn’t exist as it does now.

While almost everyone, Christian and non-Christian, is happy enough to refer to Jesus, the human, as a Jew, I want to go a step beyond that. I wish us to see that Christ too–the divine Messiah–is a Jew. Christology, or the early ideas about Christ, is also a Jewish discourse and not–until much later–an anti-Jewish discourse at all. Many Israelites at the time of Jesus were expecting a Messiah who would be divine and come to earth in the form of a human. Thus the basic underlying thoughts from which both the Trinity and the incarnation grew are there in the very world into which Jesus was born and in which he was first written about in the Gospels of Mark and John (1-2).

The essential story Boyarin tells, which is a brief distillation of his detailed argument in Borderlines, is that before the fourth century what came to be called the Christian religion was not well defined in either belief or practice. In his terms, there was not yet a clearly defined “checklist” of who was “in” and who was “out”. During these first several generations after Jesus’ death and resurrection, there were a diversity of beliefs and practices associated with Jesus faith. It was not uncommon for example for a person to believe in the divinity of Messiah Jesus while maintaining close association with the life of Judaism, the practice of circumcision of sons, sabbath observance, dietary restrictions, etc. While there were those who opposed such mingling of Jewish practice and belief in what came to be known as orthodox Christian faith, these were not hermetically sealed categories.

Boyarin believes that the consequence of the Ecumenical Councils of Nicaea (318) and Constantinople (381) was to separate Judaism and Christianity completely. What’s more with the backing of the Empire these distinctions could now for the first time been enforced by law. As Boyarin puts it

Before that, no one, (except God, of course) had the authority to tell folks that they were or were not Jewish or Christian, and many had chosen to be both. At the time of Jesus, all who followed Jesus–and even those who believed that he was God–were Jews . . . Nicaea effectively created what we now understand to be Christianity, and oddly enough, what we now understand as Judaism as well (14).

The church father Jerome captures this decisive division perhaps best when he says of Christian Jews, “But while they desire to be both Jews and Christians, they are neither the one nor the other” (quoted on pg 16).

Boyarin calls for a new way of thinking about the varieties of Jewish religious experience that would all both the burgeoning Rabbinic movement as well as Christian Jews to be seen as historically expressions of ancient Judaism. He suggests that a better image for the period in place of the checklist, since it ends up excluding arbitrarily segments of the people that are in both lists (Jewish and Christian), is that of family resemblance. Family resemblances as an image captures the fluidity of the period. A family resemblance means that members of a family share features, but no one feature is shared by all members. There are a cluster of features of which individual members might share. Of course to be a Christian there must include a form of discipleship around Jesus. But this alone would not make one unJewish. What’s more, while two Jews may disagree on Jesus, they may at the same time share a number of other features. Discipleship around Jesus does not disqualify one from Jewish identity, although it would disqualify one from being a Christian Jew. The model of family resemblance, then, may be an apt, and more historically sensitive, way of talking about a Judaism that incorporates early Christianity.