I continue to struggle with how to factor in the plurality of the four Gospels when presenting the story of Jesus. On the one hand, I am uncomfortable with the harmonizing and minimizing tendencies of my evangelical tradition when it comes to alleged contradictions in detail. Francis Watson I think is right when he recently wrote about alleged contradictions among the four Gospels:

I continue to struggle with how to factor in the plurality of the four Gospels when presenting the story of Jesus. On the one hand, I am uncomfortable with the harmonizing and minimizing tendencies of my evangelical tradition when it comes to alleged contradictions in detail. Francis Watson I think is right when he recently wrote about alleged contradictions among the four Gospels:

There are very many of them, and they often relate to issues at the heart of Christian faith and life. More importantly, to trivialize the alleged contradictions is also to trivialize the differences that constitute the individual gospels in their discrete identities. The problem of alleged contradictions can only be resolved by recognizing that the criterion of correspondence to factual occurrence is already rejected in the canonical form itself. As Origen recognized but Augustine did not, the apparent contradiction demonstrates the inadequacy of this criterion and compels the reader to seek the truth on a different plane to that of sheer factuality (Gospel Writing, 14, emphasis added).

On the other hand, I am nearly a complete skeptic when it comes to the tools for establishing historical authenticity. Even recently, I read the discussion of historical Jesus scholars and continue to be troubled by the flimsy methodology and so the usefulness of the entire endeavor. There are improvements being made on the method, particularly in the recent work of folks like Anthony LeDonne and others drawing on the recent work on memory in the social and cognitive sciences along with the rejection of positivistic historiography with its quest for “what really happened”. But it remains the case that the so called historical Jesus will be remote to us no matter the methodological improvements. What’s more, Martin Kähler’s claim continues to be true that “a so called historical Jesus” – stripped as he is from his canonical particularities – is not a Jesus which births and sustains faith. The Jesus of Christian faith is the Jesus of the four gospels in all their particularity, their story structures, their renditions of Jesus’ sayings, their settings, plot and characters. And, as Kähler claimed, so do I: the real historical Christ is the Jesus who is preached.

There must be a third way that rejects the Jesus of the Harmony on the one side and the Jesus of historical criteria on the other; one that nevertheless remains historical, theological and biblical. Has anyone figured that out that path?

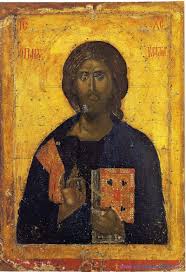

I’m sympathetic to Martin Kähler’s provocative, rhetorical question: “Is it really a deficiency when the origins of this image [the Jesus of the four gospels] remain shrouded in obscurity?”

It seems that Watson is attempting to lay a foundation for a third way in his book Gospel Writing. Here is an insightful exerpt that gets at the heart of the matter, and points to the positive, rather than negative, value of gospel difference one the one hand, and, on the other, names the fourfold canonical “gospel” as the final one story of the gospel:

The fourfold retelling of Jesus’ story complicates the relationship between that story and empirical historical reality. Within its new fourfold context, the individual gospel’s claim to retrace the exact course of historical events proves hard to sustain: when one gospel tells how Jesus preformed a certain action as he approached Jericho, its claim is thrown into question when another gospel states that he performed this action on leaving Jericho. Innumerable small-scale divergences such as this together constitute the irreducible difference that establishes the gospel’s plurality; without them there would not be four gospels but four copies of a single gospel. An indirect relationship to empirical occurrence and sequence is therefore integral to the fourfold canonical narrative. Like metaphor, narrative can further the communication of elusive truth precisely as its literal-historical sense is suspended; the event of the Word made flesh cannot be adequately communicated by conventional historical method. Yet plurality is also a feature of normal historiography, however much an individual historian may strive to monopolize his or her subject matter. The glossing of ευαγγελιον as ευαγγελιον κατα . . . acknowledges the perspectival nature of all history writing. Where difference is seen as a problem or weakness that calls for elaborate harmonization procedures or critical unmasking, the root cause is a dissatisfaction with canonical pluralism as such and a determination to reduce it to singularity. But that is to overlook the hermeneutical significance of the canon itself, which strives to integrate the voice of the individual witness into an encompassing polyphony (615-16)