Aug. 28, marks 61 years since Martin Luther King, Jr. stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and announced to the world that he had a dream. Today, King’s dream is far from a reality.

King was having a significant 1963.

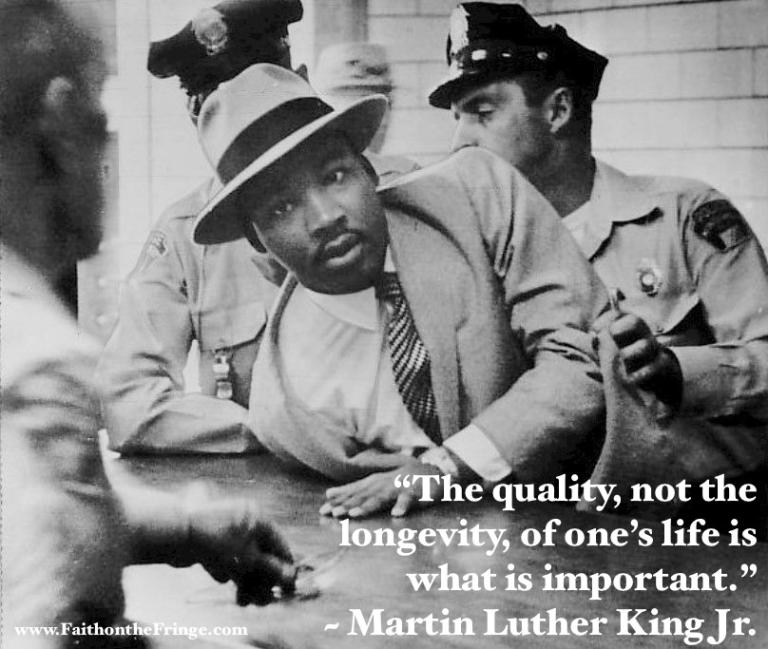

That spring, King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference led demonstrations and economic boycotts in Birmingham, Ala., where the local law enforcement was notoriously anti-integration and the state’s white supremacist governor declared in his inaugural address, “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!”

Throughout the first few weeks of April, night after night, in church after church, King preached nonviolence to a growing following of volunteers.

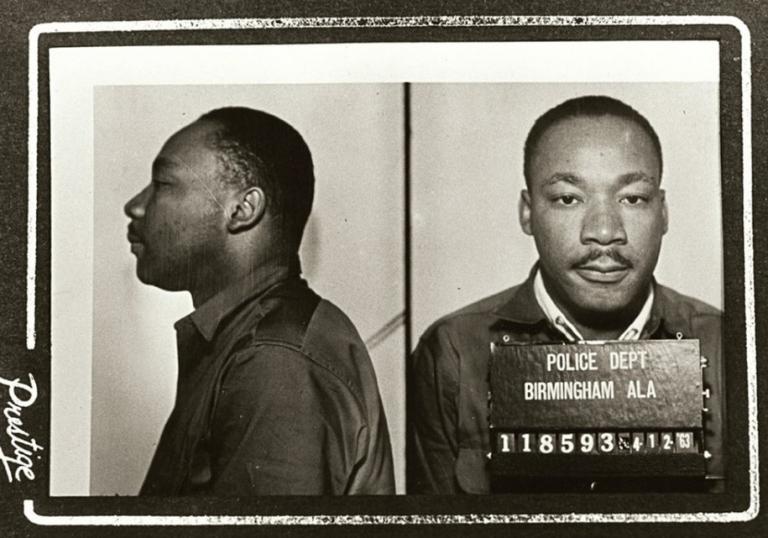

Peaceful protesters were arrested daily. In violating a court order, King offered himself up for arrest on April 12, Good Friday.

Held incommunicado for more that 24 hours, King was permitted no visitors. It was only after the personal intervention of President Kennedy and Attorney General Bobby Kennedy, was King allowed to speak to his wife by telephone Sunday afternoon.

On the day of his arrest, eight white Alabama clergymen published a letter in a Birmingham newspaper calling for the boycott and protests to cease, for Negroes to be more patient, and praising the police for their calm during the demonstrations.

“Letter From Birmingham Jail”

Alone in a filthy jail cell, King read the letter and immediately began drafting a response on the newspaper itself. He eventually composed a landmark epistle that addressed their concerns, clearly defined the civil rights movement, touched on far-reaching philosophical questions, and served as an inspiration for generations of the oppressed around the world.

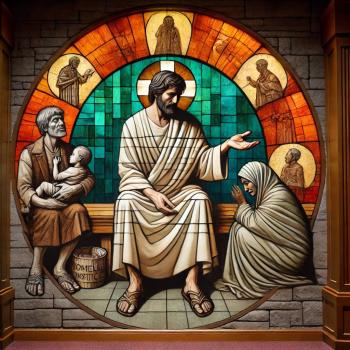

“How does one determine whether a law is just or unjust? A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. . . . So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists will we be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice? In that dramatic scene on Calvary’s hill three men were crucified. We must never forget that all three were crucified for the same crime – the crime of extremism. Two were extremists for immorality, and thus fell below their environment. The other, Jesus Christ, was an extremist for love, truth, and goodness, and thereby rose above his environment.”

While King’s letter seemed to fall on deaf ears at the time, one modern historian described it as “the most splendid and elucidating prose that King ever wrote. Decades later, it is studied all over the world by those interested in nonviolent struggle.”

As more protesters joined the non-violent effort in Birmingham, police responded with increased violence. Images of unarmed, peaceful demonstrators, many of them school children, attacked by police dogs and fire hoses, were broadcast around the world, and helped sway a public previously blind to the violent enforcement of segregation.

In Washington D.C., President John Kennedy and his brother Attorney General Bobby Kennedy watched news reports of peaceful demonstrators violently attacked by the police.

Deciding the time had come to add his voice to the civil rights struggle, President Kennedy addressed the nation from the Oval Office on June 11.

Utilizing a King-like justification of law and God, Kennedy told a national television audience that “we are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution. The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities. . . Next week I shall ask the Congress of the United States to act, to make a commitment it has not fully made in this century to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law.”

King’s non-violent attack on racism and segregation in Alabama led a presidential assault on racism across the country. Kennedy’s civil rights legislation ensured the right to vote, and eliminated discrimination in all public places, including hotels, restaurants, and retail establishments. He also proposed expanding the attorney general’s power to enforce court-ordered school desegregation.

By the summer, the proposed legislation stalled in Congress, with Southern segregationists blocking key aspects of the legislation.

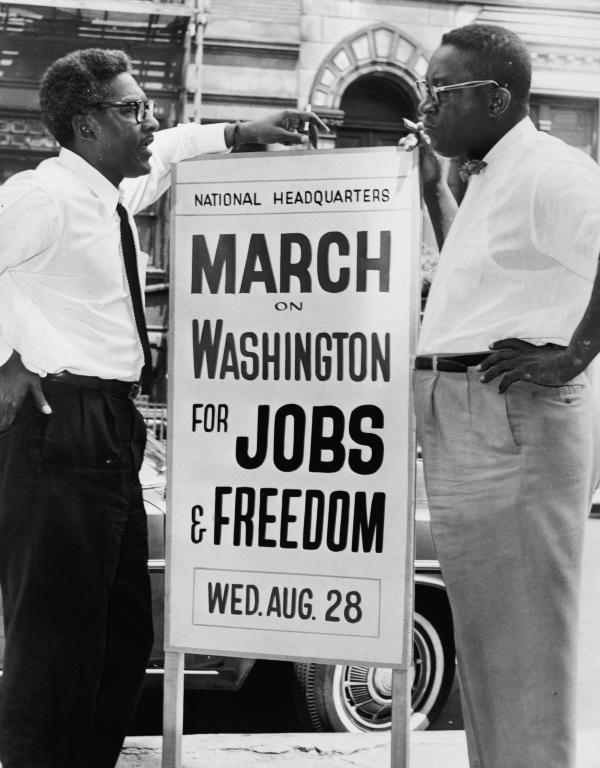

Black leaders proposed a march on Washington to unite the civil rights movement, and to demonstrate to Congress their dedication. While initially opposing the march, sensing the inevitability of the rally, the Kennedy’s worked to ensure its success.

They helped arrange participation of white churches and labor unions and assisted with a myriad of logistical and law enforcement issues. More than 250,000 people assembled on Aug. 28, 1963.

“I Have a Dream”

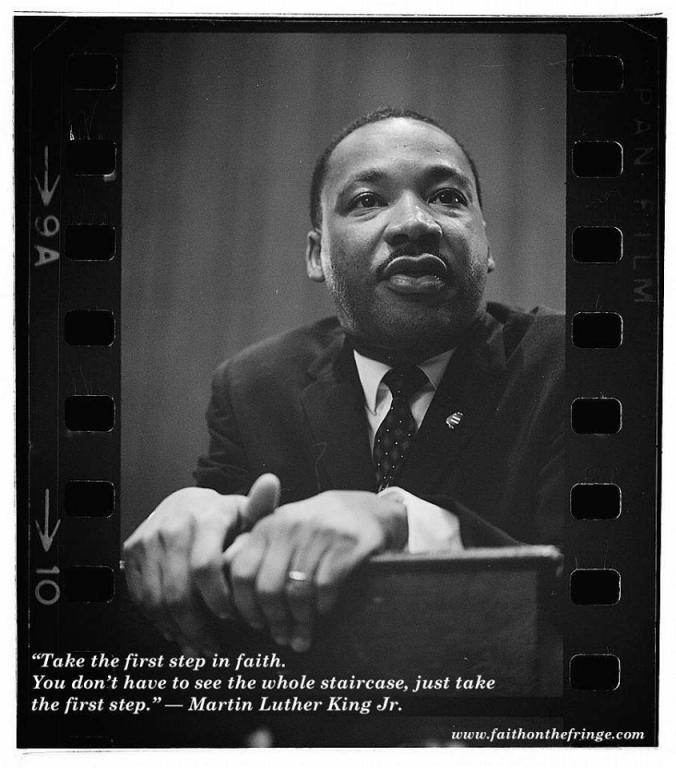

King stayed up most of the night before working on his speech, but he hadn’t planned to use the iconic phrase in his prepared remarks. Drawing on previous writings and speeches, King laid out the justification for the struggle and why the time was right for change. But when he came to the famous section about his dream that “one day, this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning if its creed,” he moved off of his prepared text, and stepped into the role of America’s preacher.

Repeating the familiar refrain, “I have a dream today,” King effortlessly shifted from describing Southern racists, to quoting Isaiah 40:3-5, and the voice of one crying in the wilderness:

“I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain and the crooked places will be made straight and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.”

(For excellent audio of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, click here)

The year of civil rights was punctuated in September with the death of four young black girls, killed in a Birmingham church bombing, and again two months later with three shots in Dallas.

The nation’s suffering was cauterized and Kennedy’s legacy secure with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Today, King’s dream remains far from a reality for too many black and brown Americans.

Too much money is spent on the for-profit prison industry and not enough on education. Hundreds of black Americans continue to die every year while in police custody. Black Americans are nearly three times more likely to be killed by police than white Americans.

Too many of us are still waiting for King’s dream to become a reality. We wait for justice and equality to be extended to all Americans, not just certain groups.

We wait, and another year passes.

Follow these links for other Civil Rights posts:

Remembering Civil Rights Activist Jonathan Daniels

The Civil Rights Struggle Continues, so Others May be Free

The Clark Doll Study Documenting the Damage of Segregation

Martin Luther King. Jr. and the Original Black Lives Matter Movement

Ω

Pastor Jim Meisner, Jr. earned his M.Div. from the oldest HBCU seminary in the United States. He’s the author of the novel Faith, Hope, and Baseball, available on Amazon, or follow this link to order an autographed copy. He created and manages the Facebook page Faith on the Fringe.