Like thousands of other X Users, I recently deactivated my X/Twitter account, migrating to Threads, and then to Bluesky, to get my social media fix. This weekend, NBC reported that many journalists are quitting X as well, especially after X owner Elon Musk admitted to deprioritizing posts that included links, thereby limiting the ability of reporters to reach readers seeking more than a sound bite of information offered by Tweets.

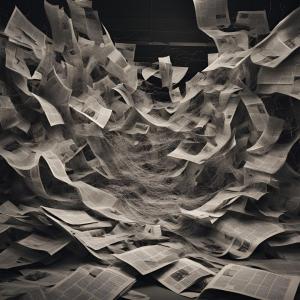

And herein resides a significant problem: too many of us are relying on sound bites—Tweets and TikToks and AI-Generated Facebook posts—to get our news. Satiated primarily by the immediacy of “news” and the dopamine hit these platforms provide, we are no longer willing to sit with information for more than a moment or two, lacking the patience and the persistence to seek and share the truth.

It’s far easier to repost a salacious story and watch the likes come in with fingers crossed, hoping that the rumors just happen to be true. Or not true, actually, because it’s not the truth that’s at a premium: just a tidbit that will confirm our biases, stoke more divisions, make us even more suspicious of our neighbors and coworkers and friends.

Who has time to fact check anything anyway? Do we even care about the truth anymore?

The Necessity of Fighting Disinformation

I’ve been thinking a great deal about disinformation this fall, in part because I teach journalism courses to undergraduate students—young people who are part of the social media ecosystem, but also have a deep desire to know and report truth. I’ve also been thinking about disinformation in light of an election that seemed in part driven by the kind of false news that put people’s lives at risk: from immigrants accused of eating people’s pets, to hurricane disaster relief being funneled to immigrants, to what seemed objectively absurd claims about Democrats drinking children’s blood.

As people of faith committed to Truth, it seems like Christians would reject disinformation and its proliferation. Yet, as early as 2020, Sojourners Magazine was reporting that disinformation networks see religious groups, most notably evangelical Christians, as ready targets for their campaigns to spread conspiracy theories and discord. In the years since that reporting, several books have explored the role Christians play in promoting fake news—and what they can do to stop its spread; this includes the excellent collection, Q-Anon, Chaos, and the Cross, edited by Michael W. Austin and Gregory Bock.

At George Fox University, we are using first-year writing classes as one place to combat the spread of disinformation, hoping to give students the tools they need to interrogate the social media posts they encounter for truth, rather than succumbing to a far more common impulse: to believe only the information that confirms their biases; to share “news” that stokes division and chaos; and to move on quickly to the next post or video, rather than taking time to consider what it means to seek and know truth.

The Necessary Tools for Fighting Disinformation

In our first-year writing courses, we teach students to use the “Four Moves of Web Literacy” introduced in Michael Caufield’s e-book, Web Literacy For Student Fact Checkers. These four steps can be instructive for any reader committed to stopping the spread of information, and include

- Check for previous work: Looking at other fact-checking sites, like Snopes or FactCheck.org, might help decipher whether the story is true or not.

- Go upstream to the source: Finding the original source for a report, if such exists, can help readers see whether a fact has been distorted by others.

- Read Laterally: Seeing what other people have reported about an original source provides perspective, and offers a way to check one report against others.

- Circle Back: Reaching a cul-de-sac or going down rabbit holes might move readers away from essential facts; in those cases, circling back to what is known to be true provides a foundation from which to search more.

Students in our first-year writing classes are required to apply these steps to a news story considered polarizing, deciding whether the news story presents disinformation, and whether the language used by the reporter is designed to stoke strong emotions, seeding division and chaos. By the end of the unit, and the conclusion of their essays, we hope that students will have the tools necessary to combat disinformation where they find it.

The Necessity of Patience in Fighting Disinformation

Of course, fighting disinformation takes time and patience. Because our general education curriculum is virtue-based, our first-year writing course also examines the virtue of patience, how it applies to the writing process, and how it helps shape our search for truth—or, how the lack of patience, deforms that search, too.

Fighting disinformation will take a lot more effort than deactivating X/Twitter, and cannot be accomplished alone. But people of faith can commit to the virtue of patience when it comes to reading, responding to, and spreading the news. It seems like this is one place where Christians—those folks who are followers of The Truth, The Way, and The Light—could have significant influence, especially in an environment where chaos and division continue to reign.