Like so many others in my community and elsewhere, I’ve been spinning out with anxiety about the state of our country. Each day’s news cycle brings more chaos and uncertainty and rage-inducing headlines. For the first week (or so) of a new presidency, I was doing okay, holding on to hope, certain that the country’s guardrails would hold, if only barely.

But then came the plane crash in Washington, D.C., and President Trump’s inference that women and minorities were to blame for the tragedy; the scrubbing of any DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) language on government websites, and the announcement that the government would not honor Black History Month; and tariffs levelled at Mexico and Canada, now paused for 30 days, necessary because (apparently) of immigrants, who have been an easy scapegoat for every impetuous decision by the new administration; and Elon Musk’s unlawful takeover of the national security and treasury systems.

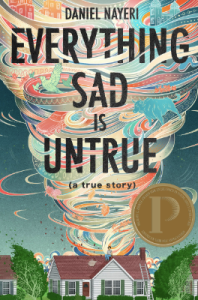

The anti-immigrant rhetoric was in full swing last October when I chose my texts for my spring classes, including Daniel Nayeri’s Everything Sad is Untrue: A True Story. The memoir narrates Nayeri’s experience as a middle schooler living in Oklahoma as a newly arrived refugee from Iran. Now, reading it with my first-year writing students (at least those who are reading along), the book feels especially prescient.

Daniel (his Iranian name is Khosrou), the narrator, is a twelve-year-old boy who begs to be understood by a middle school classroom full of bullies, and by his readers. The story he tells, in part about his family’s pain and suffering, is emblematic of so many other immigrants who long for security and safety, and whose landing in the United States is met with discrimination and abuse.

Listening to the Refugee’s Story

On the book’s very first page, Daniel says this: “If you listen, I’ll tell you a story. We can know and be known to each other, and then we’re not enemies anymore.” I underlined that passage, earmarked the page, read it to my first-year writers, then emphasized it in several subsequent classes and conversations. His is an affirmation for our times, for our inability to listen and empathize. (One prominent Christian publisher is even busy promoting a book called “Toxic Empathy.”)

So few of us listen to each other’s stories anymore, choosing instead hostility, and bullying, and scapegoating. Choosing to be enemies, because somehow that’s easier, more satisfying. Acting much like the middle schoolers in Daniel’s classroom, even.

Everything Sad is Untrue uses Persian mythology, family legends, and Daniel’s memories to narrate the journey his family takes to arrive in Oklahoma. Nayeri affirms that most immigrants come to the United States for reasons we should find admirable rather than deplorable; and that, were others in a similar situation, trying to protect their children, they would probably make similar decisions.

Everything Sad is Untrue shows how refugees are mistreated and maligned by the communities where they settle, but also by powerful forces that cause them to escape persecution, as well as systems that dehumanize and debase them in the name of providing aid. And also, Everything Sad is Untrue is also about a middle schooler who, like everyone else, just wants to belong, to know that he is worthy of respect and love—a reminder that immigrants are, fundamentally, human, with human emotions and longing.

God’s Mercy and Love for All, Including Refugees

Ultimately, Nayeri’s book is about God’s mercy for us all. The narrative arc in this book bends toward justice and love, just as it does for the universe; and someday, even if it takes “a thousand years,” according to the narrator, we will be made whole despite the heartache we encounter daily.

This is such an important message in this place and time, for my students, for me. Most days, I feel absolutely demolished by the human cruelty that exists around me, the bullies who make people like Daniel Nayeri’s life miserable. Tapping into social media has a tendency to amplify my despair, as my feeds highlight the abject horror of people with power and money, exacting a perverted kind of revenge on others. Bullies writ large, in other words.

As I’m writing this, President Trump is signing an executive order to begin the process of dismantling the Department of Education, which will undermine the country’s educational system and harm our children’s ability to learn and to understand the world beyond their small lives. In an era when fewer and fewer people are reading books, when our attention spans are shorter, when books have been deemed tools for indoctrination, reading seems like it can serve one form of resistance to despair and to the dehumanization of those, like immigrants, who have a story to tell.

As I’m editing this and getting ready to post, President Trump signaled that he wants to remove all Palestinians from Gaza, and that the United States could take over the land for beach resorts and a new “Middle East Riviera.” His proclamation will definitely cause more human suffering, even if it never comes to pass. Once again, victims to the whims of the powerful lose nearly everything, even the human right to exist on their own land.

I know that there is other work to be done, and other far more potent forms of resistance. For now, though, I plan to be downright evangelical about Nayeri’s book and about the power of reading, in my classroom, in every conversation I have, with the hope that our country’s narrative will bend back toward justice, and that doing so won’t take one thousand years.