What place does ambition have in the life of a Christian? In Shakespeare’s play Hamlet, the main character struggles with his own desire to become king. He has to reflect on the nature of his deep emotional draw to the crown and his advisor, Rosencrantz tells him that “the very substance of the ambitious is merely the shadow of a dream” (Guildenstern in William Shakespeare’s Hamlet). The tragedy of young Hamlet shows that ill-advised ambition can lead to ruin. Yet, without ambition, would the dreams that may come ever achieve fruition?

Nature of Ambition

Ambition might be defined as a striving for some kind of achievement or distinction, and involves, first, the desire for such, and, second, the willingness to work towards it even in the face of adversity or failure (Neel Burton, “Is Ambition Good or Bad?”).

In the Gospel (Mk. 9:30-37), the evangelist Mark shows the disciples debating who is the first among them. Jesus speaks to them, and they feel immediately reproved. Jesus suggests that aiming to be the first among the disciples is not a worthy goal for their aspirations. From the beginning of the Western canon of literature, we often see ambition portrayed as something evil. This comes out clearly again in the case of Hamlet.

Plato’s Problem with Politics

Already the ancient Greeks saw the possible dangers of ambition when it was merely a desire for power.

In the Republic, Plato says that, because they are devoid of ambition, good people shun politics, leaving us to be ruled by bad people and their petty ambitions. Even if invited, good people would refuse to rule, preferring instead to hide in their libraries and gardens. To force them out, Plato goes so far as to advocate a penalty for refusing to rule (Neel Burton, “Is Ambition Good or Bad?”).

Distinct Types

Plato’s contemporary Aristotle, on the other hand, takes a more nuanced position and distinguishes between healthy ambition, unhealthy ambition, and lack of ambition. While we all know people who lack ambition and are stuck in life, their state of life does not seem like something we should desire, and it is not overly common to find ourselves in this state. Instead, we are much more likely to be stuck in a hard place between healthy and unhealthy ambition. I have known doctors who begin their studies with a wonderful ambition to help make the world a better place. Yet, their studies and their networks force them into a position of doing things that they find morally questionable. They are shuttled into a world of ambition that ends up sucking the life out of their souls.

It is also common for the world of politics to give way to selfish ambition. St. James warns us that

Where jealousy and selfish ambition exist, there is disorder and every foul practice (Jas. 3:16).

This is part of the tragedy of Hamlet’s character, who is willing to sacrifice virtue for his own gain.

Evil of Jealousy

We notice these dynamics in many of our relationships and see how much jealousy is capable of destroying. It would be a mistake to respond by concluding that we should get rid of all ambition or aspiration. Rather, we should work to purify our intentions and make sure that we frequently check ourselves and the motivations which propel our actions.

Sensitivity to Failure

When we are highly ambitious, we are more sensitive to failure. Here is where the Christian virtue of humility can help us greatly. Selfish ambition leads to justifying unsavory behaviors. We allow ourselves to “color outside the lines” as long as we are achieving our goals. Humility, however, allows us to fail in our goals yet realize that we are not ourselves failures as long as we are virtuously continuing the process of becoming the men and women that God wants us to be. When we are humble, we never face absolute failure because we recognize that we are ultimately in God’s hands.

The way of humility is not the way of renunciation but that of courage. It is not the result of a defeat but the result of a victory of love over selfishness and of grace over sin (Pope Benedict XVI, 2 September 2007).

Nietzsche’s Criticism of Humility

Nietzsche criticized the Christian virtue of humility because he thought it was a surrender to weakness.

To Friedrich Nietzsche, humility was a great barrier against humanity’s progress. He saw humility as a self-protective instinct by the weak, poor, and powerless. Since these less fortunate individuals cannot attain the power and resources needed to obtain happiness, they twist their powerlessness into a virtue and proclaim it as a desired end in itself. In this way, the weak try to stymie the strivings of the strong by proclaiming that humility, not power, should be the desired goal. When cast as a virtue, argued Nietzsche, humility keeps those who are capable (i.e., the strong and powerful) from reaching the fullness of their potential (Bollinger and Hill, “Humility”).

We can find echoes of this in our own worldview. However, in Christ, we find someone who vanquished the world precisely through the strength of humility. Nietzsche reduces humility to subservience, but in the Christian view it is the clearest show of strength and courage.

Holy Ambition

We should learn to be ambitious about holy endeavors. St. Francis de Sales spoke about this in a letter to a young man.

It is said that Alexander the Great, sailing on the wide ocean, discovered, alone and first, Arabia Felix, by the scent of its aromatic trees. He was at first the only one to perceive it, because he alone was seeking it. Those who are seeking after the eternal country, though sailing on the high sea of the affairs of this world, have a certain presentiment of heaven, which animates and encourages them marvellously. But they must keep themselves before the wind, and their prow turned in the proper direction (St. Francis de Sales, Letters to Persons in the World, p. 213).

Choice Between Christ and the World

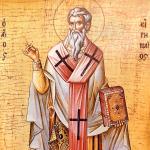

We have a clear choice between the way of Christ and the way of the world. We can choose to live humbly or to be carried away by selfish ambition. The clearest antidote to selfish ambition is to purify our intentions and to make sure that what we learn and accomplish is for the good of others. St. John Chrysostom said that to be rich is not to possess many things but to give many things away. Let us be rich according to the tradition of Chrysostom and the saints, living at the service of others.

Subscribe to the newsletter to never miss an article.