Classes begin on my campus in three weeks. That, in the middle of a pandemic, is enough in itself to cause everyone involved some sleepless nights. But even in “normal” times, the final weeks before the new academic year begins is stressful for professors, as we scramble to complete all of the various tasks and preparations that we have put off all summer.

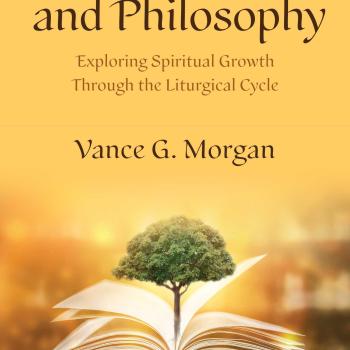

The first reading assignment in the interdisciplinary course that I will be team-teaching with two friends and colleagues from the history and English department is Pope Francis’ 2015 environmental encyclical Laudato Si’, subtitled “On Care for our Common Home.” It stirred up a good deal of controversy when it was published five years ago—as I have reread it over the past few days, I am reminded of why. I am also reminded of my own experiences as a non-Catholic in Catholic higher education for more than three decades.

It stirred up a good deal of controversy when it was published five years ago—as I have reread it over the past few days, I am reminded of why. I am also reminded of my own experiences as a non-Catholic in Catholic higher education for more than three decades.

Remember back in the old days when a spokesperson for some medical product on television would say “I’m not a doctor, but I play one on TV”? I have a similar sort of authority when it comes to things Catholic. I am not Catholic (I don’t think I even met a Catholic until my late teens), but my more than thirty years of, first, being educated by Jesuits in my PhD program, then teaching in Catholic institutions of higher education, qualify me to chime in on things Catholic on occasion. And with increasing frequency over the past several years I am saying five words that I never thought I would hear myself say: I really like this Pope.

I was raised in a conservative, evangelical Protestant religious tradition. The first time I ever heard about something called a Pope was in 1965 when Pope Paul VI visited the U.S. I was nine years old and recall seeing highlights on our little black-and-white television from the nightly news. My parents sufficiently filled me in on what a Pope was for me to realize that this was important to some people (although not to us). For my family, the most memorable portion of the visit was when the pontiff stepped off the plane at LaGuardia airport and the wind blew his cape over his head. The draped Pope looked like my dachshund peeking out from under a blanket, a source of great laughter and irreverence in my household.

As I moved into adulthood and learned a bit more about these people called Catholics (and actually met a few), other Popes crossed my radar screen (please understand that the following observations are the product of viewing things through barbarian Protestant lenses). The Pope prior to Paul VI, John XXIII, was an interesting guy, a supposed placeholder choice who threw everything into disarray and set the stage for change by convening Vatican II.

John Paul I, who followed Paul VI, poped just long enough to meet and hear the confession of the aging Michael Corleone before dying under suspicious circumstances in Godfather III (loosely interpreted). His successor John Paul II, who contributed greatly to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of Communism, also managed to set the clock back decades in his church on many social issues and helped produce a generation of priests who proceed as if Vatican II never happened. Then came Benedict XVI, whose best decision as pontiff was to step down from his position before he messed things up any further.

Now there’s Pope Francis. Everyone knew that things might be different when the first Jesuit and the first non-old-white-guy-from-Europe since the Syrian Gregory III in 741 was elected. He’s Argentinian, from a part of the globe where liberation theology caught fire and where Catholic social thought with its preferential option for the poor has not been bumped aside in importance by issues like abortion and same-sex relationships as it has been all too often in the Northern hemisphere of Catholicism.

Rejecting many of the accoutrements that traditionally accompany being God’s go-to person, Pope Francis lives humbly (comparatively speaking) and has a refreshing (or worrisome, depending on who you are) tendency to say what he is thinking and feeling without checking with his multitude of handlers ahead of time. This, of course, sends the holy spin-doctors into hyper drive trying to explain what Francis really meant, when it is usually pretty clear that he meant what he said.

I have a number of Catholic friends and colleagues who have struggled mightily since Francis became Pope to convince me that everything he is saying is consistent with a seamless, conservative Catholic position that encompasses every issue imaginable. I’m not buying it. Not for their lack of trying, but because in the real world a seamless, all-encompassing perspective that is consistent from stem to stern across all possible issues is a pipe dream, particularly when insisting that such a framework be stuffed into the rigid “conservative” or “liberal” straitjackets that we insist everything fit into.

What is one to do when a Pope who advocates all of the familiar conservative positions on abortion and the ordination of women produces an encyclical like Laudato Si’, which contains statements and positions on environmental issues so liberal as to cause Fox News pundit Greg Gutfield, shortly after Laudato Si’ was published, to label Francis as a “Marxist” and “the most dangerous man on the planet”?

Is Pope Francis the Most Dangerous Person Alive?

According to Gutfield, “[Francis] wants to be a modern pope. All he needs is dreadlocks and a dog with a bandana and he could be on Occupy Wall Street.” Gutfield’s problem has nothing to do with Catholic doctrine or orthodoxy; rather, Gutfield is outraged because many of Francis’s explicit claims and prescriptions in Laudato Si’ are rooted in a deep suspicion of unfettered capitalism and its accompanying worship of private property.

Someone once said that the mark of a good Supreme Court decision is one that makes neither side happy. If that is also the mark of an effective papacy, Pope Francis is doing a good job. Liberals applaud his emphasis on the poor, environmental issues, and his lack of interest in the over-the-top and gaudy trappings of being the pontiff but are quick to point out that nothing has really changed yet—doctrine remains the same. There is enough in what Francis says and does to somewhat mollify conservative Catholics worried that he really does want to turn the Vatican into a home for liberation theology.

Conservatives, however, worry that Francis’s words actually mean something—that in his heart of hearts he is setting the stage for an overhaul of the institution he leads that will make Vatican II pale in comparison. As a very interested outside observer, it seems to me that this is a classic case of “nothing has changed, but everything is changing.”

One of my best friends is a Catholic theologian; we taught together on the faculty of the college I teach at for several years before he took a position at another university twenty years or so ago. He loves the Catholic church, but is a powerful critic of many of its doctrines and much of its structural and bureaucratic nonsense in a way that only a fully knowledgeable insider can be.

I recently read and commented on a draft of his next book, in which he calls, among other things, for the Catholic church to ordain women, embrace LGBTQ people with no qualifications or reservations, and to vastly expand the power of the laity in the administration of the church. These are all radical ideas, none of which is likely to happen fully during my lifetime. But as a long-standing interested outsider, I’m encouraged that such necessary and morally imperative changes are more likely to happen in due season because of Pope Francis.

The prophet Micah (I seem to be bumping into him a lot lately in this blog) succinctly summarizes the heart of faithfulness to the divine in the Jewish scriptures: “What does the Lord require of you but to do justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God?” In the spirit of his namesake from Assisi, Francis has the humility thing pretty much down. Although Micah’s directive is intended for individuals and not institutions, Francis’ papacy has been dedicated to tempering justice with mercy.

Justice, when understood as the application of relevant and appropriate rules and doctrinal pronouncements, has been the bread and butter of the Catholic Church since somebody thought up the idea. Francis has shown in many ways that a precise following and application of the rules actually can undermine the heart of justice, turning it cold and clinical. Without seeking to change church teaching on abortion and annulment, for instance, Francis reminds the faithful that in such issues and innumerable others the actual human beings involved must not be ignored.

When just a few months into his papacy Francis said “If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?” I knew that there was a new pontifical sheriff is in town. Not that my non-Catholic opinion matters that much, but I’ll say it again: I really like this Pope.