Two weeks ago, I gave the First Sunday of Advent sermon at Trinity Episcopal Church in Pawtuxet, RI. The church’s priest-in-charge, my good friend Mitch, introduced me by saying “We are pleased to welcome to the Trinity pulpit this morning our own Advent prophet, Dr. Vance Morgan.” This was, without a doubt, the first time I have ever been introduced as a prophet, and it knocked me off my game for a few seconds. Because I know something about prophets. I grew up with one.

The Third Sunday of Advent is always John the Baptist Sunday; today’s reading from the Gospel of John places us in John’s world as he “prepares the way” for the one who we await. It also reminds me of a man with whom I had a tenuous relationship, but whom I miss a great deal.

On a beautiful, crystal clear June afternoon in 2002 I sat in an alpine meadow at the foot of the spectacularly majestic Grand Tetons in northwestern Wyoming. A handful of family was gathered to pay final respects to and spread the ashes of my father, who had died a few months earlier.

On the porch of my brother’s house that morning, I had considered what scripture text might be appropriate to read as we honored a man who had memorized massive amounts of scripture in his lifetime, a man whom many considered to be a prophet (as he considered himself to be), a man whose life and teaching had been a catalyst of liberation in the lives of many for whom the traditional church no longer gave life, and with whom I had maintained a tenuously “okay” relationship for most of my life.

My brother was always closest to my Dad, but it fell to me, the academic one, to find the suitable text. Sitting on a rock in that meadow next to my son Justin, who could barely keep his emotions in check, I read the following verses from Isaiah that are today’s reading from the Jewish scriptures, verses that had jumped off the page through my tears that morning:

The Spirit of the Lord God is upon Me,

Because the Lord has anointed Me

To preach good tidings to the poor;

He has sent Me to heal the brokenhearted,

To proclaim liberty to the captives,

And the opening of the prison to those who are bound . . .

To comfort all who mourn, To console those who mourn in Zion,

To give them beauty for ashes,

The oil of joy for mourning,

The garment of praise for the spirit of heaviness;

That they may be called trees of righteousness,

The planting of the Lord, that He may be glorified.

Scholars tell us that these verses are prophetic of the Messiah to come, but my father would have embraced this text as descriptive of his own calling, particularly to “proclaim liberty to the captives” whose lives had been stagnated or ruined by organized religion. As I choked my way through the reading on that summer afternoon—tears filled my eyes today, almost twenty years later, as I typed the words into my computer–I knew that “Mad Eagle,” as we sometimes called him when he wasn’t around, would have approved.

One of my favorite Biblical texts is from the Gospel of Luke and involves the passage from Isaiah that I read at my father’s memorial service. Jesus is fresh off his forty days and nights of temptation in the desert and returns to Nazareth, his home town. What better place to kick off his ministry?

The scene is powerfully portrayed in the 1977 Franco Zeffirelli television mini-series “Jesus of Nazareth.” It is the Sabbath, and Jesus is in the synagogue with wall-to-wall men and boys, while the women of the town observe from behind a screen. Although it is apparently not his turn to read, Jesus steps to the front and takes the scroll. After a pregnant pause, he begins to read. “The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me, Because the Lord has anointed me to preach good tidings to the poor . . .” Exactly the same verses from Isaiah that I read in that alpine meadow over a decade ago. When he is finished, Jesus rolls up the scroll, makes eye contact with the congregation, and says “Today, in your hearing, this Scripture is fulfilled.”

As the camera slowly pans the faces of those at the synagogue, their expressions pass from piety, to confusion, to outrage and anger. For every man and woman present knows that this scripture can only be fulfilled by the Messiah. And they know who this man is. He is Mary and Joseph’s son. He is a carpenter—a bit odd at times, but just like they are. Nazareth is an insignificant town in an insignificant backwater of the eastern Roman Empire. “I remember when I chased you out of my bakery for stealing a fig,” one thinks. “I remember when I had to break up a squabble between you and my son when you were teenagers,” thinks another. And he has just declared himself to be the son of God. No wonder they tried to kill him.

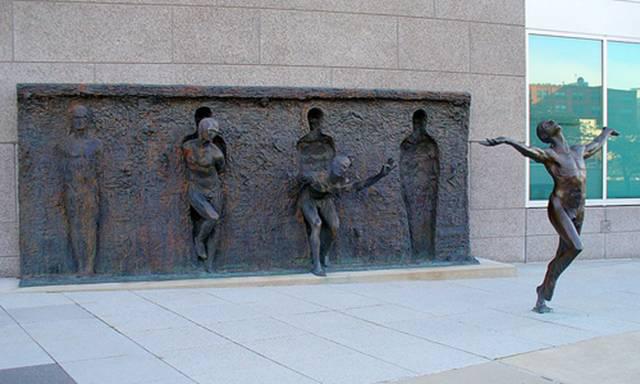

Christians believe that, despite the appropriate incredulity of his fellow worshippers on that Sabbath, Jesus was indeed the Messiah, God in flesh. Remarkable and astounding. But even more remarkable is that these twenty-five hundred year old words from Isaiah were not only fulfilled by Jesus–they continue to be fulfilled by God in human form. Isaiah’s prophecy foretells a time when healing, justice and liberation will be brought to the sick, oppressed and prisoners.

That time is now, and we are the vehicles of that healing, justice and liberation. Our world is full of the poor, the bound, those who mourn, those who are in captivity both physically and mentally. We live in a world crying out for liberation, peace, and consolation at every level. So often we wonder where God is, where the divine solution to the never-ending problems and tragedies of our world is to be found.

But we miss the clear answer to our questions. Joan Chittister writes that

[H]aving made the world, having given it everything it needs to continue, having brought it to the point of abundance and possibility and dynamism, God left it for us to finish. God left it to us to be the mercy and the justice, the charity and the care, the righteousness and the commitment, all that it will take for people to bring the goodness of God to outweigh the rest.

We are to be the oil of joy for those who mourn, to be the beauty in the midst of ashes, and to wrap the heavy of heart in the garment of praise. As the closing prayer in each Eucharistic celebration in the Episcopal liturgy asks, “send us now into the world in peace, and grant us strength and courage to love and serve you with gladness and singleness of heart.”