Is it ever right to hold a grudge? Is resentment or unforgiveness ever justified? These questions were front and center in a seminar with a bunch of freshmen not long ago; their answers revealed one of the most important and ubiquitous moral divides of all—the divide between what we think we should believe and what we actually believe. And behind the discussion loomed an even larger moral issue:  Where does a person’s moral compass come from, and is there any way of determining whether that moral compass is accurate?

Where does a person’s moral compass come from, and is there any way of determining whether that moral compass is accurate?

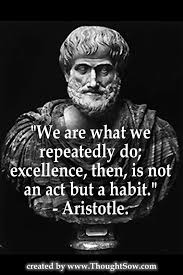

I’ve been teaching philosophy for more than thirty years and there are few areas of philosophy or philosophers that have not shown up somewhere in my classroom over those years. Ethics is my favorite systematic area of philosophy to teach on an introductory level, because ethics is where the often esoteric and abstract discipline of philosophy intersects immediately and directly with real life. And in the world of ethics, no philosopher ever got it better than Aristotle.

Aristotle’s framework for thinking about and trying to live the moral life is flexible, dynamic, creative, and practical, providing broad but identifiable boundaries for the life of human excellence within which each individual human being has the opportunity to make many important choices about what sort of person she or he will be. Aristotle’s ethic avoids both the Scylla of absolute and rigid moral rules and the Charybdis of “anything goes” relativism by continually reminding us that there is a point to a human life, that some lives are clearly not worth living, and it is up to each of us to identify the purpose of our lives as we live out the process of shaping and defining that purpose.

The most important feature of Aristotle’s ethical vision is the virtues, which he identifies as “good habits,” habits that will more often than not facilitate the living of a flourishing human life. These he contrasts with vices, bad habits that tend to hinder the living of such a life.  The notion of the key to the moral life being habits rather than obedience to rules is often both intriguing and confusing to eighteen-year-old freshmen; in seminar I focused my students’ attention on the “virtues as habits” idea by first brainstorming with them to produce a list of a dozen virtues, then providing them with a list of Aristotle’s examples of such habits scattered through the portions of his primary text on ethics that we had read for the day.

The notion of the key to the moral life being habits rather than obedience to rules is often both intriguing and confusing to eighteen-year-old freshmen; in seminar I focused my students’ attention on the “virtues as habits” idea by first brainstorming with them to produce a list of a dozen virtues, then providing them with a list of Aristotle’s examples of such habits scattered through the portions of his primary text on ethics that we had read for the day.

There were many virtues on our list that are not on Aristotle’s list. Where, for instance, are humility, honesty, patience, love, faith and hope? Perhaps even more confusing are some of the items that Aristotle does include on his list that were not on ours. There were several such items—wittiness, high-mindedness and right ambition, for instance—which raised eyebrows and provided an opportunity to consider just how different Aristotle’s definition of virtue is from our own. But the item on Aristotle’s list that bothered my students the most was “just resentment,” the idea that one of the good habits that will facilitate the life of human excellence is being able to tell when forgiveness is appropriate and when is it better to hold on to one’s resentment. Aristotle did not list forgiveness as a foundational virtue but, as many of my students pointed out, we know better. Or do we?

“How many of you think that forgiveness is a virtue?” I asked my students—every hand went up. “How many of you can think of a situation in which it would be natural not to forgive?” Most hands, but not all, went up. I gave my own example of the latter. In the earlier years of my teaching career I often taught applied ethics courses, which usually turned out to be a crash course in various moral theories for a few weeks, which we then applied to four or five tough moral problems for the rest of the semester.

The issue of capital punishment, which I consider to be one of the toughest moral nuts to crack without making a mess, was often on the syllabus. I told my students that in the abstract I believe the best moral arguments are against capital punishment, starting with the simple point that to respond to harm with more harm reduces a society to the level of the person being punished. “But,” I quickly added, “I know that if someone killed my wife or my sons and was found guilty, if I lived in a state where the death penalty was on the books I would want to be the one to administer the lethal injection or pull the switch.” There’s a place where even if I have developed the habit of forgiveness, the habit of just resentment seems more appropriate.

Several students vigorously nodded their heads in agreement, but others pressed back. One student had learned an important lesson well from Socrates two weeks earlier when he told a friend why, even though he has an opportunity to escape his prison cell and execution, he will not do so. “Who are you damaging if you don’t forgive?” my student asked. “Not the guy who’s being executed. He’s dead. But you will never move on and will never get past what has happened if you carry resentment around for the rest of your life.” “What if I don’t want to move on?” I asked. “Then you’ll never be able to live Aristotle’s life of human flourishing,” she replied. Touché.

But most of my students agreed that to forgive indiscriminately is not natural to human beings, despite the psychological damage that accompanies lack of forgiveness. “So where did we get the idea that we must forgive regardless of the situation?” I wondered. “We certainly learned that long before we considered that not forgiving might hurtful to ourselves.” “I learned it in church,” one said, while another said that she had learned it in school (which, since it was a parochial school, is pretty much the same as learning it in church).

That strikes me as the real truth. I learned that universal forgiveness is a virtue because I was taught at an early age that a first century Jewish carpenter said that we must love our enemies and told one of his followers that he should forgive his neighbor not the very challenging seven times but the impossible seventy times seven.  Aristotle perhaps doesn’t put such a habit on his virtue list because he lived more than three centuries before the Jewish carpenter and was not inclined to include on his list habits that are humanly impossible.

Aristotle perhaps doesn’t put such a habit on his virtue list because he lived more than three centuries before the Jewish carpenter and was not inclined to include on his list habits that are humanly impossible.

Truth be told, we all have the foundational pieces of our moral lives given to us long before we develop the capacity to challenge them—and often we never get to the challenge part. I usually urge my students to question and challenge what they have never questioned and challenged. But on this given day it struck me that in addition to questioning, it is equally important to first identify what we have been given. The fact that my students thought Aristotle was wrong about just resentment because they had been carrying around the directive to forgive their whole life was not mistaken—it is just a fact. The Jewish carpenter was on display a few weeks later in seminar, and we remembered Aristotle.

I n The Leopard, a crime drama by Jo Nesbo, the main character, an extraordinarily complex person in every way imaginable, is berating himself because he can’t seem to move past some inhibitions he has carried his whole life. A colleague suggests that he should relax.

n The Leopard, a crime drama by Jo Nesbo, the main character, an extraordinarily complex person in every way imaginable, is berating himself because he can’t seem to move past some inhibitions he has carried his whole life. A colleague suggests that he should relax.

You can’t just disregard your own feelings like that, Harry. You, like everyone else, are trying to leapfrog the fact that we are governed by notions of what’s right and wrong. Your intellect may not have all the arguments for these notions, but nonetheless they are rooted deep, deep inside you. Right and wrong. Perhaps its things you were told by your parents when you were a child, a fairy tale with a moral your grandmother read, or something unfair you experienced at school and you spent time thinking through. The sum of all these half-forgotten things. “Anchored deep within” is in fact an appropriate expression. Because it tells you that you may not be able to see the anchor in the depths, but you damn well can’t move from the spot—that’s what you float around and that’s where your home is. Accept the anchor.