There is a mystery in reading, a mystery which, if we contemplate it, may well help us, not to explain, but to grab hold of other mysteries in human life. Simone Weil

My early years were full of apocryphal stories of how I learned to read. According to my mother, I was reading by age three without anyone having taught me how to do it. I was never without a book, and lined up my menagerie of stuffed animals on the couch to read to them. Knowing how stories tend to take on a life of their own, I cannot attest to the accuracy of these reports (although it was my father rather than my mother who was prone to telling tall tales). I do know that my love of books extends as far back as I can remember, and that I know how to read before I could tell time or tie my shoes—perhaps my parents should have provided me with instruction manuals to read. Because I could read on a fifth grade level before starting first grade, according to the school board member who tested me at home, I went through first and second grade in one year. moving from one side of the room to the other in our little school after Christmas break.

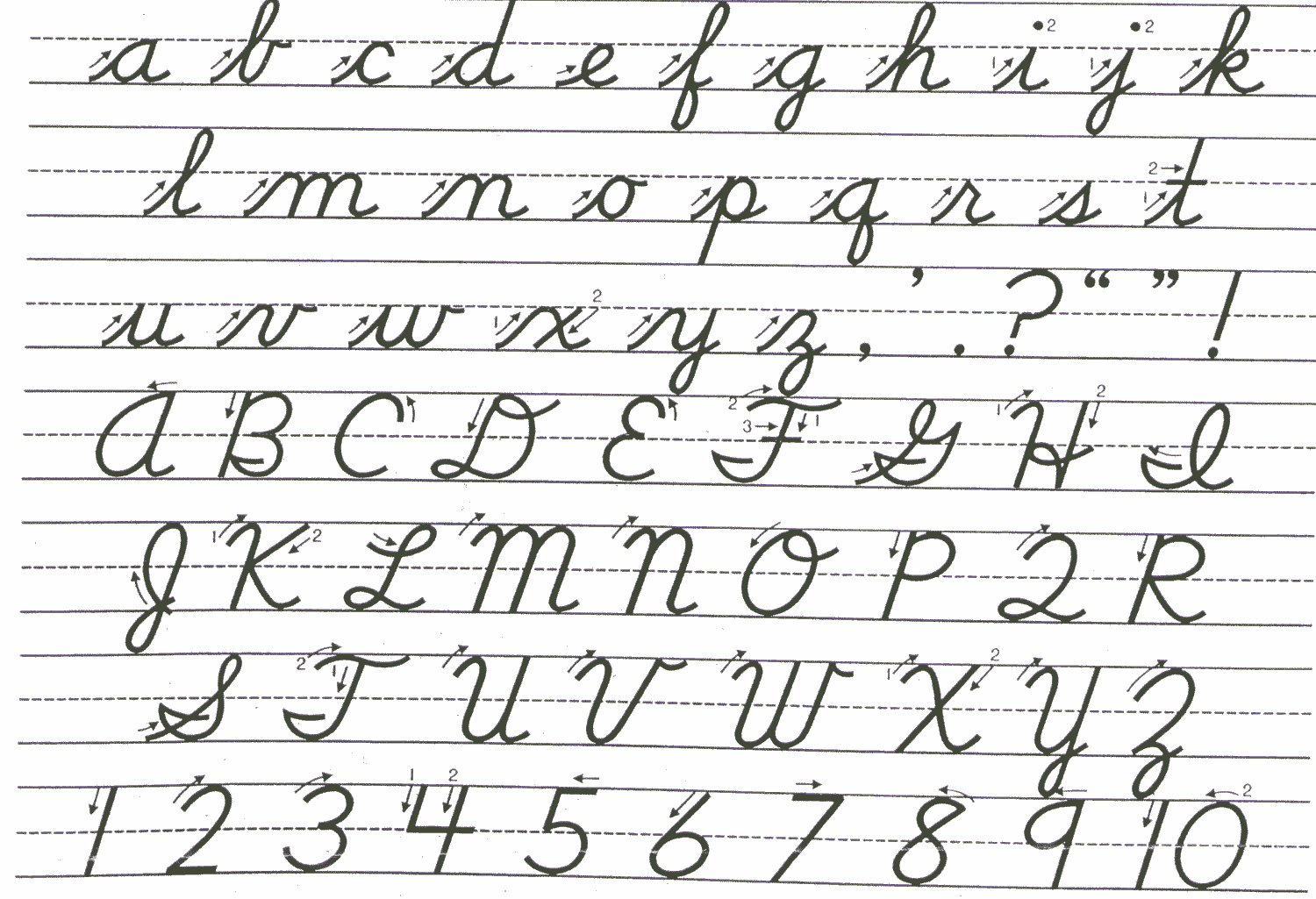

My early years were full of apocryphal stories of how I learned to read. According to my mother, I was reading by age three without anyone having taught me how to do it. I was never without a book, and lined up my menagerie of stuffed animals on the couch to read to them. Knowing how stories tend to take on a life of their own, I cannot attest to the accuracy of these reports (although it was my father rather than my mother who was prone to telling tall tales). I do know that my love of books extends as far back as I can remember, and that I know how to read before I could tell time or tie my shoes—perhaps my parents should have provided me with instruction manuals to read. Because I could read on a fifth grade level before starting first grade, according to the school board member who tested me at home, I went through first and second grade in one year. moving from one side of the room to the other in our little school after Christmas break.  I’ve paid a lifelong price for that honor—I joined second grade when they were all the way to the letter “W” in their cursive writing studies. My “w’s.” “x’s,” “y’s” and “z’s” are fabulous, but other than that my cursive has been illegible, even to me, ever since.

I’ve paid a lifelong price for that honor—I joined second grade when they were all the way to the letter “W” in their cursive writing studies. My “w’s.” “x’s,” “y’s” and “z’s” are fabulous, but other than that my cursive has been illegible, even to me, ever since.

Several years ago during an eye exam, my new ophthalmologist asked “do you read very much?” I laughed as I said “I read for a living!” The written word is not only the foundation of my professional life, but has also been my spiritual lifeline for most of my life. For many years all that remained of my religious upbringing was the Bible.  Even though I no longer believed it to be the literally inerrant word of God as I was taught, large portions of it resided in my memory, ready to be accessed in class and conversation as well as popping up even when uninvited. I memorized large portions of the Bible growing up, as all good Baptist kids should, continually reminded that “Thy Word have I hid in my heart, that I might not sin against Thee.” We were taught that since the canon of Scripture was completed, we should not expect further communication from the divine in the form of miracles, signs and wonders, or direct communication. We already had God’s final word to us in completed form; now we just needed to obey it and hang on until the Second Coming.

Even though I no longer believed it to be the literally inerrant word of God as I was taught, large portions of it resided in my memory, ready to be accessed in class and conversation as well as popping up even when uninvited. I memorized large portions of the Bible growing up, as all good Baptist kids should, continually reminded that “Thy Word have I hid in my heart, that I might not sin against Thee.” We were taught that since the canon of Scripture was completed, we should not expect further communication from the divine in the form of miracles, signs and wonders, or direct communication. We already had God’s final word to us in completed form; now we just needed to obey it and hang on until the Second Coming.

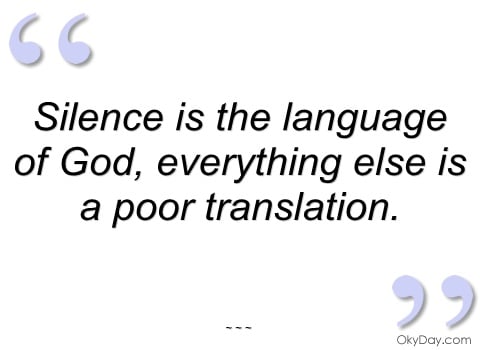

I was accordingly jerked up short a few years ago when I read in a book by theologian Patrick Henry that “God died because people forgot how to read.” I don’t entirely remember the context of the claim nor Henry’s explication, but I was reminded of the phrase this past week as I read a manuscript on  Simone Weil’s philosophy as an outside reader for a prestigious academic press. In her “Essay on the Concept of Reading,” she argues that we “read” everything in our environment. “The sky, the sea, the sun, the stars, human beings, everything that surrounds us is something that we read.” This is much broader understanding of “reading” than our traditional Western conception, which considers reading to be an exclusively cognitive, intellectual, and mental activity—precisely the sort of activity I’ve spent the majority of my waking hours on this planet doing. So how is it that such a crucial, human defining activity as reading could be forgotten, even to the point of emptying the divine of content? The problem is not with reading per se—it’s that we’ve forgotten that reading is not just an intellectual activity.

Simone Weil’s philosophy as an outside reader for a prestigious academic press. In her “Essay on the Concept of Reading,” she argues that we “read” everything in our environment. “The sky, the sea, the sun, the stars, human beings, everything that surrounds us is something that we read.” This is much broader understanding of “reading” than our traditional Western conception, which considers reading to be an exclusively cognitive, intellectual, and mental activity—precisely the sort of activity I’ve spent the majority of my waking hours on this planet doing. So how is it that such a crucial, human defining activity as reading could be forgotten, even to the point of emptying the divine of content? The problem is not with reading per se—it’s that we’ve forgotten that reading is not just an intellectual activity.  God’s death is not due to a misuse of or over-reliance on the activity of reading. It’s due to forgetting what true reading even is.

God’s death is not due to a misuse of or over-reliance on the activity of reading. It’s due to forgetting what true reading even is.

I had heard and read about “lectio divina,” sacred reading before I went on sabbatical to a  Benedictine college campus with a large abbey on site, but it had not struck me as a particularly interesting concept. Just another skill to learn, technique to master, perhaps—but really, if there’s one thing I know how to do pretty well, its reading. But after several weeks of daily prayer with the abbey monks, it dawned on me that lectio divina isn’t about words and meaning and retention at all. I often found that I did not remember, even for the amount of time it took to walk from the choir stalls to the front of the abbey and exit, which Psalms we had read nor any of the content. Yet I had a sense that what we were doing was far more important than reading a book, marking it with highlighter and pen in my usual method, and perhaps memorizing a phrase or two for future reference in class or conversation.

Benedictine college campus with a large abbey on site, but it had not struck me as a particularly interesting concept. Just another skill to learn, technique to master, perhaps—but really, if there’s one thing I know how to do pretty well, its reading. But after several weeks of daily prayer with the abbey monks, it dawned on me that lectio divina isn’t about words and meaning and retention at all. I often found that I did not remember, even for the amount of time it took to walk from the choir stalls to the front of the abbey and exit, which Psalms we had read nor any of the content. Yet I had a sense that what we were doing was far more important than reading a book, marking it with highlighter and pen in my usual method, and perhaps memorizing a phrase or two for future reference in class or conversation.

What was happening in the choir stalls was not a mind event, but a full body experience bypassing my overdeveloped mind and seeping into all the other parts of me that had been starved for years. My bodily rhythms, my intuitions, my emotions, my spirit. The Psalms speak of God’s word all the time, but almost never of thinking about God’s word.  It’s more like what Jeremiah reports: “The words were found and I did eat them, and thy word was unto me the joy and rejoicing of my heart.” Simone Weil was channeling her internal Jeremiah when she wrote that “I only read what I am hungry for at the moment when I have an appetite for it, and then I do not read, I eat.” And like a mother bird regurgitating food for the babies, an important word or phrase would come into my consciousness later in the day, one that I didn’t remember reading but which had dripped into my soul.

It’s more like what Jeremiah reports: “The words were found and I did eat them, and thy word was unto me the joy and rejoicing of my heart.” Simone Weil was channeling her internal Jeremiah when she wrote that “I only read what I am hungry for at the moment when I have an appetite for it, and then I do not read, I eat.” And like a mother bird regurgitating food for the babies, an important word or phrase would come into my consciousness later in the day, one that I didn’t remember reading but which had dripped into my soul.

In our “real world” of immediacy, getting it done, making money and a living, is there a place for what I began to absorb in a monastery abbey in the middle-of-nowhere Minnesota? Over the subsequent years I’ve seen small but important evidence of change in how I converse with people, how I approach the day, and a heightened and more immediate sense of when a layer is threatening to grow back over my divine reading space.  Learning how to read differently is not just another technique; because it is a new way of being, it is transferable to everything. I went on sabbatical expecting to write about trying to sustain a life of faith when God at best is a silent partner who never writes, calls, emails, texts or tweets. Now the divine is everywhere and seems to have a lot to say. Reading the divine begins with believing that everything is sacramental, infused with the breath of God, with taking “the Word became flesh” very seriously. All of creation is a sacred text. I didn’t know it, because I didn’t know how to read.

Learning how to read differently is not just another technique; because it is a new way of being, it is transferable to everything. I went on sabbatical expecting to write about trying to sustain a life of faith when God at best is a silent partner who never writes, calls, emails, texts or tweets. Now the divine is everywhere and seems to have a lot to say. Reading the divine begins with believing that everything is sacramental, infused with the breath of God, with taking “the Word became flesh” very seriously. All of creation is a sacred text. I didn’t know it, because I didn’t know how to read.