Although I read incessantly, I don’t read a lot of magazines. The only magazine I currently subscribe to is The Atlantic—I appreciate the excellent writing and quirky features, but don’t exactly wait by the mailbox for each monthly edition to show up. Instead, they tend to pile up on the little table next to my side of the bed, waiting to be perused when I am between authors in my novel reading. I’m currently in one of those spaces, having just finished my fourth consecutive Arturo Pérez-Reverte mystery a few days ago and not ready to start a new, large reading project just a week before the semester starts.  Accordingly, I started plowing through the three summer editions of The Atlantic that have accumulated on my nightstand since June. Inside the June edition, whose cover includes two-thirds of Donald Trump’s head peeking in from the right side announcing a lead article entitled “The Mind of Donald Trump” (an oxymoron if I ever saw one), I found this: “There’s No Such Thing as Free Will—Here’s why we all may be better off believing in it anyway.”

Accordingly, I started plowing through the three summer editions of The Atlantic that have accumulated on my nightstand since June. Inside the June edition, whose cover includes two-thirds of Donald Trump’s head peeking in from the right side announcing a lead article entitled “The Mind of Donald Trump” (an oxymoron if I ever saw one), I found this: “There’s No Such Thing as Free Will—Here’s why we all may be better off believing in it anyway.”

Stephen Cave: There’s No Such Thing As Free Will

The article is by Stephen Cave, a philosopher who runs a “Center for the Future of Intelligence” at the University of Cambridge. His article is well-written and engaging—so much so that I suspect he may have had help with it. Trust me, I know whereof I speak. I have spent over twenty-five years learning to write in ways that make core philosophical issues accessible and interesting to non-philosophers—it ain’t easy. First, it’s important to clarify what philosophers usually are referring to when they use terms like “free will” or “freedom.” Just before the final battle in his 1995 epic “Braveheart,” Mel Gibson’s William Wallace screams to the Scottish army that They may take our lives, but they’ll never take our freedom!!

The article is by Stephen Cave, a philosopher who runs a “Center for the Future of Intelligence” at the University of Cambridge. His article is well-written and engaging—so much so that I suspect he may have had help with it. Trust me, I know whereof I speak. I have spent over twenty-five years learning to write in ways that make core philosophical issues accessible and interesting to non-philosophers—it ain’t easy. First, it’s important to clarify what philosophers usually are referring to when they use terms like “free will” or “freedom.” Just before the final battle in his 1995 epic “Braveheart,” Mel Gibson’s William Wallace screams to the Scottish army that They may take our lives, but they’ll never take our freedom!!

That sort of freedom, the kind enshrined in this country’s founding documents as “rights” that each citizen possesses and that must not be violated or taken away, is not what philosophers mean by freedom.

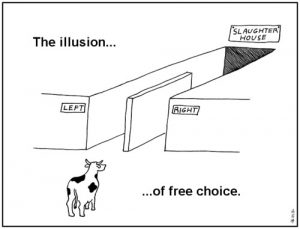

Instead, “free will” refers to the human ability to choose, for a person to deliberate between options and eventually choose, then act on one of the options, all the time knowing that she or he did not have to choose that option— in other words, she or he could have chosen otherwise. This vaunted human ability to freely choose is, for many (including me), the fundamental and defining feature of what it means to be human. Stephen Cave points out that our legal systems, as well as our general beliefs concerning praise, blame, reward, punishment, and all things moral depend on our basic belief in human free will. And it is under attack—scientists, psychologists, philosophers, and just about everyone “in the know” have been trying to take it away for decades.

in other words, she or he could have chosen otherwise. This vaunted human ability to freely choose is, for many (including me), the fundamental and defining feature of what it means to be human. Stephen Cave points out that our legal systems, as well as our general beliefs concerning praise, blame, reward, punishment, and all things moral depend on our basic belief in human free will. And it is under attack—scientists, psychologists, philosophers, and just about everyone “in the know” have been trying to take it away for decades.

The “free will issue” is a go-to problem in all philosophy courses, the philosophical version of the divine foreknowledge/free will problem in theology. Just it is impossible to make room for free choice in a world governed by an omniscient deity, so in a world where everything that occurs is governed in a cause-and-effect manner by the physical laws of matter, there is no room for true human free will. Cave points out that at least since Darwin argued in The of Species that everything about human beings—including our vaunted reasoning abilities where the ability to choose is located—is a result of natural evolutionary processes rather than a mystical, magical, or divine “spark” that lies outside the physical laws of matter,  science has reinforced the conclusion that whatever human consciousness and deliberate choice are, they are to be placed squarely in the material world. Making it impossible, of course, to squeeze out the special place we desire for choice. Our choices may “feel” free, “as if” they are up to us, but Cave pulls no punches in describing the truth about us:

science has reinforced the conclusion that whatever human consciousness and deliberate choice are, they are to be placed squarely in the material world. Making it impossible, of course, to squeeze out the special place we desire for choice. Our choices may “feel” free, “as if” they are up to us, but Cave pulls no punches in describing the truth about us:

The contemporary scientific image of human behavior is one of neurons firing, causing other neurons to fire, causing our thoughts and deeds, in an unbroken chain that stretches back to our birth and beyond. In principle, we are therefore completely predictable. If we could understand any individual’s brain architecture and chemistry well enough, we could, in theory, predict that individual’s response to any given stimulus with 100 percent accuracy.

Experiments by psychologists and neuroscientists have shown that the brain’s neurons fire in new patterns causing a specific action before a person consciously “chooses” to act—indicating that my conscious “choice” is an illusion that actually doesn’t cause anything.  Debates rage concerning how much a human’s actions are caused by “nature”—one’s hardwiring—and how much is caused by “nurture”—one’s environment—but there is general agreement that none of them are caused by conscious choice. We are determined through and through.

Debates rage concerning how much a human’s actions are caused by “nature”—one’s hardwiring—and how much is caused by “nurture”—one’s environment—but there is general agreement that none of them are caused by conscious choice. We are determined through and through.

The ensuing discussion is often amusingly similar to conversations that couples considering a divorce might have: Should we tell the children, and if so, when? In the service of all truth all the time, some argue that non-philosophers and non-scientists should be made aware that free choice is an illusion and they should stop believing in it. Others insist that such a revelation would be damaging to the basic human’s commitment to morality, law, reward, punishment, and all of the other cool things that rely on our apparently mistaken belief that our choices make a difference and that we are responsible for them. My own classroom experiences indicate that it doesn’t matter. I regularly use a very simple thought experiment with my students at the beginning of the “free will” unit on the syllabus:

Suppose that in the near future a super-duper computer can read your brain and physiology sufficiently to predict the rest of your life, from large events to the minutest second-to-second thoughts and feelings, from now until you die. For a nominal fee you can purchase a printout of every event, thought, and feeling that you will experience for the rest of your life. Some printouts will be yards in length, while others will be very short. Do you want to see yours?

In a typical class of twenty-five students, no more than one or two students will say that she or he wants to see it. Why? Because even with direct proof available that the rest of my history is determined down to the minutest level—including my “free” choices— I prefer to believe that my choices make a difference in my life and in the world around me. I prefer to embrace the illusion. It appears, in other words, that human beings are determined to believe that they are not fully determined.

I prefer to believe that my choices make a difference in my life and in the world around me. I prefer to embrace the illusion. It appears, in other words, that human beings are determined to believe that they are not fully determined.

On this particular issue I find myself swimming against the tide. I not only believe that human beings have the ability, at least on occasion, to make choices that are not entirely determined by their biology, history, and environment—I also believe that this ability is not an illusion. It’s real. The free will/determinism issue as contemporary philosophy defines it has its current shape because virtually everyone accepts a starting assumption—everything that exists is material stuff subject to inflexible physical laws. Given that assumption, the claim that human beings have the capacity to jump outside the limitations of matter and make choices that avoid the determinism of cause and effect makes no sense. But as I often tell my students, if the answers one is getting are unacceptable, change the question. If the ability to freely choose is fundamental to what a human being is, and if our current assumptions about how reality is constructed make no room for that ability, then perhaps instead of accepting that choice is an illusion we should challenge the assumptions that forced us to this acceptance. Be watching for “What Freedom Amounts To” next week, where I’ll describe a very different way to think about human choice!