We ought not to hide from ourselves that Nazi Germany is a mirror for all of us. What looks to us so hideous is our own features, but magnified. Simone Weil in 1937

One of my favorite weekly activities is to gather every Friday afternoon at MacPhail’s, our on-campus watering hole, with any number of faculty colleagues to down a beer or two (or three) as we mark the end of the week and the beginning of the weekend. Last Friday was no exception. It was inauguration day, which—as I described that day on this blog—I was not watching.

our on-campus watering hole, with any number of faculty colleagues to down a beer or two (or three) as we mark the end of the week and the beginning of the weekend. Last Friday was no exception. It was inauguration day, which—as I described that day on this blog—I was not watching.

As is often the case, I was the first person to arrive. I sat in our usual area with my back to the three television screens over the bar, on which the new President’s poorly attended inaugural events were being covered.  Having established the habit many years ago of never being without something to read if there was any chance I might have to wait for anything for more than thirty seconds, I reached into my book bag, pulled out the central text that I would be working with in one of my classes the following week, and settled in to knock off a few pages. When a colleague and friend from the chemistry department showed up a few minutes later, it occurred to me that there was a strange synchronicity between what was on the television screens behind me and what I was reading. “Look at what I’m reading, Seann!” I said, passing the book to him.

Having established the habit many years ago of never being without something to read if there was any chance I might have to wait for anything for more than thirty seconds, I reached into my book bag, pulled out the central text that I would be working with in one of my classes the following week, and settled in to knock off a few pages. When a colleague and friend from the chemistry department showed up a few minutes later, it occurred to me that there was a strange synchronicity between what was on the television screens behind me and what I was reading. “Look at what I’m reading, Seann!” I said, passing the book to him.  He broke into laughter as he saw Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. You can’t make this stuff up.

He broke into laughter as he saw Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. You can’t make this stuff up.

I am in the early stages of teaching an interdisciplinary colloquium with a colleague from the history department: “‘Love Never Fails’: Grace, Truth, and Freedom in the Nazi Era.” This is the third time in the past four years we have offered this colloquium; it is the most wildly popular course I have ever taught, filling up immediately on registration day with a list of dozens of students on a waiting list hoping to get in. I would love to think that the colloquium’s popularity is due to my colleague’s and my teaching excellence, but the real reason everyone wants to take this course is simple: Nazis sell. Put the adjective “Nazi” together with any course content—Nazi Accounting, Nazi Calculus, Nazi Basket Weaving—and the class will fill up immediately. Like the worst train wreck ever, people can’t look away from the Nazis. Just about everyone agrees that they represent the worst that human beings can be, but still—or perhaps because of this—no one can look away.

This is not just the case in the educational world. Mention the Nazis in any public conversation and people’s ears prick up. Describing someone’s activities or attitudes as Nazi-like is the third rail of public discourse, a bridge too far even in the most vigorous debate. And yet it happens on a remarkably regular basis. The Nazi card was played frequently during the just completed Presidential campaign season, most recently a bit over two weeks ago when the then President-elect criticized the intelligence community for not prohibiting an unsubstantiated document containing damaging allegations from being published. “Are we living in Nazi Germany?” the President-elect tweeted,  a question that immediately met with outrage from many quarters, while at the same time attracting prurient interest because the Nazis had been invoked. Playing the Nazi card has been a popular activity on all sides of political arguments for the past fifty years. I recently finished reading Stephen Prothero’s Why Liberals Win (Even When They Lose Elections); in his final chapter on culture wars in this country from the 1970s to the present, he mentions at least a half-dozen different times when one side of a given squabble has accused the other side of Nazi-like behavior or beliefs.

a question that immediately met with outrage from many quarters, while at the same time attracting prurient interest because the Nazis had been invoked. Playing the Nazi card has been a popular activity on all sides of political arguments for the past fifty years. I recently finished reading Stephen Prothero’s Why Liberals Win (Even When They Lose Elections); in his final chapter on culture wars in this country from the 1970s to the present, he mentions at least a half-dozen different times when one side of a given squabble has accused the other side of Nazi-like behavior or beliefs.

Why do we do this? I’m sure that many articles, books, and dissertations have been written on the psychology and politics of Nazi-shaming, but on one level the attraction is obvious. If X accuses Y of Nazi-like behavior, X is intending to either derail the conversation entirely or deflect it in an entirely new direction. Except for skinheads, no one takes Nazi attributions lying down. To accuse someone of being or acting like a Nazi is to accuse her or him of being on the very outer fringes of humanity, perhaps having even crossed the line into non-humanity. But my impression is that no one really means it when they play the Nazi card—it’s just the worst thing the person can think of to say in the moment. Accusing someone of Nazi-like behavior is like accusing them of being an evil alien—and that’s a problem. Because the Nazis were people, no different at their core than the rest of us. We forget this at our peril.

Except for skinheads, no one takes Nazi attributions lying down. To accuse someone of being or acting like a Nazi is to accuse her or him of being on the very outer fringes of humanity, perhaps having even crossed the line into non-humanity. But my impression is that no one really means it when they play the Nazi card—it’s just the worst thing the person can think of to say in the moment. Accusing someone of Nazi-like behavior is like accusing them of being an evil alien—and that’s a problem. Because the Nazis were people, no different at their core than the rest of us. We forget this at our peril.

One of the most important tasks my teaching colleague and I seek to accomplish early in the semester when we teach our Nazi era colloquium is to convince the students that the Nazis were not aliens, monsters, or mutants. To consider them as such is to remove the possibility, at least theoretically, that we share anything in common with them. My colleague and I assign significant portions of Mein Kampf,  study the NSDAP’s “Twenty-Five Point Program” (the Nazis’ socio-political “platform”), and consider the lengthy chapter on Hitler’s tortured childhood from Alice Miller’s For Your Own Good, all with a view to realizing that understanding the Nazis requires first understanding that they were human beings just as we are. Human beings with histories, experiences, commitments, worries, fears, desires, hopes and dreams. Human beings who hoped for a better world than the one they believed had been unjustly imposed on them by outside forces. The policies and actions of the Nazis flowed logically from clearly stated premises and assumptions; the fact that these premises and assumptions differ sharply from those that most of us profess to be committed to does not prove them to be wrong. We urge our students to realize that dismissing the Nazis simply because they believed so differently than we do spares us from doing the difficult and important work of identifying exactly why we are committed to our beliefs and assumptions. Only if we recognize that the Nazis were human beings with whom we share a vast amount of things in common can we truly begin to consider carefully what went so monstrously wrong.

study the NSDAP’s “Twenty-Five Point Program” (the Nazis’ socio-political “platform”), and consider the lengthy chapter on Hitler’s tortured childhood from Alice Miller’s For Your Own Good, all with a view to realizing that understanding the Nazis requires first understanding that they were human beings just as we are. Human beings with histories, experiences, commitments, worries, fears, desires, hopes and dreams. Human beings who hoped for a better world than the one they believed had been unjustly imposed on them by outside forces. The policies and actions of the Nazis flowed logically from clearly stated premises and assumptions; the fact that these premises and assumptions differ sharply from those that most of us profess to be committed to does not prove them to be wrong. We urge our students to realize that dismissing the Nazis simply because they believed so differently than we do spares us from doing the difficult and important work of identifying exactly why we are committed to our beliefs and assumptions. Only if we recognize that the Nazis were human beings with whom we share a vast amount of things in common can we truly begin to consider carefully what went so monstrously wrong.  As Alice Miller writes, “all that it took was a committed Fuhrer and several million well-raised Germans to extinguish the lives of countless innocent human beings in a few short years.”

As Alice Miller writes, “all that it took was a committed Fuhrer and several million well-raised Germans to extinguish the lives of countless innocent human beings in a few short years.”

For those who believe that their religious faith provides them with a firewall against the elements of human nature regularly on display during the Nazi era, the story of the Christian churches, both Protestant and Catholic, in Germany during the time of the Nazis is both sobering and disturbing. People like Lutheran minister Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Franciscan priest Maximillian Kolbe are examples in our colloquium of persons who exhibited grace and truth during the Nazi era, but they were voices and persons of resistance. Large numbers of Christian pastors and priests, ministers and bishops, as well as their German Christian congregations, not only supported the policies of Hitler and the Nazis but also truly believed that this support was sanctioned and supported by their commitment to their Christian faith.  It did not turn out to be that difficult for millions of good Germans to find a way to be both believers in Christianity and supporters of Nazism.

It did not turn out to be that difficult for millions of good Germans to find a way to be both believers in Christianity and supporters of Nazism.

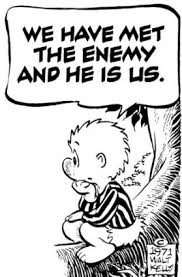

I spent a great deal of time on this blog over the past many months wondering how evangelical Christians, millions of Catholics, and many others with whom I share my Christian faith could square their faith with their political commitments and how they voted in the recent Presidential election. I’m still wondering, but returning to the Nazis has reminded me that human beings can convince themselves that absolutely anything is true, as well as believing that incompatible beliefs are actually compatible, if they are sufficiently motivated by their experiences, circumstances, fears, and anger to do so. That includes me. The next time the Nazi card get played publicly, we would do well to not treat it as twisted entertainment or the tweetings of uninformed people with too much time on their hands. As offensive as it may sound, each of us has a Nazi inside of us—only regular vigilance and a constant refusal to be duped or complacent can silence it. As Pogo told us many years ago, we have met the enemy—and he is us.