During the Providence Friars’ recent exciting basketball season, Jeanne and I frequently watched a replay of the team’s most recent win the next day online. Every game has its ebbs and flows, including moments when in real time it appears that we are headed for defeat. The virtues of watching a replay the next day when the positive outcome is already known include no stress and the opportunity to savor the best plays in a way that is impossible in real time. Mind you, we have never watched a replay of a Friars loss—why submit ourselves voluntarily to an experience that we know ends badly? Even the worst of times can be weathered and perhaps appreciated when one knows that things work out in the end. Jeanne’s and my habit is entirely harmless when confined to our love of college basketball,  but this is also how millions of Christians tend to treat Good Friday, the darkest day in the liturgical year.

but this is also how millions of Christians tend to treat Good Friday, the darkest day in the liturgical year.

In the religious tradition of my youth, Good Friday was a speed bump on the way to Easter. Our theology was what scholars call a “theology of glory,” one that emphasizes the power and glory of God as exemplified through Christ’s sacrifice for the sins of the world on Good Friday and his triumphant resurrection from the dead three days later. It is difficult to pay more than twenty-four hours of attention to the suffering and agony of the cross when you know that it all ends up in the right place. Although I left many features of my conservative Protestant upbringing in my rear view mirror decades ago, I did not start thinking differently about Good Friday and Easter until I encountered Simone Weil’s work for the first time twenty-five years ago.  Weil writes that “The death on the Cross is something more divine than the Resurrection,” and suggests that the heart of Christianity would be complete with the Crucifixion even without the Resurrection. What happens if the focus of one’s Christian faith is Good Friday rather than Easter?

Weil writes that “The death on the Cross is something more divine than the Resurrection,” and suggests that the heart of Christianity would be complete with the Crucifixion even without the Resurrection. What happens if the focus of one’s Christian faith is Good Friday rather than Easter?

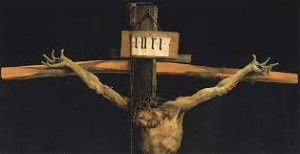

The Crucifixion without anticipating the Resurrection first moves our attention away from glory, power, and triumph, instead focusing us on suffering, pain, and weakness. This in itself brings home the fundamental fact of Christian belief—God became human, with an emphasis on the human part. This is something that a theology of glory tends to de-emphasize, at the risk of turning away from the most fundamental truths of the human experience. A couple of years ago I had a discussion with my after-church adult education group about the end of the  Book of Job in the Jewish Scriptures, an ending tacked on long after the main story had been written in which after forty some chapters of suffering Job gets back everything that he had lost. I asked the group why someone might have found it necessary to add this “happily ever after” ending to such a dark and human story. “Because the original ending is too tough,” someone suggested. “Because people want to believe that the suffering has a point, that it is all for something,” another contributed. “Which makes the better story?” I asked. The original or the one with the new ending? “The original is truer,” an eighty-something regular participant said. “People don’t come back. Things that you lose don’t return.” And she was right.

Book of Job in the Jewish Scriptures, an ending tacked on long after the main story had been written in which after forty some chapters of suffering Job gets back everything that he had lost. I asked the group why someone might have found it necessary to add this “happily ever after” ending to such a dark and human story. “Because the original ending is too tough,” someone suggested. “Because people want to believe that the suffering has a point, that it is all for something,” another contributed. “Which makes the better story?” I asked. The original or the one with the new ending? “The original is truer,” an eighty-something regular participant said. “People don’t come back. Things that you lose don’t return.” And she was right.  A theology that depends on a triumphant, happy ending is one that runs the risk of failing to address the human condition as we find it.

A theology that depends on a triumphant, happy ending is one that runs the risk of failing to address the human condition as we find it.

In contrast to a theology of glory, the God of a theology of the cross addresses the human condition, not by overcoming it, but by becoming part of it. The vast distance between the human and the divine is mediated by the divine becoming incarnated in flesh and thus becoming subject to everything that human beings are subject to—including suffering and death.

Incarnation and crucifixion are expressions of love; resurrection is an expression both of love and power. Simone Weil focuses on the Crucifixion rather than the Resurrection in order to counter our common tendency to rush ahead to the Resurrection, thus failing to recognize the depth of the agony and suffering required for Christ’s mediation. She does not deny the Resurrection; rather, she asks us not to let our joy at the risen Christ diminish our understanding of the price required for us to be made the friends of God.

After the Resurrection the infamous character of his ordeal was effaced by glory, and today, across twenty centuries of adoration, the degradation which is the very essence of the Passion is hardly felt by us . . . We no longer imagine the dying Christ as a common criminal.

The Incarnation and the Crucifixion focus our attention on unlimited love, something that we often are too quick to move past in our rush to a happy ending. But as Job tells us, “mortals die, and are laid low.” Good Friday reminds us that because of divine love the incarnated God did not seek to avoid this fundamental human experience.

St. Paul argued that the focal point of the Christian faith is the Resurrection: “If Christ be not raised, your faith is vain.” Simone Weil, however, asks us not to forget that more foundationally the Christian faith is vain if there is no Cross, no suffering and death of the divine mediator between God and humanity. Only when we see, as did the penitent thief, that the criminal hanging on a cross, rejected and despised by all, is the perfectly just God-man paying the ultimate sacrifice to achieve mediation between God and humanity will we begin to truly experience the mystery of the Christian faith. If the story ended with Jesus executed as a criminal and dead in a tomb, we still would have reason to believe in a God of love. Our very existence, as well as the existence of the reality we inhabit, is evidence of God’s choice to create in order to love. The story of a God who becomes fully human, who lives a life in time subject to all things each human being is subject to, including suffering, pain, loss, tragedy, injustice, and death serves to drive the point deeper. Good Friday reveals just how far the divine chooses to go with us—into the depths of despair and death.

Good Friday reveals just how far the divine chooses to go with us—into the depths of despair and death.

The other day Jeanne and I were talking about what the indispensable heart of Christianity might be. My contribution was that “God is love, and God is with us.” Stripped of millennia of doctrinal and dogmatic accretions, that’s what the Christian faith amounts to. And it is on full display on Good Friday with Jesus dying on the cross. Even if there was no Resurrection, the Crucifixion and Incarnation provide everything one needs to know about the human relationship with the divine. God is love. God is with us.