Have you never felt like one of those pawns forgotten in a corner of the board, with the sounds of battle fading behind them? They try to stand straight but wonder if they still have a king to serve. Arturo Pérez-Reverte

I am a great lover of mysteries. Arturo Pérez-Reverte, an internationally acclaimed Spanish author of mysteries and thrillers notable for their intricate and labyrinthine plots, is a current favorite. He’s good—not at the top of my list of mystery authors with Elizabeth George, Louise Penny, or P. D. James, but no more than one rung lower on the ladder of excellence. I just finished The Flanders Panel, a complicated and multi-layered story with a sixteenth-century painting by a Flemish master at the center. The painting depicts two men playing a game of chess, with an aristocratic woman reading a book by the window in the background—a game within a game within a game, as it turns out. I’m glad I know a little bit about chess, because its intricacies and strategies take center stage as various characters seek to decipher hidden clues in the painting that promise to reveal the story of a murder that inspired the work of art, as well as to shed light on more recent suspicious deaths.

Let me be clear—I am a horrible chess player. I learned the rules of the game and the movements of each piece from my Dad (also a horrible player), but I know nothing about strategy. The chess matches I have participated in over the years have been bloodbaths, similar to the Battle of the Bastards toward the end of the most recent season of “Game of Thrones.” I recall many games where the losing side had only a naked and solitary king left when things finally ended. You don’t need to know anything about chess to realize that when one piece is being chased around sixty-four squares by several hostile enemy pieces, checkmate will soon occur.

I taught my youngest son Justin the basics of chess as my father had taught me—my older son Caleb lacked the patience. Justin took the game far more seriously than I ever have, joining the chess club in high school and practicing at home when he could get me to play. “I’ll play you until you beat me,” I said—and I was true to my word. He beat me for the first time during his freshman or sophomore year, and I never played him again. My willingness to be humiliated is limited.

The Flanders Panel is good, but the Pérez-Reverte quotation at the beginning of this essay is from a different mystery—The Seville Communion. Because it involves ideas and issues that I am perpetually fascinated by, this story is my favorite of the four Pérez-Reverte mysteries I have read so far. The main character in The Seville Communion is Lorenzo Quart, a Jesuit priest sent from the Vatican to Seville charged with sorting out a complicated and tangled situation involving Our Lady of Tears, a historic but crumbling Catholic church built on land for which various constituencies have plans that do not include a church in which only a few dozen people worship per week.

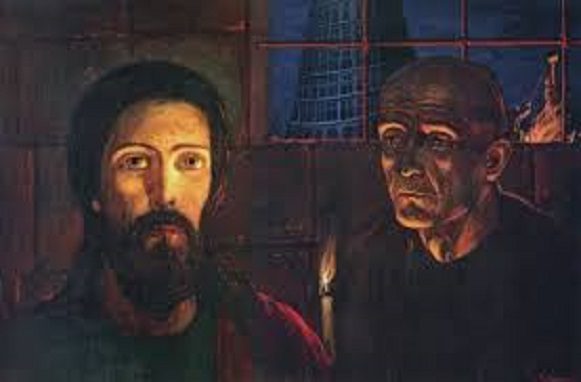

Father Quart considers himself to be a soldier in the Roman Catholic army rather than a priest; he is intelligent, effective, agnostic, and cynical. But he meets his match in Father Priamo Ferro, the aging priest in charge of the church in question. Quart expects Ferro to be an embodiment of everything Quart hates—old-style Catholicism with Latin masses for the benefit of a handful of elderly female parishioners. What he finds instead generates conversations reminiscent of another famous literary conversation set in Seville—Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor tale from The Brothers Karamazov.

Dostoevsky’s Inquisitor converses with Jesus, who has unexpectedly and inexplicably shown up in sixteenth-century Seville. Their wide-ranging conversation focuses on the impossibility of Jesus’ message of individual freedom, choice, and responsibility—the Inquisitor points out that the Catholic church has spent centuries repackaging Christianity into something that human beings want and can handle. The freedom proclaimed by Jesus is too demanding and makes people unhappy. Human beings prefer security and consolation to an unendurable freedom. All that human beings want is to be saved from the great anxiety and terrible agony they endure at present in making free decisions for themselves. In The Seville Communion, the conversations between Fathers Quart and Ferro focus on precisely why human beings need consolation and security in the first place.

Quart is surprised to find that Ferro, who appears to be an embodiment of traditional, faithful Catholicism, has not believed in the existence of God for some time; Ferro is convinced that not even the Pope believes in God any more. But this doesn’t matter. As Ferro tells Quart, the purpose of faith is

To reassure man confronted with the horror of his own solitude, death, and the void . . . Faith doesn’t even need the existence of God. It’s a blind leap into a pair of welcoming arms. It’s solace in the face of senseless fear and suffering. The child’s trust in the hand that leads out of darkness.

The greatest human fear? That nothing means anything. That life’s a bitch and then we die. As the Grand Inquisitor tells Jesus, the purpose of faith is to convince ourselves, in the face of contrary evidence, that somewhere, somehow, there is a purpose to it all. The church’s role is to facilitate this illusion. As Ferro explains, the challenge is

How to preserve, then, the message of life in a world that bears the seal of death? Man dies, he knows he will die, and also knows that, unlike kings, popes, and generals, he’ll leave no trace. He tells himself there must be something more. Otherwise, the universe is simply a joke in very poor taste; senseless chaos. So faith becomes a kind of hope, a solace.

In the great game of life, most of us are lonely pawns. Pawns are the most plentiful and least powerful pieces on a chessboard. Pawns can move only one square at a time, and only forward. It must often be tempting for a pawn to imagine that there is no point to the game, that other pieces with more options are the only ones that can make a difference, that perhaps the king who the pawn is assigned to defend does not even exist. And yet the pawn endures—until it is taken and removed from the board. No wonder we embrace stories that tell us otherwise, stories intended to convince us that there is something bigger going on in which each of us, often unwittingly and in ignorance, plays a part.

The Grand Inquisitor and Father Ferro have a point—there’s a lot to be said for exchanging the challenge of freedom and responsibility for the security of what Dostoevsky calls “miracle, mystery, and authority.” But to exchange freedom and responsibility for security and comfort, no matter how seductive, is to sacrifice both what makes us human and the heart of true faith. As Simon Critchley, in an essay focusing on the Grand Inquisitor story, writes:

It is the freedom of faith. It is the acceptance—submission to, even—a demand that both places a perhaps intolerable burden on the self, but which also energizes a movement of subjective conversion, to begin again . . . Faith hopes for grace . . . Such an experience of faith is not certainty . . . On this view, doubt is not the enemy of faith. On the contrary, it is certainty. If faith becomes certainty, then we have become seduced by the temptations of miracle, mystery, and authority . . . [Faith] is defined by an essential insecurity, tempered by doubt and defined by a radical experience of freedom.

In the midst of uncertainty and lack of information, each lonely pawn has a continual choice to make. Does my life mean anything? Can I make a difference? When considering these questions, it is worth remembering that even the lowly pawn, once in a while, gets to move one space diagonally and perhaps change the whole landscape of the game. True faith is a leap, but not into the security of collective conformity. Rather, it is a continuing commitment to and embrace of both freedom and responsibility–the choice to pursue that most elusive of goals: the meaning of my life.