![images[1]](http://wp.production.patheos.com/blogs/freelancechristianity/files/2012/09/images11.jpg) When I was growing up in northeastern Vermont, the Fairbanks Museum in St. Johnsbury was a favorite point of destination. It is an impressive stone structure, a small natural science and history museum, planetarium, and place to hang out all rolled into one. Admission was free for residents of St. Johnsbury, where my cousins lived, as well as for residents of neighboring towns, which included me. My cousins and I spent many Saturdays with nothing to do at the Fairbanks, followed, if we had any money, by a few strings of

When I was growing up in northeastern Vermont, the Fairbanks Museum in St. Johnsbury was a favorite point of destination. It is an impressive stone structure, a small natural science and history museum, planetarium, and place to hang out all rolled into one. Admission was free for residents of St. Johnsbury, where my cousins lived, as well as for residents of neighboring towns, which included me. My cousins and I spent many Saturdays with nothing to do at the Fairbanks, followed, if we had any money, by a few strings of  bowling at the alley just a few blocks farther down Main Street. Since the Fairbanks was also a favorite place for grade school classes to take their field trips (it was free, after all), I got to know the place very well.

bowling at the alley just a few blocks farther down Main Street. Since the Fairbanks was also a favorite place for grade school classes to take their field trips (it was free, after all), I got to know the place very well.

![pac_man_vs_pong[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2012/09/pac_man_vs_pong1.gif?w=150)

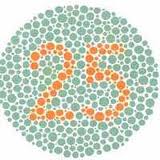

I t was in the basement of the Fairbanks Museum that I gained, for the first time, empirical evidence supporting what I had suspected for my whole life—I’m partially color-blind. In a glass display at the bottom of the basement stairs was a row of color test plates (I learned today from Wikipedia that they are called “Ishihara color test plates”), circles containing colored spots within which were embedded a figure, usually a number, made of spots with a slightly different color. People with normal color vision can see the number easily, but those with certain color deficiencies can’t. I couldn’t. My normal color-seeing companions could immediately see the “25” in the circle, while I only saw spots. I learned that I have red/green color deficiency—nobody’s perfect.

t was in the basement of the Fairbanks Museum that I gained, for the first time, empirical evidence supporting what I had suspected for my whole life—I’m partially color-blind. In a glass display at the bottom of the basement stairs was a row of color test plates (I learned today from Wikipedia that they are called “Ishihara color test plates”), circles containing colored spots within which were embedded a figure, usually a number, made of spots with a slightly different color. People with normal color vision can see the number easily, but those with certain color deficiencies can’t. I couldn’t. My normal color-seeing companions could immediately see the “25” in the circle, while I only saw spots. I learned that I have red/green color deficiency—nobody’s perfect.

Being color-blind has not turned out to be a big deal. I always ask Jeanne to endorse my clothing choices and especially to match a tie to a shirt when she’s home; when she’s not, I dress in safe colors, primarily blue, gray, black, red, yellow—anything that doesn’t require me to tell the difference between shades of green and brown, or various permutations of purple. Actually, purple turns out to be the biggest problem for this particular red/green colorblind person—go figure. But when I was a kid, my colorblindness was frequently a source of unwanted attention. My father and brother, for instance, entertained themselves by finding a house, a billboard, or car with the sort of color that I didn’t see as they did. “What color is that?” they would ask, and would laugh like hyenas when I got it wrong. When I finally started saying petulantly “I’m not playing that game anymore,” they laughed even harder.

Color-blindness, at least of the sort I have, is not a debilitating condition—it’s just good to know that I have it so that I can adjust accordingly. Far more important, I think, are the sorts of blindness that all of us are afflicted with, limitations so insidious that every one of is convinced that we see perfectly (even if no one else does). One of the continuing issues that I’ve grappled with over the past few years has to do with the importance of seeing, not just clearly, but differently. The natural human procedure is to view everything through filters and screens that tend to be invisible, yet distort everything that we see. A recent Sunday gospel provides a powerful example of the power of seeing differently. Jesus’ ministry of healing and teaching is in full swing. The crowds are so unrelenting that Jesus and the disciples do not even have time for a proper meal. J esus has a good idea—let’s get away to a deserted place and rest for a while. With that in mind, Jesus and his inner circle hop into their boat and sail on the Sea of Galilee to where they think they can have a bit of quality down time together. But word spreads so fast that a new crowd is waiting for them when they land. So they try it again, jumping in the boat and sailing away. But the masses are waiting for them wherever they land.

esus has a good idea—let’s get away to a deserted place and rest for a while. With that in mind, Jesus and his inner circle hop into their boat and sail on the Sea of Galilee to where they think they can have a bit of quality down time together. But word spreads so fast that a new crowd is waiting for them when they land. So they try it again, jumping in the boat and sailing away. But the masses are waiting for them wherever they land.

Put yourself in Jesus’ sandals—what do you see? I remember Andrew Lloyd Webber’s interpretation of a scene just like this in his 1970 rock opera “Jesus Christ Superstar.” Crowds of people in need of healing are swarming around Jesus demanding his attention, which he tries to provide. But for every person he touches, five more show up.  The crowd becomes larger and more insistent, grabbing at his clothes, blocking his way, surrounding him in a closer and tighter circle. Their musical chant increases in intensity and pitch; Jesus begins to sing “There’s too many of you, don’t push me, please don’t crowd me” in a high pitched wail above the cacophony. Finally he screams at the top of his lungs—“HEAL YOURSELVES!!!” and the stage goes black. Then one spotlight shines on Mary Magdalene as she soothingly sings “Try not to get worried, try not to turn on to problems that upset you; don’t you know everything’s all right, yes everything’s fine.”

The crowd becomes larger and more insistent, grabbing at his clothes, blocking his way, surrounding him in a closer and tighter circle. Their musical chant increases in intensity and pitch; Jesus begins to sing “There’s too many of you, don’t push me, please don’t crowd me” in a high pitched wail above the cacophony. Finally he screams at the top of his lungs—“HEAL YOURSELVES!!!” and the stage goes black. Then one spotlight shines on Mary Magdalene as she soothingly sings “Try not to get worried, try not to turn on to problems that upset you; don’t you know everything’s all right, yes everything’s fine.”

Webber’s imaginative score is brilliant because it is so real. Trust me; the reaction of Webber’s Jesus to the crowd is exactly what my reaction would have been, except I might have included an f-bomb or two. In Jesus’ sandals, I would have seen a mob seeking to suck me dry of everything I have to offer, treating me like a miracle-dispensing ATM instead of a human being who gets exhausted and needs to get his batteries recharged. And there is an element of that in Mark’s account—Jesus is trying (twice, no less) to get away from the crowds that are demanding more than he presently has to offer.

And that’s the beauty of the story. Because although Jesus wants and needs to be alone with his friends and rest, he ultimately does not run from the crowd—he sees them for what they are.  “He had compassion for them, because they were like sheep without a shepherd; and he began to teach them many things.” Yes Jesus was the Son of God and yes he perhaps had more to offer than we do, but his compassion for the crowd is not due to his divinity. It is due to his choosing to see differently, to get past the normal human self-centered filters and look at what is in front of him. He sees a need that he can address and addresses it, even though he’d rather be doing something else. Iris Murdoch defines love as “the extremely difficult realization that something other than oneself is real,” and Jesus’ compassionate gaze on the crowd is one of pure love.

“He had compassion for them, because they were like sheep without a shepherd; and he began to teach them many things.” Yes Jesus was the Son of God and yes he perhaps had more to offer than we do, but his compassion for the crowd is not due to his divinity. It is due to his choosing to see differently, to get past the normal human self-centered filters and look at what is in front of him. He sees a need that he can address and addresses it, even though he’d rather be doing something else. Iris Murdoch defines love as “the extremely difficult realization that something other than oneself is real,” and Jesus’ compassionate gaze on the crowd is one of pure love.

Color-blindness isn’t so bad. But other-blindness, the blindness that is part and parcel of being human, is. In John 14, Jesus promises that because he is going back to his Father and because of the coming of the Holy Spirit, we will do “greater works than these.” And although I don’t completely rule out the possibility of healings and other spectacular miracles today, these are not the works Jesus is talking about. Our greatest works will flow from our divinely energized ability to see things as they are, not as we would like them to be or as we wish they were, and to address the needs with unfiltered directness. Jesus looked at what was right in front of him with compassion. Let’s go and do likewise.