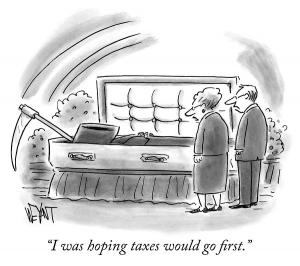

In a normal year, today would be everyone’s least favorite day of the year–Tax Day. One of the few things we can thank Covid-19 for is that we get an extra month to file this year; last year we got three extra months. But just like death, taxes are inevitable. According to a recent New Yorker cartoon, it’s an open question as to which is worse.

Permit me to state the obvious: No one likes paying taxes. I put off doing our taxes until no more than a week before the deadline each year, not because I need to wait that long to gather all of the necessary information, but because filing taxes is right up there with root canal as one of my favorite things. But I’m wondering today whether those of us who profess to be followers of Jesus should have this bad attitude about taxes. There is more about taxes in the gospels than we might choose to remember or talk about–none of it justifies hating having to pay them. As a matter of fact, there are reasons to believe that, if we take our faith commitments seriously, Christians should welcome the opportunity to pay taxes.

The purported author of the first gospel, Matthew, according to his own narrative was a tax collector when called by Jesus to be one of his disciples. Tax collectors in Jesus’ day had roughly the same reputation that people who work for the IRS do now—Jesus is frequently criticized for regularly hanging out with “tax collectors and sinners.”

There were various taxes to be paid, including an annual tax levied on males over nineteen years of age for the upkeep of the temple. Matthew tells a peculiar story about this tax; upon being approached while at Capernaum by the temple tax collectors about paying his fair share, Jesus sends Peter fishing, telling him that in the mouth of the first fish he catches “you will find a coin worth twice the temple tax. Give that to them for me and for you.” Would that satisfying the IRS were that easy, but the point is clear. Jesus paid his taxes.

By far the best known “Jesus and taxes” story is told in all of the gospels but John. This time the issue is not about temple taxes, but about paying taxes to the Emperor of the occupying Romans. The Pharisees intend to get Jesus in deep trouble with someone when they ask “Tell us, then what is your opinion: Is it lawful to pay the census tax to Caesar or not?” If Jesus says “no,” he will be in trouble with the Romans, and if he says “yes,” he will be in trouble with his fellow Jews, few of whom have any desire to pay taxes to Rome.

Jesus’ famous answer, of course, is “Give to Caesar what belongs to Caesar, and to God what belongs to God.” The Pharisees want to know if paying taxes to Caesar is “lawful”—Jesus essentially says “that depends on what law you are referring to.” As citizens of the world, Jesus and his followers are subject to whatever laws citizens are subject to—whether they like those laws or not. What is owed to God is calculated according to an entirely different standard and law—and, in this case at least, the two laws are not in conflict with each other.

I could say at this point that “thus endeth the lesson” on Jesus (and hence Christians) and taxes. There’s no basis upon which not to pay lawful taxes, but there’s also no reason to be happy about it. Not very illuminating and not very interesting. But I think there are other reasons that contemporary American Christians should not just put up with paying taxes. We should embrace the opportunity. Here’s why.

The strongest, most visceral source of resistance in the U.S. to paying taxes is the very idea of the government (or anyone) taking something that belongs to me without my permission. As any good capitalist will tell you, the wages I receive in payment for my labor belong to me. They are mine to do with as I see fit. But there is nothing more at odds with the heart of the Christian faith, more in conflict with the energy of the gospels, than the notion that anything, let alone my money, ultimately belongs to me.

The heart of Jesus is radical generosity and giving. Many Christians have turned this into tithing supplemented by charity—a rule that demands I give a small portion of what is mine away, followed by a suggestion that I should be occasionally generous—on my own terms and when I choose—with my time and what I own. Once I have followed the rules and given some of myself away, the rest belongs to me. But to follow Jesus is to recognize that everything I have is a gift to be given away. Every time a follower of Jesus is tempted to hold tightly to what she believes is “hers,” whenever a Christian resists letting go of what is “his,” even in the face of need that he can directly address, the radical openness and generosity of the gospels is violated.

The early Church father Ambrose is instructive on these matters. To Christians who seek to divide between what is “mine” and what is “yours,” Ambrose wrote that

It is the hungry man’s bread that you withhold, the naked man’s cloak that you store away, the money that you bury in the earth is the price of the poor man’s ransom and freedom.

What does any of this have to do with taxes? Without getting unnecessarily into the weeds of wasted tax dollars and money misdirected away from what they are intended to fund, I can at least learn a basic lesson from paying taxes. Some things are more important than I am.

Rather than begrudgingly parting with what really belongs to me every payday and every annual Tax Day simply because I know I will get into legal trouble if I don’t, what if I thought of paying taxes as an opportunity to practice cultivating a habit that we Americans find very difficult to even consider seriously—the habit of seeing the world with something other than myself at the center. Paying taxes can help me recognize that there are many people in need, many programs designed to improve the lives of everyone, that are more appropriate recipients of my money than my bank account. Paying taxes might remind me that occasionally what serves my own narrow interests is not best. Paying taxes forces me to admit that other people are at least as important, and maybe even more important, than I am.

These are tough lessons to learn, difficult habits to cultivate, for people raised to believe that individual interests are always more important than collective need, that competition trumps cooperation, and that absolutely nothing is more important than the right to do what I want, when I want, with what is mine. But these should not be difficult lessons for those who seek to follow Jesus to embrace. The habits of generosity, openness, and attention to those in need are central to what Christians claim to be. Tax Day should serve as an annual internal check on how we are doing.