As is the case with many of the things in my life, my knowledge of social media is both narrow and deep. I am active only on two social media platforms, but on those limited platforms I am very active. Any time I have wondered about something other than Facebook and Twitter, I ask my oldest son who, because of his work, is active across numerous social media platforms, whether I should try it out. He always tells me to stay away from whatever I am curious about. When I asked him about Instagram, for instance, Caleb said something along the lines of “there is absolutely no reason ever for you to be on Instagram, Dad.” I’m not sure if he was trying to protect me or himself from total embarrassment, but I took his advice to heart. I have never been on Instagram.

I claim that the reason I am on Facebook and Twitter is to use them as vehicles for my blog. This is completely true regarding Facebook, since I estimate that at least half of the thousands of readers who come to my blog in a given month get there through various Facebook sites. I cannot justify my frequent presence on Twitter similarly, though, since I have zero evidence that more than a person or two ever comes to any given blog post or essay in response to my tweeting it at them.

In truth, the only things I ever do on Twitter is talk sports trash (which has been far less available during Covid-19), or get involved with the daily political tweeting train wreck that happens 24-7. I can’t stop virtual rubbernecking on Twitter. Actually, it’s worse than rubbernecking. It’s like seeing a bad crash on the other side of the interstate, pulling onto the median, walking over to the accident, then telling those inside the car that only stupid people could ever find themselves in such a position, while they scream back that I am an effing moron who doesn’t deserve to exist.

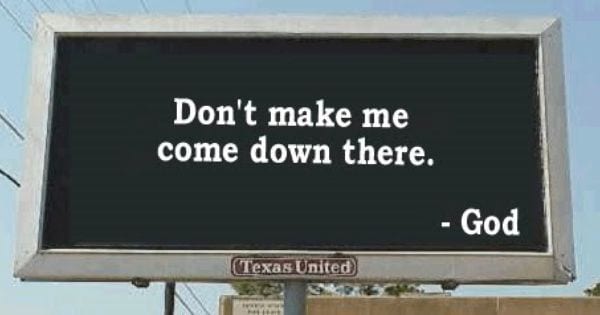

But there are a couple of Twitter feeds that I check regularly for real entertainment. One of them is simply called “God” (@TheTweetOfG0d). Imagine if the Creator of the Universe had a Twitter feed and occasionally tweeted some divine observations about what is going on these days. God has had any number of things to tweet, some insightful, almost all of them hilarious. But the most concerning was when God tweeted one day last summer that the divine patience was wearing thin.

Don’t Make Me Come Down There!

Oh my. That brought back a lot of memories, very few of them good.

In the religious world of my youth, we were obsessed with eschatology—”End Times”—beginning with the rapture and ending, after a whole bunch of bad stuff happening, with Jesus returning on a white horse with a sword in his hand in order to seriously kick ass and take names. “Jesus is coming back” was such a consistent theme in sermons, Sunday school, and conversations at home that I found myself looking over my shoulder most of the time. We sometimes made light of it, saying things like “Jesus is coming back . . . look busy!” or, when we smart ass kids were alone, “Jesus is coming back, and boy is he pissed!”

But bottom line, it was no laughing matter. The God I was taught to believe in was very much like God on Twitter—observant, engaged, and increasingly annoyed. That this God is also returning at some point was distressing, especially since I was also taught that my daily behavior had a great deal to do with how I would be treated during the “End Times.”

Advent begins soon, the beginning of a new liturgical year. Advent is about hope and anticipation, energies usually directed toward the Incarnation and the birth of Jesus. Advent texts, however, also directs our anticipation toward other future events. For instance, in the texts for the first Sunday of Advent in two weeks, Isaiah calls for divine intervention in a world that has run amuck—”O that you would tear open the heavens and come down, so that the mountains would quake at your presence”—and in Mark’s gospel, Jesus predicts that at some point in the future, an event no one can accurately predict, that’s precisely what will happen.

Then they will see the Son of Man coming in clouds with great power and glory . . . But about that day or hour no one knows . . . Beware, keep alert; for you do not know when the time will come. Therefore, keep awake—for you do not know when the master of the house will come, in the evening, or at midnight, or at cockcrow, or at dawn, or else he may find you asleep when he comes suddenly. Keep awake.

Texts such as these caused me many sleepless nights in my youth.

How would you live your life if you truly believed both that your choices and actions mattered to God and that God would be holding you accountable for them sometime in the not-too-distant future? Answers to such a question will be as unique and individual as human beings are. But we at least have in front of us one lived answer to the question in real time, something suggested by a friend on Facebook during the last week:

Live your life in such a way that millions of people in various cities across the globe will not break out in spontaneous demonstrations of joy at the news that you have been fired from your job.

That might seem to be an easy lift, but think about it. What if your daily life—your choices, attitudes, commitments, and actions—were publicized globally, so that everyone in the world could easily make judgments about you and how you conduct yourself?

The world we are currently living in is an odd mixture of apathy and heightened awareness, a world of “nothing matters” and “everything matters” all mixed together in a disturbing brew. It’s easy to imagine that nothing I do or say matters in the larger scheme of things, and perhaps they don’t. But imagining that what I do and say does matter from the perspective of what is greater than me helps to un-muddy the waters a bit. It’s a helpful exercise in gaining perspective, whether God is watching or not. After all, as my five-year-old son told me decades ago when explaining why he would never steal anything even if no one knew that he had done so: I would know.