We are all patchwork, and so shapeless and diverse in composition that each bit, each moment, plays its own game. And there is as much difference between us and ourselves as between us and others. Michel de Montaigne, Essais

I regularly tell my students that after more than thirty years of studying and teaching philosophy, I am convinced that the most interesting philosophical subject is a close to home as possible. The most fascinating philosophical topic is us. As the Psalmist writes, human beings are “fearfully and wonderfully made.” Sophocles describes us similarly in Antigone, describing humans as deinos, which means both “terrible” and “wondrous.” Think of “awful” and “awesome” and you’ll get the idea. Human beings are capable of both the best and the worst—often at the same time.

Montaigne continues his observation in the passage above about the patchwork nature of human beings by suggesting that “in view of the natural instability of our conduct and opinions, it has often seemed to me that even good authors are wrong to insist on fashioning a consistent and solid fabric out of us.” That hasn’t, however, stopped the best thinkers from trying over the centuries to do so. It also hasn’t stopped various attempts to reduce our fearful and wondrous complexity to rationally comprehensible and manageable features. What if human beings learned to always choose and act in their best interests? What if human beings knew what was profitable and best for them individually and collectively—and then acted on that knowledge? Every time?

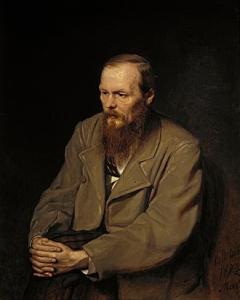

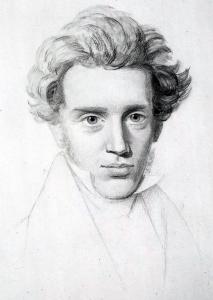

Soren Kierkegaard and Fyodor Dostoevsky, authors who are the primary focus during the first few weeks of the new “Faith and Doubt” colloquium I am team-teaching with a colleague from the PoliSci department, explored these and related questions during the 19th century, at a time when advances in science and technology raised the possibility of human perfectibility as a legitimate vision for the future. In Notes from Underground, Dostoevsky’s unnamed Underground Man considers such hopes to be both naïve and misdirected.

But these are all golden dreams. Who first announced, who was the first to proclaim that man does badly only because he doesn’t know his real interests; and that were he to be enlightened, were his eyes to be opened to his real, normal interests, man would immediately become good and noble, because . . . he would see his real profit precisely in the good? . . . Oh, the babe! Oh, the pure, innocent child!

But these are all golden dreams. Who first announced, who was the first to proclaim that man does badly only because he doesn’t know his real interests; and that were he to be enlightened, were his eyes to be opened to his real, normal interests, man would immediately become good and noble, because . . . he would see his real profit precisely in the good? . . . Oh, the babe! Oh, the pure, innocent child!

Everyone knows that it is possible to know what is in their best interest and still do something else—simply because each of us has done this.

What is to be done with the millions of facts testifying to how people knowingly, that is, fully understanding their real profit, would put it in second place and throw themselves onto another path . . . What if it so happens that on occasion man’s profit not only may but precisely must consist in sometimes wishing what is bad for himself, and not what is profitable?

What the Underground Man is describing is both definitive of being human and the source of great trouble.

In The Sickness unto Death, Søren Kierkegaard considers the same human dynamic as Dostoevsky, but through a different lens. Kierkegaard begins his discussion with Socrates’ famous claim that “sin (evil) is ignorance” and that “to know the good is to do the good.” In other words, Socrates proposed, the source of human moral failings and capacity to do evil is lack of knowledge. More than two millennia before the 19th century, Socrates is agreeing with those who imagine the perfectibility of human nature—as we become more knowledgeable, we will naturally become morally better. Kierkegaard, an astute observer of human nature, isn’t buying it. There is a difference between lack hof knowledge (mere ignorance) and willful ignorance, acting as if one does not have knowledge that one actually has.

After providing several examples—familiar to all—of people who demonstrate their knowledge and support of A publicly then immediately do not-A, Kierkegaard notes that Socrates’ definition fails to take into consideration that human beings are more than rational beings. “What determinant is it then that Socrates lacks?” Kierkegaard asks. “It is will, defiant will.” What is it that causes people to act against their interests, to behave badly, to act immorally? It has nothing to do with lack of knowledge and everything to do with the power of the will. I act contrary to what I know is best and right because I can. Not because I mistake error for truth, but simply because I want to. What is to be done with such a creature?

In Kierkegaard’s estimation, this tension between reason and will cannot be eliminated—it is part of what we are. Any attempt to improve humanity simply through increased knowledge will spectacularly fail—history itself has over and over shown this to be true. The genius of Christianity, Kierkegaard believes, is that embedded in its seminal story is both a truthful description of and a supernatural cure for what ails human beings.

In Kierkegaard’s estimation, this tension between reason and will cannot be eliminated—it is part of what we are. Any attempt to improve humanity simply through increased knowledge will spectacularly fail—history itself has over and over shown this to be true. The genius of Christianity, Kierkegaard believes, is that embedded in its seminal story is both a truthful description of and a supernatural cure for what ails human beings.

There must be a revelation from God in order to instruct man as to what sin is, that sin does not consist in the fact that man has not understood what is right, but in the fact that he will not understand it, and in the fact that he will not do it . . . Sin lies in the will, not in the intellect; and this corruption of the will goes well beyond the consciousness of the individual.

Call it “original sin,” if you want, or as John Henry Newman called it, “some aboriginal calamity.” The Christian insight is that human nature is fundamentally flawed and cannot be perfected without divine help. And that help, of course, is the whole point of the Incarnation, Crucifixion, and Resurrection.

The Pandora’s box opened by the simple observation that human beings regularly choose and act in ways contrary to what they know is in their interest and/or what they know is right simply because they can is a source of endless debate in psychological, philosophical, and theological circles. Many of us have been told from our youth that this is a defect to be addressed, an illness to be cured, a problem to be solved. Seldom do we ever stop and ask whether “original sin” or “weakness of the will” is something that we should seek to cure at all. Kierkegaard believes that his analysis directs us toward the only possible solution, but Dostoevsky’s Underground Man isn’t so sure that this is something we should seek to cure or eliminate at all.

What if, Dostoevsky asks, seeking to perfect human beings is actually an attempt to eliminate something that is definitive of being human?

You want to make man unlearn his old habits, and to correct his will in conformity with the demands of science and common sense . . . What makes you conclude that man’s wanting so necessarily needs to be corrected?

Imagine a person who always chooses what is best and has eliminated even the possibility of doing otherwise? The Underground Man suggests that such a person has become a “piano key,” fine-tuned to do only one thing (even if it is the profitable or right thing), and is no longer fully human.

Why are you so certainly convinced that not to go against real, normal profits, guaranteed by the arguments of reason and arithmetic, is indeed always profitable for man and is a law for the whole of mankind? So far, it’s still just your supposition. Suppose it is a law of logic, but perhaps not of mankind at all.

Consider the classic “original sin” parable—Adam and Even in the Garden of Eden. Their choice to act against their interests as God defined them and to eat of the forbidden fruit was an act of will, not of knowledge. Their choice illustrates the human ability to choose “otherwise,” to choose against our best knowledge—an ability that we call “free will” and honor as perhaps what makes us most different from and better than every other created thing. Perhaps this is what the Psalmist means by “fearfully and wonderfully made.”

The tension between intellect and will, just as the tension between us and what is greater than us, is foundationally definitive of what it means to be human. We should think carefully about any attempts, from scientific to theological, to either remove, correct, or cure what we are. After all, as the Underground Man reminds us, “the whole human enterprise seems indeed to consist in man’s proving to himself every moment that he is a man and not a piano key.”