In my General Ethics course, we just completed a unit called “Does God have anything to do with ethics?” last week. One of the essays we considered was William Irwin’s “God is a Question, Not an Answer”; it raised issues that parallel those raised by the contrast between Cromwell and More. Irwin admits that “people who claim certainty about God worry me, both those who believe and those who don’t believe,” since, in his estimation,

God is a question, not an answer . . . The question is permanent; answers are temporary. I live in the question . . . Dwelling in a state of doubt, uncertainty and openness about the existence of God marks an honest approach to the question . . . Anyone who does not occasionally worry that she is wrong about the existence or nonexistence of God most likely has a fraudulent belief.

Irwin concludes his essay with this from Thomas Merton:

Faith is a decision, a judgment that is fully and deliberately taken in the light of a truth that cannot be proven—it is not merely the acceptance of a decision that has been made by somebody else.

These same matters arise throughout fiction, including in a long-awaited conclusion to an honored historical fiction trilogy that was just published.

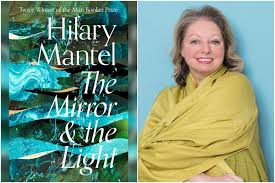

Lovers of great historical fiction (I am one of them) have been anxiously waiting for several years for the third installment in Hilary Mantel’s honored trilogy that immerses us into the world of Henry VIII as seen through the eyes of his consigliere Thomas Cromwell. Wolf Hall (2009) and Bring up the Bodies (2012), the first two parts of the trilogy, each won the Man Booker Prize (the British version of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction). After what seemed an extraordinarily long wait for dedicated lovers of Mantel’s work, The Mirror and the Light, the third installment in the trilogy, was published a few weeks ago, a welcome gift for millions of people who suddenly find themselves with more reading time on their hands than usual.

Early in Wolf Hall, Cromwell provides us with a flashback to when he was a young star in Cardinal Wolsey’s orbit, a firmament containing another, brighter star—Thomas More—who in Mantel’s treatment becomes one of Cromwell’s opponents and competitors for the attention of the great and powerful. But more importantly, Cromwell reveals a fundamental difference between him and More that raises issues transcending this particular story:

He [Cromwell] never sees More . . . without wanting to ask him, what’s wrong with you? Or what’s wrong with me? Why does everything you know, and everything you’ve learned, confirm you in what you believed before? Whereas in my case, what I grew up with, and what I thought I believed, is chipped away a little and a little, a fragment then a piece and then a piece more. With every month that passes, the corners are knocked off the certainties of this world: and the next world too. Show me where it says, in the Bible, “purgatory.” Show me where it says “relics, monks, nuns.” Show me where it says “Pope.”

Or, someone might add, show me where it says “liturgy” or “dogma” or any number of other things that are staples of Christian tradition even outside Catholicism. I have no idea whether Mantel’s characterization of Cromwell and More is accurate (neither does she, for that matter), but I am so strongly aligned by nature with fictional Cromwell in this passage that I share his utter astonishment with the fictional Mores among us. Wolf Hall is set during the early decades of the sixteenth century when the revolutionary impact of the Protestant Reformation is already making itself known in England. Thomas More is the epitome of religious certainty, imagined by Mantel as a vigorous, devout, hair-shirt-wearing and frequently inflexible defender of Catholic orthodoxy.

Although Cromwell rises to influence as the right-hand man of the powerful Cardinal Wolsey, he is far more comfortable with situational flexibility than with pre-established beliefs and principles. When Wolsey falls from grace because of his failure to facilitate the king’s desire to divorce Catherine of Aragon in order to marry Anne Boleyn, Cromwell’s ability to quickly adjust to changing circumstances and maneuver creatively brings him into the king’s inner circle. But he always keeps the Mores of his world in view, simultaneously envious and wary of anyone’s unflinching commitment to principle.

I often find myself inadvertently dividing my fellow human beings into various categories (introvert/extrovert, high-maintenance/low-maintenance, Platonic/Aristotelian, hedgehog/fox, and more); Cromwell/More is another important distinction, especially when religious belief is under discussion. The older I get, the more Cromwellian I become, finding that even my most fixed beliefs not only are regularly under scrutiny, but that constant adjustment and change is a symptom of a healthy faith. Christian Wiman puts this insight better than anyone I’ve read:

It is why every single expression of faith is provisional—because life carries us always forward to a place where the faith we’d fought so hard to articulate to ourselves must now be reformulated, and because faith in God is, finally, faith in change.

I am frequently reminded in a number of ways by various Mores that a Cromwellian embrace of change is dangerous in that it supposedly leads to the brink of the worst of all abysses, a relativistic world with no absolutes and no fixed points. I admit that it can be disconcerting to find that one’s most reliable cornerstones have crumbled or shifted, but I have learned to find stability in commitment rather than in content. Within the well-defined banks of commitment to what is greater than us, the river of faith sometimes flows swiftly, sometimes pools stagnantly, and always offers the opportunity to explore uncharted waters. The terrain of commitment looks very different from various vantage points, and in my experience seldom provides confirmation of what I have believed in the past without change and without remainder.

I remember several years ago that I came across one of John Shelby Spong’s books in Borders with the provocative title Why Christianity Must Change or Die. I read the book and found that the changes that Spong, the liberal retired Episcopal bishop of New Jersey was calling for were not changes I was willing to make then—or now. But I fully resonate with the energy of his book’s title. The Christian faith that I profess has not only changed greatly over the past several years (and promises to change even more going forward), but the Christianity I was taught in my youth would have died long ago if it had not changed. And this is as it should be. As James Carse writes,

This is Christianity’s strongest feature: it tirelessly provokes its members to object to prevailing doctrines without having to abandon the faith . . . Neither Christianity nor any of the great religions has ever been able to successfully erect barriers against the dreaded barbarian incursions of fresh ideas.

One of the things I’ve learned over the past few years is to stop criticizing or belittling those who build their belief systems in the manner of More, shaping all new experiences and information in the image of their most fixed and unchanging commitments. There are a number of Mores among my friends and family, and I’ve learned not only to appreciate them (usually), but find myself occasionally envying them. But at heart I’m happy being Cromwell as I watch the corners get knocked off my certainties.