The best argument in the world won’t change a person’s mind. The only thing that can do that is a good story. Richard Powers

Richard Powers is one of my favorite novelists, perhaps the best living novelist that most people have either never heard of or haven’t read if they have heard of him. His latest novel, just out last week, is Bewilderment–I started it a couple of days ago. I’m not sure if I like it yet, but that’s not unusual for a Powers novel. He makes the reader work and think, often more than the reader might be prepared or willing to do. But the effort is always well rewarded. The passage quoted above is from The Overstory, his 2018 novel that won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. It will always have a special place in my memory because it was the novel I was reading when Jeanne and I were in Scotland for 10 days in the summer of 2018. One of the best novels I’d read in years, along with the most beautiful place I’ve ever visited, along with the most beautiful person I know. It doesn’t any better than that.

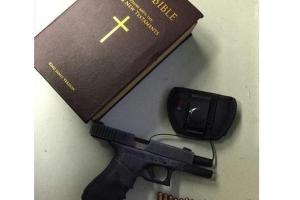

I run into issues related to storytelling all the time on this blog. Although the name of the blog is “Freelance Christianity,” and it is published on Patheos’ “Progressive Christian” channel, I regularly attract comments from readers who do not fit those categories by any stretch of the imagination.  Occasionally, someone using arguments and language I recognize from my evangelical Protestant upbringing will respond to my “liberal” or “non-Christian” ideas by weaponizing the Bible and seeking to beat me up with it. Such people usually are surprised to find that I am perfectly capable of playing that game as well as or better than they do. I was taught to use the Bible as a weapon in my youth, and I was very good at it.

Occasionally, someone using arguments and language I recognize from my evangelical Protestant upbringing will respond to my “liberal” or “non-Christian” ideas by weaponizing the Bible and seeking to beat me up with it. Such people usually are surprised to find that I am perfectly capable of playing that game as well as or better than they do. I was taught to use the Bible as a weapon in my youth, and I was very good at it.

More often, though, the critical comments come from the other end of the belief-in-God spectrum, from professed atheists who push back against whatever I’ve written because, although “progressive” on the spectrum of Christian belief, I have failed to realize that any version of Christian faith, or of any religious commitment for that matter, is little more than childish delusion. “Religions are arguments about whose imaginary friend is more powerful,” “God is just a fictional character—don’t most people grow out of their childish attachment to fairy tales?” I take these comments seriously, as I tend far more toward doubt and uncertainty in my faith than certainty and conviction. As for this business of God just being part of a story we tell ourselves, I respond “You’re absolutely right. God is just a story—and so are we, for that matter.”

In the Preface to The Gates of the Forest, Elie Wiesel captures this idea beautifully by . . . telling a story. In an old Hasidic tale, a series of rabbinical leaders each sought to follow a three-step ritual for accomplishing the rescue of his respective community through a miracle. The founder of the tradition was Rabbi Israel Baal Shem-Tovand; the three steps were to go to a specific area of a forest to meditate, say a specific prayer, and light a fire. Unfortunately, each of the subsequent leaders in turn forgot a step of the ritual that had been passed on to him. Maggid of Mezeritch remembered two of the three steps, Rabbi Moshe-leib of Sasov knew one of the two steps passed on to him, but Rabbi Israel of Rizhin couldn’t even remember the single step that he had been given. The rabbi confesses to a young listener that he’s old, his memory is failing him, and all he can do is tell stories. But, the rabbi concludes, “It is sufficient. For God made man because He loves stories.” Just remembering the story about the tradition was, as the rabbi hoped, sufficient for obtaining the needed miracle.

Several years ago, when I first read Kathleen Norris’ definition of “myth” in Amazing Grace as “a story that you know must be true the first time you hear it,” I smiled. I knew this definition to be true the first time I read it. In ethics classes with nineteen to twenty-one-year-olds who are predominantly survivors of twelve years of parochial education, I lean heavily on Alasdair MacIntyre’s insight that we human beings are “story telling animals”—we understand ourselves and each other by telling stories. Through the stories we tell, we make sense of our past and do our best to recreate the world by telling better and better stories projected into the future. We are lived stories, in the middle of a “never-ending story” with themes and characters that we catch only brief glimpses of.

The notion of identities and truths established through stories rather than anchored in verifiable facts runs counter to what many of us have been taught concerning the nature of truth. Facts, evidence, logical arguments, and so on are the tools of the trade for anyone seeking to build their reality on a reliable foundation rather than the shifting sands of fictions and myths. Logic and facts are, presumably, my tools of the trade when introducing students to the discipline of philosophy.

But I have discovered over many years in the classroom that narratives and stories are far more effective when introducing new and sometimes controversial ideas than logical precision. Returning to what a character in Richard Powers’ The Overstory says, “the best argument in the world won’t change a person’s mind. The only thing that can do that is a good story.”

There is a reason that the Bible contains very little argumentation and logical reasoning concerning the nature and existence of the divine, while filled from cover to cover with stories of all sorts. The authors and compilers of the sacred text understood that human beings resonate deeply with narratives and stories, tending to construct logical arguments after the fact to support the stories that have been most influential and life-affirming.

Flannery O’Connor, one of the most spiritual authors the United States has ever produced, wrote in Mystery and Manners that “a story is a way to say something that can’t be said any other way, and it takes every word in the story to say what the meaning is. You tell a story because a statement would be inadequate. When anybody asks what a story is about, the only proper thing is to tell them to read the story.”

Over the years, Jeanne and I often have often had our best conversations while sitting at a bar (we usually prefer the bar to a table); our approaches to engaging with the divine and things of the spirit are so different that we almost always engage in conversation about who and what God might be through stories, either our own or those we have read recently. During a pred-Covid conversation at the local watering hole, I once reminded Jeanne of something I have written and said on occasion over the past several years: “The best proof for the existence of God is a changed life.” My inspiration for this idea is the story of the once-blind man in the gospels who is challenged to respond to the charge that the man who healed him is a sinner: “Whether he is a sinner or not, I do not know. But this I do know—I was blind, and now I see.”

In other words, don’t bore me with doctrine, dogma, or proofs—I have a story that can’t be easily dismissed. With this in mind, I added that “I guess, then, that the best proof for the existence of God is me.” And you. And anyone who has a story to tell that involves that most influential and elusive of all fictional characters—God. Everything we are is a story of our own telling—choosing to place the divine in the middle of it changes everything.