Classes begin soon and I am coming slowly to the conclusion that my summer reading needs to shift from the Scandinavian-authored mysteries I have been immersed in since late May (thirteen down and counting) slowly toward books related to upcoming courses. In the spring I will be team-teaching a colloquium with a colleague from the history department entitled “Markets and Morality.”  As is always the case when teaching with someone from another discipline, I have a ton of books to read for the first time (as does she—just not the same ones). I have started with Nicholas Wapshott’s Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics. Economics is not only not my strong suit but is also high on my list of boring things, so it has taken several dozen pages to sort out what’s at stake in the early twentieth century debate between the theories of John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich von Hayek. Then I read this morning that “while Keynes, who was not without a large ego himself, was so confident he often changed his mind and admitted his faults, Hayek’s stance was based on absolute certainty that he was right in every particular.” “Aha!” I thought, “Keynes was a fox and Hayek was a hedgehog. That explains a lot.” This revelation will also be helpful going forward because I have learned that one of the most important things to find out about an academic is whether s/he is a hedgehog or a fox.

As is always the case when teaching with someone from another discipline, I have a ton of books to read for the first time (as does she—just not the same ones). I have started with Nicholas Wapshott’s Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics. Economics is not only not my strong suit but is also high on my list of boring things, so it has taken several dozen pages to sort out what’s at stake in the early twentieth century debate between the theories of John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich von Hayek. Then I read this morning that “while Keynes, who was not without a large ego himself, was so confident he often changed his mind and admitted his faults, Hayek’s stance was based on absolute certainty that he was right in every particular.” “Aha!” I thought, “Keynes was a fox and Hayek was a hedgehog. That explains a lot.” This revelation will also be helpful going forward because I have learned that one of the most important things to find out about an academic is whether s/he is a hedgehog or a fox.

I wrote a bit over a year ago in this blog about the hedgehog/fox distinction and how it can be a useful tool in both self-knowledge and understanding where others are coming from.

I wrote a bit over a year ago in this blog about the hedgehog/fox distinction and how it can be a useful tool in both self-knowledge and understanding where others are coming from.

When orienting students for the first time to the important differences between Plato, who is considered by many to be the greatest philosopher in the Western tradition, and his star pupil Aristotle (who gets my own “best ever” vote), I introduce the hedgehog/fox distinction first for orientation purposes. Plato is the quintessential hedgehog, an eloquent constructor of large metaphysical frameworks and scaffolding within which the details of human experience are to be sorted.

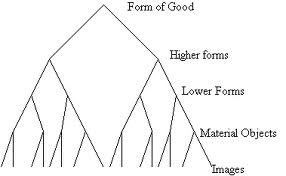

When orienting students for the first time to the important differences between Plato, who is considered by many to be the greatest philosopher in the Western tradition, and his star pupil Aristotle (who gets my own “best ever” vote), I introduce the hedgehog/fox distinction first for orientation purposes. Plato is the quintessential hedgehog, an eloquent constructor of large metaphysical frameworks and scaffolding within which the details of human experience are to be sorted.  As all hedgehogs, Plato is a “top-down” thinker, obsessed with certainty and Truth with a capital “T”. His realm of the Forms, silent and unchanging in their pristine and solemn beauty, provides a home for the equally beautiful human soul as well as a framework within which the mutable, ever-changing and not-so-beautiful (for Plato, at least) details of our daily experience are to be understood and situated. These details point toward the Forms, just as “truths” point toward the “Truth”—it’s a powerfully attractive model of reality. For hedgehogs, at least.

As all hedgehogs, Plato is a “top-down” thinker, obsessed with certainty and Truth with a capital “T”. His realm of the Forms, silent and unchanging in their pristine and solemn beauty, provides a home for the equally beautiful human soul as well as a framework within which the mutable, ever-changing and not-so-beautiful (for Plato, at least) details of our daily experience are to be understood and situated. These details point toward the Forms, just as “truths” point toward the “Truth”—it’s a powerfully attractive model of reality. For hedgehogs, at least.

In his Metaphysics, Aristotle spends the first several chapters providing, in a shot-gun manner, all of the reasons he can think of why Plato’s Theory of Forms is the stupidest theory any one has ever come up with and why no one should believe it. Why? Because Aristotle is a fox, as dedicated to foxiness as Plato is dedicated to hedgehogery, and foxes have little patience for the detached-from-reality otherworldly musings of hedgehogs. Foxes build their understanding of the world from the bottom up; obsessed with details, foxes cobble together frameworks and structures of understanding only after spending a great deal of time collecting experiential data. Theories serve the details for foxes, just as details and facts bow to theoretical constructs for hedgehogs. A simple comparative example might help.

In his Metaphysics, Aristotle spends the first several chapters providing, in a shot-gun manner, all of the reasons he can think of why Plato’s Theory of Forms is the stupidest theory any one has ever come up with and why no one should believe it. Why? Because Aristotle is a fox, as dedicated to foxiness as Plato is dedicated to hedgehogery, and foxes have little patience for the detached-from-reality otherworldly musings of hedgehogs. Foxes build their understanding of the world from the bottom up; obsessed with details, foxes cobble together frameworks and structures of understanding only after spending a great deal of time collecting experiential data. Theories serve the details for foxes, just as details and facts bow to theoretical constructs for hedgehogs. A simple comparative example might help.

In ancient Greek philosophy, the study of how individual human beings should behave (ethics) and the science of how to best form and administrate human communities (politics) were the same activity—both Plato and Aristotle contributed brilliant insights to these foundational investigations. In the Republic, arguably Plato’s greatest work, we encounter Socrates (usually the main character in Plato’s dialogues) and several of his friends and followers discussing “justice” at length. The angle they take on the question “What is justice?” is to consider “What would a just polis look like?” Polis refers to the small Greek city/states of Plato’s world—from this word we get terms like “politics,” “politician,” etc. The strategy is to discuss matters from broad questions such as virtue to detailed ones such what will the class structure of the imaginary perfectly just polis be theoretically without reference to communities that actually exist. When toward the end of the Republic someone asks Socrates “Do you think such a polis will ever exist in reality?” he answers “Probably not. But that’s okay—the model we have created is a valuable touchstone.”

In ancient Greek philosophy, the study of how individual human beings should behave (ethics) and the science of how to best form and administrate human communities (politics) were the same activity—both Plato and Aristotle contributed brilliant insights to these foundational investigations. In the Republic, arguably Plato’s greatest work, we encounter Socrates (usually the main character in Plato’s dialogues) and several of his friends and followers discussing “justice” at length. The angle they take on the question “What is justice?” is to consider “What would a just polis look like?” Polis refers to the small Greek city/states of Plato’s world—from this word we get terms like “politics,” “politician,” etc. The strategy is to discuss matters from broad questions such as virtue to detailed ones such what will the class structure of the imaginary perfectly just polis be theoretically without reference to communities that actually exist. When toward the end of the Republic someone asks Socrates “Do you think such a polis will ever exist in reality?” he answers “Probably not. But that’s okay—the model we have created is a valuable touchstone.”

When Aristotle begins investigating similar issues a few decades later, his approach is radically different. The first several chapters of his Politics are a detailed and wide-ranging account of the various ways in which a number of city-states scattered across the Greek peninsula are actually organized politically.  In other words, Aristotle starts by gathering facts and making observations rather than with the constructing of organizational frameworks. Academics will recognize Aristotle’s plan immediately—he has sent dozens of grad students from his educational institution “The Lyceum” out into the world to gather relevant data, data that they will bring back to Athens and help Aristotle collate into a comprehensive report on the state of political structures in the Greek polis—a report in which they might get mentioned in a footnote. And it is this report that will be the jumping off point for Aristotle’s informed thinking about how a polis should be organized. Let theory be informed by reality, says the fox, rather than reality shaped by theory as the hedgehogs prefer.

In other words, Aristotle starts by gathering facts and making observations rather than with the constructing of organizational frameworks. Academics will recognize Aristotle’s plan immediately—he has sent dozens of grad students from his educational institution “The Lyceum” out into the world to gather relevant data, data that they will bring back to Athens and help Aristotle collate into a comprehensive report on the state of political structures in the Greek polis—a report in which they might get mentioned in a footnote. And it is this report that will be the jumping off point for Aristotle’s informed thinking about how a polis should be organized. Let theory be informed by reality, says the fox, rather than reality shaped by theory as the hedgehogs prefer.

Which strategy is better—the hedgehog’s or the fox’s? It is probably clear from this discussion, and has become crystal clear over the two years of this blog’s existence, to any reader that I am a dedicated fox. But in truth, neither is intrinsically better or worse than the other; rather, they are fundamentally different strategies that human beings use as we try to understand the world and our place in it. And each of us has either a dominant hedgehog or fox lurking inside, often making it difficult to get on the same page with colleagues who have a different animal than mine hanging around. I have found this distinction to be very useful over the past few years. The coming academic year is my last as director of the interdisciplinary program that I have been in charge of since summer 2011; over the past three years, as faculty rotate in and out of the program, I have tried to lead, cajole, seduce and force over one hundred faculty through the early stages of the transition from an old version of the program into a new and quite different version. I’ve found that herding hedgehogs is quite different from herding foxes.

I have found this distinction to be very useful over the past few years. The coming academic year is my last as director of the interdisciplinary program that I have been in charge of since summer 2011; over the past three years, as faculty rotate in and out of the program, I have tried to lead, cajole, seduce and force over one hundred faculty through the early stages of the transition from an old version of the program into a new and quite different version. I’ve found that herding hedgehogs is quite different from herding foxes.

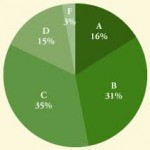

Take any issue—grade distribution, for instance. In any given semester, there are 18-20 different teams of three faculty teaching 100 or more students in each section; the program I inherited had no policies (formal or informal) related to grade distribution. In other words, as in other areas of the program, the foxes had been running unsupervised in the den for a long time. As a result the average grades from team to team at the end of each semester varied wildly, giving rise to warranted cries of “UNJUST” from students in the “tough” sections, lack of respect for this core program from faculty and other constituencies on campus, and a general feeling of suspicion and finger-pointing among those teaching in the program trenches. What to do?

Take any issue—grade distribution, for instance. In any given semester, there are 18-20 different teams of three faculty teaching 100 or more students in each section; the program I inherited had no policies (formal or informal) related to grade distribution. In other words, as in other areas of the program, the foxes had been running unsupervised in the den for a long time. As a result the average grades from team to team at the end of each semester varied wildly, giving rise to warranted cries of “UNJUST” from students in the “tough” sections, lack of respect for this core program from faculty and other constituencies on campus, and a general feeling of suspicion and finger-pointing among those teaching in the program trenches. What to do?

The hedgehogs insisted “we need firm and enforceable policies to get the outliers in line!” The foxes countered “any attempt to force grading policies from the top down will be a violation of our academic freedom!” As a dedicated fox who has to summon my few hedgehog abilities when trying to get people to do something, I knew that some sort of policies were needed—so how do policies get established without imposition? And the game was on—over several semesters of debate, crabbiness, subcommittees, drafts, and angst, we came tentatively to a document that was successfully sold to the faculty as an “informal guideline” for people to refer to going forward (if they chose). “This needs to be a policy that everyone has to follow!” yelled the hedgehogs. “This violates my academic freedom and desire to do whatever I want without recourse!” shouted the foxes. And so it goes.

As a dedicated fox who has to summon my few hedgehog abilities when trying to get people to do something, I knew that some sort of policies were needed—so how do policies get established without imposition? And the game was on—over several semesters of debate, crabbiness, subcommittees, drafts, and angst, we came tentatively to a document that was successfully sold to the faculty as an “informal guideline” for people to refer to going forward (if they chose). “This needs to be a policy that everyone has to follow!” yelled the hedgehogs. “This violates my academic freedom and desire to do whatever I want without recourse!” shouted the foxes. And so it goes.

Hedgehogs and foxes can learn to live in harmony—but only when they recognize that the world would be a vastly different place without both structure and freedom, both Truth and the little truths we encounter every day. Hedgehogs and foxes can even survive in long-term relationships with each other, but the offspring are a problem. Who knows what you’ll get from a foxhog?