This morning I am in the middle of a writer’s conference hosted by an ecumenical institute on the campus of St. John’s University in Collegeville, Minnesota, a place that over the past several years has become very meaningful to me as a place of peace, joy, and spiritual growth. As I sit in a lovely garden just across the way from the striking and looming presence of St. John’s Abbey, listening to its booming bells every quarter hour, I am reminded of a simple act of acceptance that was offered to me while I was here for the first time nine years ago on sabbatical. For me it has become a example of grace and love.

I have spent the last thirty years of my life, first as a student, then as a professor, as a non-Catholic in Catholic higher education. Accordingly, the issue of receiving Eucharist in a Catholic church has arisen on a regular basis. The official stance of the Catholic authorities, of course, is that non-Catholic folks like me are not welcome. When I was hired twenty-four years ago at my current Catholic college in New England, I asked the chair of the department that had just hired me, a Dominican sister, about what would happen if I as a non-Catholic went for communion at the chapel on campus. She replied with what I have come to recognize as a typical response on this matter: “I would have no trouble with it myself, but there are some on campus who probably would.” Given that those “some” undoubtedly included a few of the geezer Dominican priests in my new philosophy department, I decided that discretion was the greater part of valor and chose not to try it out. I never have received communion on campus in twenty-four years.

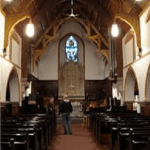

And that’s been fine. I’ve even made a point of attending mass once in a while in our main campus chapel and being one of the handful of people among hundreds not to go to communion. Given that many students show up on campus unaware that “non-Catholic Christian” is not an oxymoron, it’s a good “show-and-tell” moment. But the issue arose unexpectedly nine years ago when, while on sabbatical for four months where I am now at this writer’s conference, I found myself at daily prayers several times a day with a bunch of Benedictine monks. During those months I was experiencing a great deal of internal spring cleaning and scouring; my spirit was reviving and I was discovering inner resources I had been unaware of my whole life. As I gradually awakened to a new perspective, I realized that not sharing communion with these new Benedictine friends was becoming a problem.

One Saturday at dinner I asked one of the older monks, a physicist who had taught at the university for decades before his retirement a few years earlier in his middle seventies, what I should do. “Wilfred, I would like to receive communion at the Abbey,” I said, “but I’m not Catholic and I know that it’s against the rules for me to receive. What do you think?” “I’ll tell you what Kilian (an even older monk at the next table) always says,” Wilfred replied. “Our policy is ‘don’t ask, don’t tell.’” “But I just told you.” “And I forgot what you said.” The next day I queued up to receive communion after several weeks of sitting in the pew while others went to the front. “The body of Christ,” the Abbot said to me with a huge smile as he held the host in front of me. “Welcome.” Over the past nine years I have returned to the Abbey on many occasions, usually unannounced. Each time after the first morning, noon, or evening prayer I attend, the Abbot seeks me out and gives me a big hug, just as he did last Thursday morning after morning prayer. “Welcome home,” he says. That’s exactly how it feels.

In the middle of the sixteenth century, as his French countrymen and women were swept up into the violent storm of the Wars of Religion that followed in the wake of the Protestant Reformation, Michel de Montaigne had a simple observation to make about our ludicrous human pretensions to know the mind of God. As Protestants and Catholics regularly killed each other in the name of orthodoxy and right worship, Montaigne wrote that

Nothing is so firmly believed as whatever we know least about . . . For a Christian it suffices to believe that all things come from God, to accept them with an acknowledgement of His holy unsearchable wisdom and so to take them in good part, under whatever guise they are sent. . . . It is hard to bring matters divine down to human scale without their being trivialized.

Good to remember, every time we get worked up about who may or may not be part of our group, or get worked up about those who get worked up about such things. I’m reminded of a song I heard many years ago in church, a song with an annoying tune but an important text: “The kingdom of God is not meat and drink, but righteousness, peace, and joy.” Wilfred’s simple extension of acceptance to me so many years ago, on behalf of a group of monks more interested in hospitality than in doctrinal hair-splitting, still warms my heart. It could even serve as a model of God’s forgiveness. By the time we get around to telling the divine about our many faults, the response is always “I forgot what you said.” “Their sins and their iniquities I will remember no more.”