It is Memorial Day, a great day to honor those who have made sacrifices over the years, including the ultimate sacrifice of their lives, to protect our freedoms. It is also a good day to consider how well we are living out the freedoms that these sacrifices were made for.

Jeanne and I are anxiously awaiting the release of Season Five of House of Cards by Netflix tomorrow. On this Memorial Day I am thinking about politics; in one of the early second-season episodes, then Vice President Frank Underwood (played by the wonderful Kevin Spacey), fresh off another policy victory energized by skillful manipulation and lying, turns toward the camera for one of his patented asides to the insider audience. “I’m the second most powerful man in the country without a single vote being cast in my favor. Democracy is so overrated!” The events of the past several months make me wonder whether he might be right.

Jeanne and I are anxiously awaiting the release of Season Five of House of Cards by Netflix tomorrow. On this Memorial Day I am thinking about politics; in one of the early second-season episodes, then Vice President Frank Underwood (played by the wonderful Kevin Spacey), fresh off another policy victory energized by skillful manipulation and lying, turns toward the camera for one of his patented asides to the insider audience. “I’m the second most powerful man in the country without a single vote being cast in my favor. Democracy is so overrated!” The events of the past several months make me wonder whether he might be right.

Frank knows, of course, that technically the United States is not a democracy—it is far too big for that. It is a representative republic, in which eligible voting citizens elect representatives who then cast votes on behalf of those who elected them in legislative bodies from the local to national level. But this doesn’t dilute Frank’s intended point, which is that what matters in politics is power, manipulation, who you know, and money. This is true in any sort of government, since all forms of government are run by human beings, creatures motivated by self-interest and greed more than anything else.

Frank knows, of course, that technically the United States is not a democracy—it is far too big for that. It is a representative republic, in which eligible voting citizens elect representatives who then cast votes on behalf of those who elected them in legislative bodies from the local to national level. But this doesn’t dilute Frank’s intended point, which is that what matters in politics is power, manipulation, who you know, and money. This is true in any sort of government, since all forms of government are run by human beings, creatures motivated by self-interest and greed more than anything else.

Frank’s point puts him in good company. Plato’s Republic and Aristotle’s Politics are respectively two of the greatest works of political philosophy in the Western tradition, and even though both Plato and Aristotle were thoroughly familiar with the Athenian experiments in democracy that we look back on favorably, each were highly critical of this form of government. When Plato lists various forms of government from worst to best in the Republic, he ranks democracy as next to worst, only slightly better than tyranny.

Frank’s point puts him in good company. Plato’s Republic and Aristotle’s Politics are respectively two of the greatest works of political philosophy in the Western tradition, and even though both Plato and Aristotle were thoroughly familiar with the Athenian experiments in democracy that we look back on favorably, each were highly critical of this form of government. When Plato lists various forms of government from worst to best in the Republic, he ranks democracy as next to worst, only slightly better than tyranny.

There are many reasons for these great philosophers’ rejection of our favorite form of government, some of which were undoubtedly personal. Plato’s mentor Socrates was convicted and condemned to death by a jury of 501 of his Athenian peers in a straightforwardly democratic fashion—and Plato never forgave either Athens or its ludicrously misguided form of government. A generation later, when Aristotle found himself on the wrong side of the political landscape in Athens, he left town immediately, reportedly commenting “I do not intend to let Athens sin against philosophy twice.”

There are many reasons for these great philosophers’ rejection of our favorite form of government, some of which were undoubtedly personal. Plato’s mentor Socrates was convicted and condemned to death by a jury of 501 of his Athenian peers in a straightforwardly democratic fashion—and Plato never forgave either Athens or its ludicrously misguided form of government. A generation later, when Aristotle found himself on the wrong side of the political landscape in Athens, he left town immediately, reportedly commenting “I do not intend to let Athens sin against philosophy twice.”  Aristotle ended up going north to Macedonia where he was hired as tutor to a young man who would soon become one of the greatest tyrants the world has even seen—Alexander the Great.

Aristotle ended up going north to Macedonia where he was hired as tutor to a young man who would soon become one of the greatest tyrants the world has even seen—Alexander the Great.

Although their philosophical problems with democracy were many, Plato and Aristotle agreed that democracy’s deepest flaw is that it is built on a serious misreading of human nature. Democracy’s unique calling card is its openness to treating all eligible citizens as if they are all equally qualified to participate in making political decisions, an openness that is rooted in the bizarre assumption that these citizens are fundamentally the same in some important and relevant way that qualifies them for participation. This notion of fundamental human equality is so misguided that it would be laughable, say Plato and Aristotle, were it not that the effects of taking this notion seriously are so problematic.

Does it really make sense to invite the butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker to choose political leaders along with those far better suited by education, class, and abilities to do so? No more than it would make sense to invite a senator into the bakery or butcher shop to bake pastries or cut up a side of beef. There is an obvious hierarchy of skills and abilities, both physical and mental, among human beings and it makes obvious sense that a working society should identify these strengths and weaknesses efficiently so that each person can do what she or he is best suited for. This is why Plato ranks aristocracy—the rule of the aristos or the “best”—as the best form of government. Democracy is built on the idea that since all human beings are fundamentally the same, each of us can legitimately consider ourselves equally qualified for everything, including choosing our leaders. To which Plato and Aristotle say “Bull

Does it really make sense to invite the butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker to choose political leaders along with those far better suited by education, class, and abilities to do so? No more than it would make sense to invite a senator into the bakery or butcher shop to bake pastries or cut up a side of beef. There is an obvious hierarchy of skills and abilities, both physical and mental, among human beings and it makes obvious sense that a working society should identify these strengths and weaknesses efficiently so that each person can do what she or he is best suited for. This is why Plato ranks aristocracy—the rule of the aristos or the “best”—as the best form of government. Democracy is built on the idea that since all human beings are fundamentally the same, each of us can legitimately consider ourselves equally qualified for everything, including choosing our leaders. To which Plato and Aristotle say “Bull shit.”

shit.”

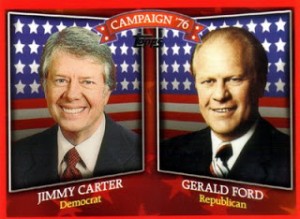

I remember facing these issues clearly in November 1976 as I walked into a polling booth in Santa Fe, New Mexico to cast my vote in my first Presidential election—Carter vs. Ford. As many first-time voters, I was dedicated to being the most informed voter in the country that election cycle. And it was a tough choice, much more difficult than any of the ten Presidential elections in which I have voted since. I had decided, after much thought, to vote for Carter a few days before the election and did so with pride on the first Tuesday of November.  The polling place was the elementary school just a couple of blocks down the street from the house we were renting; as I walked home after voting, I started having disturbing thoughts. What if some fool who had not spent one second thinking about or studying up on the issues followed me into the voting booth and voted for Ford rather than Carter because he liked elephants more than donkeys? What if my uncle,

The polling place was the elementary school just a couple of blocks down the street from the house we were renting; as I walked home after voting, I started having disturbing thoughts. What if some fool who had not spent one second thinking about or studying up on the issues followed me into the voting booth and voted for Ford rather than Carter because he liked elephants more than donkeys? What if my uncle,  who always votes straight Republican because he thinks Jesus was a Republican, has already cancelled my vote out? This sucks! Why should some uninformed boob’s vote count as much as my vote wrapped in intelligence and insight counts? Whose stupid idea was this “one person, one vote” thing? Exactly what Plato and Aristotle want to know.

who always votes straight Republican because he thinks Jesus was a Republican, has already cancelled my vote out? This sucks! Why should some uninformed boob’s vote count as much as my vote wrapped in intelligence and insight counts? Whose stupid idea was this “one person, one vote” thing? Exactly what Plato and Aristotle want to know.

Over the succeeding years I have had many opportunities to tell this story to a classroom of students and to share my proposed solution. Voting should be considered as an earned privilege for eligible persons, not as a right. Citizens of an eligible age, if they choose to vote, should be required to pass an eligibility quiz at the polling place—say a 70% on questions based on current issues and events as well as testing for basic knowledge of how government works—before entering the booth. I often tell my students that a liberally educated person has to earn the right to have an opinion. This would simply be a real application of that truth. I’m not saying that the quiz should be as demanding as what immigrants are required to pass for citizenship—how many natural-born citizens could pass that?—but something between that much knowledge and total ignorance is not too much to ask for.

Do You Have What It Takes to Pass the U.S. Citizenship Test?

My students, by the way, almost always think by a slight margin that this is a good idea. Those who don’t often raise questions like “who is going to construct the quiz?’ to which I reply “I will.”

The only reason to favor democracy in its various forms over other forms of government is the equality thing. If, notwithstanding Aristotle, Plato and the vast majority of political minds historically over the centuries, we truly believe that all persons share a fundamental equality so deep and definitive that it trumps the whole host of differences staring us straight in the face, then democracy is an experiment that deserves our continuing, energetic commitment and support.  But simply saying that everyone gets to vote regardless of race, gender, social status, wealth, or other difference-making qualities is not a sufficient expression of our belief in fundamental equality. Not even close.

But simply saying that everyone gets to vote regardless of race, gender, social status, wealth, or other difference-making qualities is not a sufficient expression of our belief in fundamental equality. Not even close.

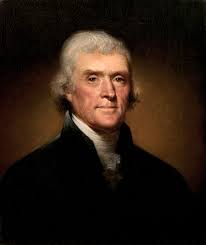

If we truly believe, in Thomas Jefferson’s memorable words, that “all persons are created equal and are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights,” we dishonor that belief by thinking that everyone getting to vote covers the bases. If we truly believe that all persons possess equal dignity as human beings, we cannot be satisfied with social and political arrangements that deny equal access for vast numbers of our fellow citizens to the various structures intended to facilitate the flourishing of that dignity throughout a human life. It is fine once or twice per year on Memorial Day or Independence Day to celebrate our continuing American experiment in democracy with flag waving and parades, but real patriotism requires spending the other days of the year on the hard work of actually trying to make this experiment work.