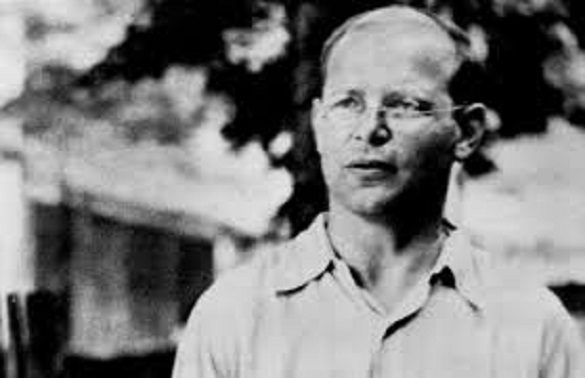

What is bothering me incessantly is the question of what Christianity really is, or indeed who Christ really is, for us today. The time when people could be told everything by means of words, whether theological or pious, is over, and so is the time of inwardness and conscience—and that means the time of religion in general. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Letters from Prison

One day a few springs ago, I spent a day as an outside reviewer for the Liberal Arts Program at a Connecticut state university an hour or so west of Providence. I shared these duties with an assessment-guru administrator from a state university in Massachusetts; we are tasked with jointly producing a report of five or so pages within three weeks. I offered to get the report started by writing a rough draft over the weekend, since I would have a long weekend away from classes from Thursday through Monday. “Why do you have a long weekend?” my envious colleague wanted to know. Ahh, the joys of working on a Catholic college campus—I often forget that not everyone gets Easter Break.

Although I grew up in a world in which Easter was the biggest event of the year, I have never settled into a tradition concerning how to celebrate it. Church, of course, but a familiar space filled with people who only show up once a year is a bit odd. Everything seems forced and unnatural, as if everyone is thinking “we’re supposed to be doing something special for Jesus’ resurrection, but we aren’t sure what it is. So we’ll just do what we usually do, only bit longer and louder.” A few Easters ago, after going to the 8:00 service , Jeanne and I celebrated by eating at “Not Your Average Joe’s” (their lettuce wraps and draft beers are outstanding) and went to see “Cinderella” (with Rose from “Downton Abbey” in the title role). Jeanne’s and my spiritual odysseys started at different poles and have evolved in different, perhaps opposite directions over time.

Jeanne was raised Catholic and resonates with many aspects of evangelical and charismatic Christianity, while I was raised evangelical, fundamentalist Baptist and find the vibrations of liturgical worship very attractive. It’s a good thing that our paths have a wide point of intersection, expressed very clearly by the passage at the beginning of this post written by Bonhoeffer in prison mere weeks before his execution by the Nazis. Who is Christ for us today? In less religious terms, what direct impact should our faith commitment have on how we live our lives together and individually?

Two of my courses have recently raised such questions in interesting ways. In “Grace, Truth and Freedom in the Nazi Era,” we studied the story of Le Chambon, an insignificant Protestant village in southeastern France that protected and saved thousands of Jewish refugees during the Nazi occupation in World War II. The spiritual leader and soul of the village, Andre Trocme, taught and exemplified an eminently practical and effective reading of the Gospels—they mean what they say. When asked about his motivations after the war, Trocme said

If Jesus really walked upon this earth, why do we keep treating him as if he were a disembodied, impossibly idealistic ethical theory? If he was a real man, then the Sermon on the Mount was made for people on this earth; and if he existed, God has shown us in flesh and blood what goodness is for flesh-and-blood people.

Around the same time, my “Markets and Morals” colloquium unexpectedly raised the question “How does a person of faith bring her or his values into a market that frequently runs contrary to such values?” Our text was Is the Market Moral?—a series of essays and responses by Rebecca Blank and William McGurn, two highly respected economists who are very serious about their Christian faith but disagree sharply about how it should intersect with a secular market economy. At one point McGurn distinguishes between Christian faith as a guide for an individual life and as a model for social reform, a separation that contemporary Christians frequently make.

A frequent mistake in the social arena is to apply personal virtues to social contexts. To put it another way, our social virtues may complement our personal virtues, but they are not the same. Not least of the weaknesses in so-called “Christian” prescriptions for economic life is the idea that the gospels are somehow a policy platform, as though the Golden Rule can be simply legislated.

I brought these two very different spins on how one’s religious values might apply to one’s practical daily life to my two seminars for small group discussion. One seminar thought that McGurn’s dividing “personal” from “social” virtues is essentially a cop-out, a road map for excusing oneself from seeking to bring needed change into the market and other social arenas. The other seminar focused their negative energies on Trocme’s Sermon on the Mount commentary, labeling it as “naïve” and “unrealistic.” I suspect that the range of true possibilities lies somewhere between Trocme and McGurn.

So what’s a person of faith to do? The news cycle regularly provides glaring examples of what happens when presumably well-intentioned legislators are unable to tell the difference between protecting religious freedom against perceived threats from the government and opening the door to discrimination in the name of religious values. And about those values—it’s not as if professed Christians have much agreement about what they even are. A notable case in Indiana a couple of years ago is a good illustration: The Christian faith that the owners of a pizzeria cited as the basis of their refusing to cater a same-sex wedding is the very Christian faith that many have relied on as they call attention to the resulting discrimination and less-than-Christ-like virtues being exhibited by the pizzeria owners and the advocates of the bill. Never has the separation of church and state looked so attractive from the perspective of both state and church.

Still, Rebecca Blank points out in Is the Market Moral? that a sharp separation between private and public is not an option for “Christians who believe that human beings cannot be whole without their most important institutions tethered in some acknowledgement to transcendent truth.” If my Christian faith is to be something more than a very interesting and complicated private hobby, a sharp separation of secular and sacred cannot be the order of the day. At the very least, Jesus’ annual emergence from the tomb back into the real world should remind the Christian that the Kingdom of Heaven is not a promise of a pleasant and problem-free afterlife, but is what the world, infused with the power of the Spirit and the energy of Christ-infused human beings, should be struggling toward now. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, waiting for his certain execution, captures it well.

Christians, unlike the devotees of the redemption myths, have no last line of escape available from earthly tasks and difficulties into the eternal . . . they must drink the earthly cup to the dregs, and only in their doing so is the crucified and risen Lord with them, and are they crucified and risen with Christ.