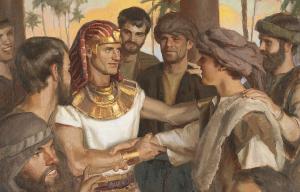

The reading from the Jewish scriptures for this coming Sunday is from Genesis 45 when Joseph, after several chapters of making his brothers’ lives miserable, reveals to them that he is indeed their lost brother whom they had sold into slavery when he was but a youngster. The story of Joseph, among other things, is a story of radical forgiveness. In my forthcoming book A Year of Faith and Philosophy, I consider the story of Joseph’s fraught relationship with his brothers and its implications when that story is paired during Ordinary Time with a familiar story from the gospels when Jesus tells Peter something unexpected about forgiveness.

The Proper 19 Year A readings from the Jewish Scriptures and Matthew’s gospel are stories about radical forgiveness. The last chapter of Genesis concludes the story of Joseph and his brothers; the brothers are afraid that after their father’s death Joseph will exact revenge for being sold into slavery many years earlier. In Matthew, Peter expects Jesus to provide a limit to how often he must forgive someone who has sinned against him. Both Joseph’s brothers and Peter find their expectations to be entirely wrong.

The Year A readings from the Jewish Scriptures have followed the Joseph saga for several weeks. Joseph is the eleventh and favorite son of Jacob, the first child of Jacob’s beloved wife Rachel. For any number of reasons, Joseph is intensely disliked by his older brothers—they first throw him into a well, then sell him to some traders who in turn sell him as a slave in Egypt to an important court official. Joseph’s brothers tell their father that his favorite has died.

Joseph’s story over the final chapters of Genesis tracks his path from slave to the most powerful man in Egypt other than the Pharoah, a rise fueled by luck, Joseph’s gift for dream interpretation, and his clearly being favored by God. When famine strikes years later and Jacob sends his sons to Egypt to purchase grain, they have no idea that the Egyptian official they have to negotiate with is none other than the brother whom they sold into slavery so long ago. He recognizes them, though, and clearly enjoys yanking their collective chain and making their lives miserable for a few chapters.

But ultimately “Joseph could no longer control himself,” and he reveals his true identity to his shocked and dismayed brothers. Joseph has every reason to use his power as a tool of vengeance and retribution against his brothers, but in an act of radical forgiveness he sends them home in order to bring Jacob and rest of the family to Egypt where the elderly Jacob will benefit from Joseph’s love and live out the rest of his days.

When Jacob finally dies, the older brothers are afraid that Joseph’s forgiveness was an act of respect for his father; now that Jacob is gone, Joseph might finally use his power to exact retribution. They offer themselves to him as slaves; in response he says, “Do not be afraid! Am I in the place of God? Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good.” In the coming decades the Israelites prosper in Egypt and multiply in numbers and strength until “a new king arose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph.”

One wonders if Joseph would have been as forgiving of his brothers if he had still been a slave when he encountered them years after they sold him into slavery. Forgiveness seems more possible from a lofty perch where he holds all the cards and they can no longer harm him. But the prayer that Jesus teaches his disciples makes it clear that unconditional forgiveness is a prerequisite for those who seek right relationship with God and to follow Jesus. Radical and unlimited forgiveness is to be offered to those who have wronged us, no matter who they are or what they have done.

When Peter asks Jesus about how far forgiveness is to extend in scope and frequency, he clearly has a specific issue in mind. He’s not asking about forgiveness in general, but in essence is asking, “How often do I need to forgive a person from our insider group who has wronged me?” In Season Four of The Chosen, Peter specifically has Matthew in mind as the one who has wronged him, a former tax collector who almost cost Peter his livelihood and his freedom before Jesus called him out of his tax-collecting booth with a simple “Follow me.” We can almost hear the attitude in Peter’s voice when he asks, “Seven times?”

Jesus’s answer—“seventy-seven times”—takes forgiveness out of the realm of the humanly possible and places it squarely in the realm of the miraculous. Only a thoroughly transformed person can offer unlimited forgiveness. But then, being transformed is what following Jesus is all about.

For reflection: We often say, “I’ll forgive, but I won’t forget,” as if forgiveness and forgetting that one has been wronged are two different things. But does the sort of forgiveness that Jesus is speaking about leave the door open for the wronged person to remember what the forgiven person did? Why or why not?