I’ve often said during my close to three decades of teaching philosophy on the college level that I did not enter academia because it’s one of the few places a philosopher can find to make a living. I entered academia because I wanted to be a college professor—philosophy just happened to be the disciplinary vehicle that got me there. If it hadn’t been philosophy, it would have been history (and if it hadn’t been history it would have been literature . . .).  Whatever it took to get me into the academic life. My approach to philosophy has always been contextual and historical; I have taken great delight in teaching regularly in an interdisciplinary course with a historian for over twenty years. As it turns out, my reading for the first ten days or so of Winter Break has reflected my love of history. Moving backwards from the first decade of the twentieth century to Ancient Rome, I have been reminded of just how relevant history is to understanding the present.

Whatever it took to get me into the academic life. My approach to philosophy has always been contextual and historical; I have taken great delight in teaching regularly in an interdisciplinary course with a historian for over twenty years. As it turns out, my reading for the first ten days or so of Winter Break has reflected my love of history. Moving backwards from the first decade of the twentieth century to Ancient Rome, I have been reminded of just how relevant history is to understanding the present.

Everyone knows a version of the truism that “those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it,” but few know where the original of the truism came from. As it turns out, lots of people have said something along these lines, from  Edmund Burke (“Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it”) and George Santayana (“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”) to

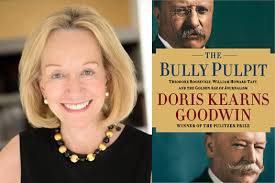

Edmund Burke (“Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it”) and George Santayana (“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”) to  Jesse Ventura (“Learn from history or you’re doomed to repeat it”) and Lemony Snickett (“Those unable to catalog the past are doomed to repeat it”). I finished the second half of Doris Kearns Goodwin’s The Bully Pulpit just before Christmas. Goodwin tells the story of the first decade of the twentieth century, focusing on Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, two of the towering political figures of the time. I am a great fan of Goodwin’s work and anxiously awaited reading The Bully Pulpit between semesters after her October lecture on campus as part of my college’s centennial celebration.

Jesse Ventura (“Learn from history or you’re doomed to repeat it”) and Lemony Snickett (“Those unable to catalog the past are doomed to repeat it”). I finished the second half of Doris Kearns Goodwin’s The Bully Pulpit just before Christmas. Goodwin tells the story of the first decade of the twentieth century, focusing on Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, two of the towering political figures of the time. I am a great fan of Goodwin’s work and anxiously awaited reading The Bully Pulpit between semesters after her October lecture on campus as part of my college’s centennial celebration.

The period of American history between the Civil War and the Great Depression has always been somewhat of an empty field for me, so I was fascinated to find that the politics of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had a remarkably contemporary feel.  A progressive movement (within the Republican party, no less) favoring the rights and interests of “the little man” is being resisted by big money, huge trusts and corporations run by fabulously wealthy individuals who are loath to release even a molecule of their power. The centers of activity are different from today—the progressive movement is centered in Kansas, Iowa, Minnesota, and the West with conservative resistance centered in the Northeast, but questions about how economics, politics, the common good, and foreign interests should be balanced were the same then as they are today. The Great Depression that followed within a decade after the end of the events in The Bully Pulpit shows that they did not figure things out very well back then—will we do better? The best I can say is that the jury is out on that one.

A progressive movement (within the Republican party, no less) favoring the rights and interests of “the little man” is being resisted by big money, huge trusts and corporations run by fabulously wealthy individuals who are loath to release even a molecule of their power. The centers of activity are different from today—the progressive movement is centered in Kansas, Iowa, Minnesota, and the West with conservative resistance centered in the Northeast, but questions about how economics, politics, the common good, and foreign interests should be balanced were the same then as they are today. The Great Depression that followed within a decade after the end of the events in The Bully Pulpit shows that they did not figure things out very well back then—will we do better? The best I can say is that the jury is out on that one.

My favorite takeaway from The Bully Pulpit is entirely personal. Threaded throughout the book are the stories of two remarkable marriages, Teddy and Edith Roosevelt, side by side with William and Nelly Taft.  The letters exchanged were intimate and revealing, including the following tribute from William to Nelly which I copied verbatim into Jeanne’s Christmas card:

The letters exchanged were intimate and revealing, including the following tribute from William to Nelly which I copied verbatim into Jeanne’s Christmas card:

I cannot tell you what a comfort it is to me to think of you as my wife and helpmeet. I measure every woman I meet with you and they are all found wanting. Your character, your independence, your straight mode of thinking, your quiet planning, your loyalty, your sympathy when I need it (as I do too readily), your affection and love (for I know I have it), all these make me happy just to think about them.

“Wow,” Jeanne said on Christmas morning, “you could have written that!” She also claimed, as did Nellie, that she didn’t deserve such a tribute—but Bill and I know better.

After The Bully Pulpit, it was on to SPQR (Senatus PopulusQue Romanus–“the Senate and people of Rome”), Mary Beard’s recent history of ancient Rome. One of my teaching partners this past semester in the interdisciplinary course in which I regularly teach is a classicist whose specialty is ancient Rome; when Fred gave the book an enthusiastic thumbs-up, I put it on my between-semesters reading list. I’m currently about half way through the book, and am reminded on almost every page to what extent the ancient Romans shaped our contemporary world. The issues they grappled with are still with us, issues almost too numerous to list. One in particular has caught my attention in SPQR, something about the Romans that I did not know until my colleague stressed it in a couple of lectures this past semester. Unique among ancient civilizations, the Romans were remarkably willing to incorporate outsiders into their world, not just as visitors, marginal members of society, or conquered people, but as citizens. The Romans were notably tolerant of different ways of doing things, an attitude that is, at least theoretically, something that we value in our country. Although the Romans were often suspicious and xenophobic in their initial actions toward others, the inhabitants of conquered territories were gradually given full Roman citizenship, along with the legal rights and protections that went with it. This openness, at least in theory, is something that we have aspired to during our country’s short history— which makes the current swing toward suspicion and concern about “the Other” in our politics and social attitudes so disturbing.

which makes the current swing toward suspicion and concern about “the Other” in our politics and social attitudes so disturbing.

There are reasons, of course, to be careful about openness—like Forrest Gump’s box of chocolates, one never knows what one might end up with. One interesting example from SPQR illustrates the point. Roman religion was complex, with a pantheon of gods and goddesses and a dizzying array of practices and festivals to honor them, events that also marked celebration of culture and what it meant to be Roman. But the Romans were also remarkably open to incorporating new deities and practices into their religion. In the early part of the second century BCE, the Great Mother goddess, the focus of worship in part of Roman territories in Asia Minor, was brought with great fanfare into Rome, at the advice of an ancient oracle, to be incorporated into the Roman pantheon. She was the patron deity of Troy, the mythical ancestral home of Rome, so in a sense the Great Mother belonged in Rome. Beard reports that the temple built to house her “ would be the first building in Rome, so far as we know, constructed using that most Roman of materials . . . concrete.” A deputation was sent to Asia Minor to collect the image of the goddess and transport her back—a deputation that included a highly placed senator and a Vestal Virgin. But, as Beard relates, “not everything was quite as it seemed.”

would be the first building in Rome, so far as we know, constructed using that most Roman of materials . . . concrete.” A deputation was sent to Asia Minor to collect the image of the goddess and transport her back—a deputation that included a highly placed senator and a Vestal Virgin. But, as Beard relates, “not everything was quite as it seemed.”

The image of the goddess was not what the Romans could possibly have been expecting. It was a large black meteorite, not a conventional statue in human form. And the meteorite came accompanied by a retinue of priests. These were self-castrated eunuchs, with long hair, tambourines and a passion for self-flagellation. This was all about as un-Roman as you could imagine. And forever after it raised uncomfortable questions about “the Roman” and “the foreign,” and where the boundary between them lay.

These are exactly the sorts of questions we must struggle with today. We might say that we will be accepting of the “Other” just as long as that Other over time becomes like we are. But what exactly are we? Romans regularly welcomed all sorts of people and practices into their sphere, and then had to grapple with the implications of openness. We must do the same, all the time remembering that were it not for a fundamental openness to strangers and the “Other” in our history, most of us would not be here.