Iris Murdoch was one of the philosophers whose work was front and center in my upper division course in contemporary philosophy a couple of semesters ago; last year was the centennial of her birth. She is a fascinating figure, an internationally respected philosopher who, at the height of her academic career, left academia to write novels full time. She ended up writing twenty-six of them, extraordinary investigations of the complexities and messiness of human relationships and commitments.

Murdoch claimed to be an atheist, but she also believed that true moral commitment required belief in something greater than ourselves, something transcendent not subject to the vagaries and whims of human existence. In the midst of her exploring these matters in her philosophical essays and her novels, she crafted several memorable definitions of basic concepts, including this definition of love:

Love is the perception of individuals. Love is the extremely difficult realization that something other than oneself is real. Love . . . is the discovery of reality.

Not long ago, I unexpectedly had the opportunity to engage with a striking story about the dynamic described in Murdoch’s definition in church.

Upon arriving at church for the early show, I found out that the lector scheduled to read that morning was ill. I’m a regular 8:00 lector, so I volunteered to read sight unseen, having no idea what the morning’s readings would be. The first passage was from the Book of Acts, an important and strange story that, in many ways, is the pivot point in the early Christian community’s understanding what it meant to be a follower of Jesus.

Acts, of course, is about the early Jesus communities and the spread of the “good news” inexorably from Palestine toward Rome and beyond. Often lost in the midst of the stories is just how disorienting and belief-challenging all of this must have been. Major debates raged about exactly what this new system of beliefs was. Was it a new version of Judaism? If so, then new Christians would be subject to the same dietary and behavioral rules from the Pentateuch that all Jews are subject to; male converts, for instance, should be circumcised.

Or was this new set of beliefs something new altogether, perhaps a challenge and direct threat to Judaism? Complicating the issue, at least according to evidence from the Gospels, is that Jesus himself was not always clear or consistent about who his message and teaching was for. Jesus was a Jew, and at times clearly said that his message was for the “House of Israel,” while at other times he packaged it for everyone, including non-Jews.

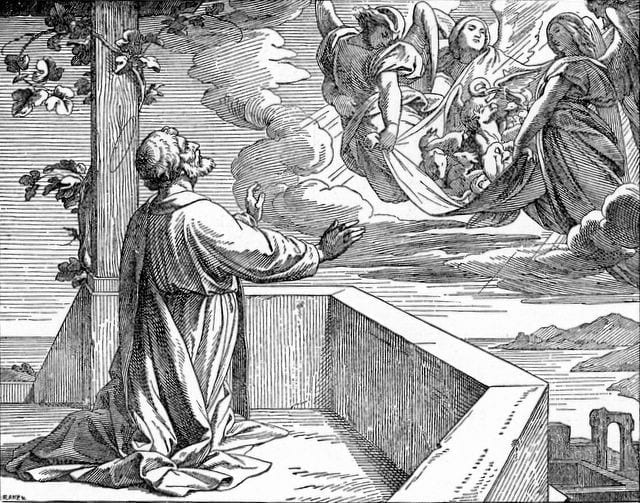

In Acts 10 we find Peter, the man who perhaps knew Jesus best and who, as the alpha disciple, is now at the forefront of spreading the good news, hungry and exhausted after an extended prayer session on the rooftop of a friend’s house in Joppa where he is staying. And then the strangest thing happens, as Peter reports to some critics in the next chapter, the story that I read that Sunday morning from the lectern:

In a trance I saw a vision. There was something like a large sheet coming down from heaven, being lowered by its four corners; and it came close to me. As I looked at it closely I saw four-footed animals, beasts of prey, reptiles, and birds of the air. I also heard a voice saying to me, “Get up, Peter; kill and eat.”

The sheet is full of all sorts of animals that, according to Jewish law, must not be eaten under any circumstances, as Peter immediately recognizes.

But I replied, “By no means, Lord; for nothing profane or unclean has ever entered my mouth.”

Peter knows the rules backwards and forwards; furthermore, he knows that for a Jew, strict obedience to these rules is required in order to be in right relationship both with God and with his community.

But as seems to happen so often in the context of what we think we know about God and our relationship with the divine, the rule book is thrown out entirely.

But a second time the voice answered from heaven, “What God has made clean, you must not call profane.”

Imagine Peter’s consternation and confusion. Imagine the consternation and confusion of his fellow Jewish believers when they find out that he has been hanging out with and spreading the good news to Gentiles. For after the voice from heaven in essence tells Peter “You know all of that stuff about what not to eat in order to be in right relationship with God, the stuff that has defined the diet of a faithful Jew for the past couple of millennia? Never mind. You can eat anything you want,” Peter is further informed that the human equivalent of unclean animals—the Gentiles—are now to be recipients of the good news that you might have mistakenly thought was just for Jews.

There’s this Roman centurion by the name of Cornelius who has been asking some really good questions—go to his house and help him out. Subsequent chapters in Acts pick up the theme. Cornelius and his household convert to the message of Christ, start speaking in tongues as Peter and the other disciples did at Pentecost, more conservative Jews are appalled, and eventually there is a big council in Jerusalem to decide what the hell’s going on. But Pandora’s box has been opened never to be closed again. The old rule book is out, and it’s anyone’s guess where this is going to end up.

Don’t you just hate it when someone changes the rules of the game at the very moment when you’ve gotten really good at working within the framework of the old rules? Just when you think you have everything relevant and necessary figured out, it all changes. For the past few years, we have been in the middle of such a time politically and socially in this country. Pundits and talking heads are regularly reduced to “I don’t know” and “beats me” when asked to predict what is likely to happen in the next several months. Public attitudes concerning homosexuality and same-sex marriage have evolved and shifted more quickly than anyone could have foreseen. Add in a life-changing pandemic, and disorientation is the new normal.

People are talking about the rights of transgendered people. More millennials are checking “none” when asked about their religious affiliation than check the box for an identifiable religion; these “nones” exhibit little interest and find no home in traditional religious structures. Sheets from heaven filled with female priests, less-than-conservative Popes, LGBTQ persons, Muslims, and every type of person that anyone could possibly be uncomfortable with are being lowered before the eyes of those who thought they knew what they were supposed to think about such things. What’s a person to do?

If Iris Murdoch’s definition of love is a good one, Peter’s vision was a challenge to see things differently, to view one’s reality with traditional and familiar lenses set to the side and to see with the eyes of love. If what tradition said was unclean is in fact clean, then everything is being reset. Persons of faith are, in our own confusing and disorienting time, being asked to see differently, to cast aside categories that are often entrenched, in order to see others as real human beings just as we are. We are called to see differently, so that the human being in front of us is not dark-skinned, poor, female, gay, disabled, conservative, wealthy, Muslim, male, straight, ugly, liberal, old, Christian, obese, or attractive, but rather is a person whose needs, hopes and dreams are real and independent of us. It is a task to come to see the world as it is.. When I believe that I have seen all there is to see, the Christ in me says “let me look again.”