A couple of weeks ago in the morning I was greeted in the driveway with Luther having a completely flat tire on the passenger front side (Luther is the name of our 2013 Ford Fusion—long story). We have the highest level of Triple A coverage, so I could have just called them and waited for some young punk to show up and put our donut spare tire on so I could drive to the local tire store (which has taken care of four cars worth of tire issues for us over the years) to get the flat repaired or replaced. But it was a nice day and I decided, to Jeanne’s confusion and consternation, to change the tire myself.

This was not entirely random—over the years I would guess that I’ve changed a flat tire at least three or four dozen times. But it’s been several years since the last flat tire event and Jeanne’s argument (well argued) was that she pays a shitload of money for AAA and this is exactly what she pays for. She was right. My guess at the time, though, was that it would be faster to change it myself than to wait for the AAA person to show up. My real argument, though, is that at age 69 I wanted to prove to myself and everyone who might notice that I could still do manly things and change a tire. So I did.

At the tire establishment I told this story quickly to the guy behind the counter. He responded with the affirming observation that “being able to change a tire is an important skill that most people under 40 years old don’t have.” I returned a couple of hours later to pick up the new tire (the old one was unrepairable but was fortunately under warranty)—behind-the-counter-guy said that if I waited for a half hour they could “throw the new tire on the car.” “No,” I responded, “I’ve got this.” I returned home, put on the new tire, and have felt proud of myself ever since.

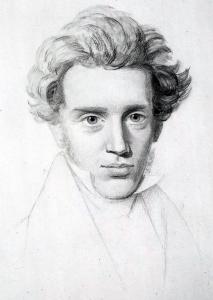

We live in a world in which we are bombarded with advertisements for products and services that will make our lives easier. In Irrational Man, William Barrett tells the following story about Kierkegaard as a young man:

He suddenly reflected that he had as yet made no career for himself whereas everywhere around him he saw the men of his age becoming celebrated, establishing themselves as renowned benefactors of mankind, whether materially by constructing railroads . . . or intellectually by publishing easy compendiums to universal knowledge, or—most audacious of all—spiritually by showing you thought itself could make spiritual existence systematically easier and easier . . . It occurred to him that since everyone was engaged everywhere in making things easy, perhaps someone might be needed to make things hard again; that life might become so easy that people would want the difficult back again; and that this might be a career and destiny for him.

Kierkegaard was undoubtedly an odd guy, but he’s one of my favorite philosophers—one who I very seldom get to use in class. His decision to bring “the difficult back again” to people as a career and destiny actually was a wise one. Because despite our continuous human attempts to make life easier, life is hard. Life is difficult. And we need to deal with it.

One of the reasons I resonate with Kierkegaard’s philosophy is that his faith commitments infused everything he wrote. Over the years, beginning with my early childhood, I’ve been exposed to versions of Christianity that either implied or expressly claimed that following Jesus was the best pathway to success and prosperity—usually implied or claimed by people who were anything but successful or prosperous. But rather than argue with advocates of the prosperity gospel—others have done that far more eloquently and effectively than I could (try Kate Bowler, for instance)—let’s cut to the chase. Jesus never said this. The gospels do not promise this.

Sure, Jesus says comforting things on occasion like “my yoke is easy and my burden is light,” but notice that there is still a yoke and a burden. Sure, Jesus says not to worry about tomorrow, but not because tomorrow won’t contain worrisome things. Rather we should not worry about tomorrow because “each day has enough trouble of its own.” There’s enough to worry about today, in other words. This following Jesus stuff is hard—and it should be.

In a number of his works, Kierkegaard makes a distinction between “Christendom” and “Christianity.” Christendom, on the one hand, is an institution, a top-down hierarchy, the various rules, prescribed actions, and rituals that human beings have constructed to limit and control human behavior and various dangerous elements of Christ’s message. This is what Simone Weil called “the Great Beast,” the powerful collective which attempts to control human freedom and choice in the name of God. For better or for worse, I was born into one specific, very powerful version of Christendom. Christianity for Kierkegaard, on the other hand, is a radical, individual commitment to following Christ at all costs, a commitment to the law of freedom and love so challenging and frightening that it shows Christendom to be a timid and safe mockery of faith.

The life of faith cannot be reduced to easy-to-perform activities that lead to guaranteed happiness and success. There is no AAA establishment to make following Jesus easy, even though many treat church and religion as precisely that sort of establishment. When difficulties come, when an unexpected faith version of a flat tire greets you unexpectedly, Paul says that you should “work out your own salvation with fear and trembling.” That sounds challenging. There’s a reason why Kierkegaard titled his best known book Fear and Trembling.