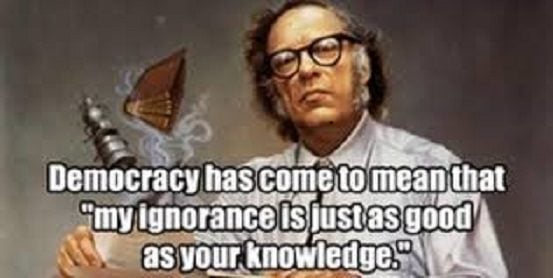

In early 1980, Isaac Asimov wrote something in a Newsweek article that has been making the rounds on social media over the past few months, something that could have been written yesterday.

The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that “my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.”

Asimov died over twenty-five years ago; I suspect that he would have adapted well to the internet and social media, and would be a powerful voice pushing back against the virulent anti-intellectualism that currently plagues us.

Asimov would have been interested in a recent book by Tom Nichols, who teaches at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. The thesis of The Death of Expertise: The Campaign against Established Knowledge and Why It Matters describes a classic “good news/bad news” situation. The good news: People are now exposed to more information than ever before, provided both by technology and by increasing access to every level of education. The bad news: These societal gains have helped fuel a surge in narcissistic and misguided intellectual egalitarianism that has crippled informed debates on any number of issues. Nichols writes that

The abysmal literacy, both political and general, of the American public . . . is the soil in which many other dysfunctions have taken root and prospered, with the 2016 election only its most recent expression . . . Americans have increasingly unrealistic expectations of what their political and economic system can provide. This sense of entitlement is one reason they are continually angry at “experts” and especially at “elitists,” a word that in modern American usage can mean almost anyone with any education who refuses to coddle the public’s mistaken beliefs . . . All voices, even the most ridiculous, demand to be taken with equal seriousness, and any claim to the contrary is dismissed as undemocratic elitism.

My twenty-five-plus years of college professorship convinces me that Nichols’ thesis is correct. I am solidly in the camp of “experts” and “elites” whose ideas and insights are more and more frequently dismissed out of hand for the reasons Nichols cites. I never thought that I would find myself living in a world in which the value of a person’s ideas would stand in inverse proportion to that person’s education and training, but that’s the world we increasingly find ourselves in.

My latest experience with this phenomenon was on Twitter a couple of days ago. I was in the beginning stages of what struck me as a reasonably civil Twitter-bate (new word) with a stranger who was, let’s say, slightly more conservative than I am. I had asked him to explain why, as he had expressed in a tweet, he thought Roy Moore would be the best thing that ever happened to the U. S. Senate; he apparently checked my Twitter home page and found out that I’m a college professor. Within a few minutes I received the following tweets in rapid fire, close enough together that I had no chance to even respond. I just sat back and watched the barrage roll onto my computer screen (I’ve cleaned up the spelling and capitalization—just can’t help myself):

- You’re a so called “Christian Philosopher” who touts Marxist propaganda? Gee, history proves how well that works out.

- As a professor, you’re either painfully confused, poorly educated or a straight up Marxist propagandist.

- Says the leftist clown, who claims he’s a Christian while supporting the very leftist policies that destroy religion and inalienable rights.

- Priceless: an Obama worshipping, Hillary supporting, America Hating Marxist Clown! Your page says it all

- What I find most troubling is how you claim to be a Christian, while you reject the human condition—that is, centuries of human history.

- Why would a Hegelian, Rousseauian, Marxist of your ilk care? Be proud of your beliefs—defend them!

Eventually I was able to squeeze in my own tweet, asking him what of Marx, Hegel and Rousseau he had read (also letting him know that “Rousseauian” isn’t a real word); he replied

- I enjoy philosophy and have read quite a bit, ergo, discerning your mindset wasn’t brain surgery.

After replying that I was impressed by how much he learned with confidence about me from a few tweets, I finished with this:

- Confidence is fine, but remember this from Montaigne: “On the loftiest throne in the world, you are still sitting on your own ass.”

Haven’t heard back from him since, but he may just be planning his next barrage. Of course, that’s what the “block” button is for.

What I really wanted to tweet was

- WHO DO YOU THINK YOU’RE TWEETING TO, YOU IGNORANT, SELF-IMPORTANT JACKASS?? MY TEN YEARS OF COLLEGE AND TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF TEACHING ON THE COLLEGE LEVEL TRUMP (PUN INTENDED) YOUR SELF-TAUGHT, PAINT-BY-NUMBERS ABSURDITIES!!

Followed by spiking my copy of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit to my office floor in triumph. But that’s too many characters for a tweet, and it wouldn’t be kind. But I must admit that I don’t feel particularly kind when someone claims that their ignorance masquerading as knowledge trumps what I consider to be my hard-earned real knowledge.

Millions of words have been and will be written about this “ignorance is just as good as knowledge” phenomenon, embraced by some and ignored or belittled on principle by others. I confess to annoyance when someone considers my years of education and twenty-five years of experience as a liability on issues that I actually know something about, but so be it. Let me instead say a word about the value of ignorance. Earned ignorance, that is. I often tell my students that a liberally educated person earns the right to have an opinion. Such a person also earns the right to embrace their ignorance—and that’s a good thing.

The godfather of Western philosophy, the patron saint of my academic discipline, is Socrates, a man whose only claim to fame—in his own estimation, at least—is that he did not know anything. He was a solid island of ignorance in a sea of Athenian pretensions to expertise and knowledge, and yet for millions over the centuries he has become the hallmark of wisdom. How does that work? How can wisdom coexist with ignorance? As it turns out, they go hand in hand—but it takes a lot of hard work and self-awareness to arrive at earned ignorance.

Michael Smithson, a psychologist teaching at the Australian National University, provides an interesting metaphor to illustrate the important dynamic between what we know and we don’t know. Imagine human knowledge as an island in a vast sea of ignorance. The island is dynamic and growing—living in the middle of it one might think it is a continent and be unaware of the surrounding sea. Smithson points out that the larger the island of knowledge grows, the longer the shoreline — where knowledge meets ignorance — extends.

This is why I find the teaching profession and facilitating the life of learning is so exhilarating and fascinating. The shoreline between sea and land is always fluctuating as the tide rolls in and rolls out. The line of demarcation between land and water, between knowledge and ignorance, is shifting sand—that’s the territory of true learning. The pedagogy of uncertainty and ignorance favors questions over answers, uncertainty over certainty, the unknown over the set and established.

The message here is to keep seeking the shoreline, rather than settling down permanently in the middle of the island and pretending that there is no ocean of ignorance surrounding what appears to be a fixed and vast continent. Socrates took great delight in leading his fellow Athenians, who were sure that “it doesn’t get any better than this” in terms of culture, sophistication, and knowledge, to the shoreline of knowledge in order to catch a glimpse of how much vaster our ignorance is than our knowledge.

This would be good for all of us to remember the next time we are tempted to present our favorite religious or political commitments, many of which were handed to us years ago and which we have never thought to question, as if they are insights into the mind of God. They aren’t—they are, instead, the natural starting point of what should be a life-long exploration of the shoreline between knowledge and ignorance. Happy exploring!