I spent two hours of seminar last Friday with twelve honors freshmen enjoying the wonders of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the source of many of my favorite stories as a child. I was so taken with ancient mythology that I read it in secret at times I was supposed to be reading the Bible. The seminar reminded me of one of my earliest posts on this blog a couple of years ago–how stories shape our lives.

Some of my favorite stories growing up come from Greek and Roman ![images[1]](http://wp.production.patheos.com/blogs/freelancechristianity/files/2012/09/images1.jpg) mythology. Edith Hamilton’s Mythology was one of my regular reading companions–sort of like a mid-twentieth century Ovid–so much so that my parents must have replaced a torn and worn out copy with a new one at least three times. What’s not to like? Action, violence, sex—they were better than comic books! The Olympian deities are gigantic projections of human beings, with all of our strengths and shortcomings, likes and dislikes, jealousies and kindnesses, massive egos and even more massive insecurities. Human beings in these stories, if they are smart, look (usually unsuccessfully) look for a place to hide when the deities start throwing their divine weight around, as the fallout frequently lands on unwitting and innocent mortals. Yet occasionally mortals are able to manipulate the blundering gods and goddesses by offering the right sacrifice, stroking the right part of a divine ego, making deals that the less-than-omniscient deities fail to recognize as guaranteed to end in results that will thwart their purposes. I think the main reason I took four years of Latin in high school was simply because it gave me to opportunity to be immersed deeply in the ancient myths

mythology. Edith Hamilton’s Mythology was one of my regular reading companions–sort of like a mid-twentieth century Ovid–so much so that my parents must have replaced a torn and worn out copy with a new one at least three times. What’s not to like? Action, violence, sex—they were better than comic books! The Olympian deities are gigantic projections of human beings, with all of our strengths and shortcomings, likes and dislikes, jealousies and kindnesses, massive egos and even more massive insecurities. Human beings in these stories, if they are smart, look (usually unsuccessfully) look for a place to hide when the deities start throwing their divine weight around, as the fallout frequently lands on unwitting and innocent mortals. Yet occasionally mortals are able to manipulate the blundering gods and goddesses by offering the right sacrifice, stroking the right part of a divine ego, making deals that the less-than-omniscient deities fail to recognize as guaranteed to end in results that will thwart their purposes. I think the main reason I took four years of Latin in high school was simply because it gave me to opportunity to be immersed deeply in the ancient myths![images[7]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2012/09/images71.jpg) . I spent fourth period senior year with Ms. Thomson and one other Latin geek translating large portions of Ovid’s Metamorphoses—nothing better.

. I spent fourth period senior year with Ms. Thomson and one other Latin geek translating large portions of Ovid’s Metamorphoses—nothing better.

My mother used to occasionally try to get me to put down Edith Hamilton and pick up my Bible. But I knew the Bible stories backwards and forwards from the hours and days spent in my home away from home, church—I’d even memorized a lot of the dialogue and plots of these stories (in King James English, of course). My mother worried that I wasn’t paying sufficient Baptist homage to the Bible stories as opposed to the pagan Greek stories. When she couldn’t pry me away from Edith, she would say “you know, of course, that these are only stories?” Opposed, that is, to the stories in the Bible, which are true, meaning that they are factual reports of things that really happened, not stories at all. As a good son, I paid lip service to the distinction that my mother, out of concern for her heretic-in-the-making son, was insisting upon.

But I never bought it. The stories in the Old Testament (by far the most interesting Bible stories to a young kid) were just too much like the Greek and Roman myths for me to make a sharp distinction. God in the Old Testament is just as arbitrary, whimsical, loving, nasty, powerful, and petty as the various Greek deities. He gets into arguments and debates with various mortals and sometimes loses. He sometimes gets into a snit and goes silent, while at other times you just wish He’d shut the hell up and leave people alone. If a skilled psychologist sought to identify all of the various, conflicting personalities of God in the Old Testament, I’m sure they would be at least as great in number as the residents of Olympus. The “truth” of the Bible stories for me did not depend on whether they “really happened”—they were true because they rang true in a deep place.

He gets into arguments and debates with various mortals and sometimes loses. He sometimes gets into a snit and goes silent, while at other times you just wish He’d shut the hell up and leave people alone. If a skilled psychologist sought to identify all of the various, conflicting personalities of God in the Old Testament, I’m sure they would be at least as great in number as the residents of Olympus. The “truth” of the Bible stories for me did not depend on whether they “really happened”—they were true because they rang true in a deep place.

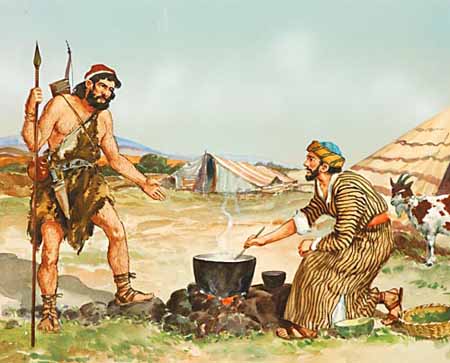

At a very young age, for instance, I resonated with Jacob in Genesis; he’s still my favorite character from the Bible. As the younger of two sons, I identified with Jacob’s preference for his mother and for hanging around the house rather than going out hunting and killing things, something my older brother did with my Dad. Jacob’s ability to regularly outsmart and manipulate his doofus older brother Esau rang true, because I was sure I could get my equally challenged doofus older brother to do whatever I wanted whenever I wanted . I was sure that if Baptist fathers gave special and exclusive blessings to oldest sons, I could get my older brother to hand over his blessing in exchange for a can of soup. Jacob is persistent and smart, but he’s also a conniver and occasionally has a very difficult time being truthful and transparent to himself and others. He loves his family, but some of them more than others. He’s courageous at times and a total chicken at others. He wants to know God, but wants to write the script according to which that knowledge will unfold. Every time the divine breaks through in a vision or dream, Jacob immediately wants to nail it down and contain it by naming it. In other words, looking back, my original attraction to Jacob makes a lot of sense, because he’s a lot like me.

. I was sure that if Baptist fathers gave special and exclusive blessings to oldest sons, I could get my older brother to hand over his blessing in exchange for a can of soup. Jacob is persistent and smart, but he’s also a conniver and occasionally has a very difficult time being truthful and transparent to himself and others. He loves his family, but some of them more than others. He’s courageous at times and a total chicken at others. He wants to know God, but wants to write the script according to which that knowledge will unfold. Every time the divine breaks through in a vision or dream, Jacob immediately wants to nail it down and contain it by naming it. In other words, looking back, my original attraction to Jacob makes a lot of sense, because he’s a lot like me.

A couple of years ago, when I read Kathleen Norris’ definition of “myth” in Amazing Grace as “a story that you know must be true the first time you hear it,” I was jerked up short. I knew this definition to be true the first time I read it. In ethics classes with nineteen to twenty-one-year-olds who are predominantly survivors of twelve years of parochial education, I lean heavily on Alasdair MacIntyre’s insight that we human beings are “story telling animals”—we understand ourselves and each other by telling stories.

A couple of years ago, when I read Kathleen Norris’ definition of “myth” in Amazing Grace as “a story that you know must be true the first time you hear it,” I was jerked up short. I knew this definition to be true the first time I read it. In ethics classes with nineteen to twenty-one-year-olds who are predominantly survivors of twelve years of parochial education, I lean heavily on Alasdair MacIntyre’s insight that we human beings are “story telling animals”—we understand ourselves and each other by telling stories. Through the stories we tell, we make sense of our past and do our best to recreate the world by telling better and better stories projected into the future. We are lived stories, in the middle of a “never-ending story” with themes and characters that we catch only brief glimpses of. At the outset of The Gates of the Forest, Elie Wiesel tells the story of a rabbi who confesses to a young listener that he’s old, his memory is failing him, and all he can do is tell stories. But, the rabbi concludes, “It is sufficient. For God made man because He loves stories.”

If my mother were here (and how often I wish she were), I’d try to convince her, with scholarly support from Plato through Nietzsche to Rorty, that my childhood conviction was right, that the stories from ancient mythology and from the Bible are true in the same, human affirming and life defining ways, mirrors of what we as human beings are and suggestions of what we can hope for and perhaps become. I’d end with “Q.E.D., Mom–What do you think of that?” And she’d reply, “That’s wonderful, honey, but the stories from the Bible are really true.”