My youngest son was a vet tech for a number of years and had many informed opinions about different types of animals. The stupidest animals he ever dealt with were sheep—I always knew that it is not a compliment when human beings are regularly likened to sheep in the Bible. For instance, Justin tells me that all one has to do to get a sheep to behave is to put it on its back. Once feet up, a sheep apparently believes that she or he has been conquered and will not struggle, no matter what is done to it. Just watch the movie “Babe” and you’ll find out how dumb sheep are.

“Babe” also lets us know which animal occupies the other end of the intelligence spectrum from sheep. Despite a lot of bad press of various sorts, pigs are incredibly intelligent; Justin says that the some of the pigs he dealt with were smarter than a lot of the humans he knows. Pigs get a bad rap—they have the reputation of being lazy, they are fat, they are dirty, and there is no situation in which being called a “pig” is a good thing. Pigs are animals-non-grata in the Bible—on the unclean and “don’t eat” list along with a number of other beasts. And pigs are major players in one of the strangest episodes to emerge from the stories of Jesus.

In Luke 8 Jesus and his entourage are in the land of the Gerasenes, in what would be modern-day Jordan. There he encounters a man “who had demons,” a man who has been living naked “among the tombs” for many years. The man (or the demons) knows Jesus on sight and begs for mercy. After a brief exchange, Jesus casts the demons out of the man and, agreeing to their request sends them into a herd of swine minding their own business close by. The pigs rush down a hill into a nearby lake and drown. The swineherds run to town reporting what just happened (and undoubtedly also to file a legal claim against Jesus for ruining their livelihood). Although somewhat unusual, on one level the story is just another tale of Jesus’ compassion and healing powers; hidden in the narrative, however, are at least a couple of details worth considering.

The man knows Jesus’ name, but Jesus does not know his, nor apparently does he know the identity of the entities possessing the man. Jesus asks “What is your name?” to which the man answers “‘Legion;’ for many demons had entered him.” Contemporary scholars often stress that ailments identified as possession by evil spirits in the ancient world were almost certainly diseases such as epilepsy, psychological disorders, or any medical problem manifesting itself in unusual behavior or appearance. But we need not delve into a discussion of whether Satan and demons are real in order to find value in Jesus’ question to the man.

In a Sunday sermon on this text not long ago, my good friend Marsue, who is an Episcopal priest, advised her congregation to “Name your demon.” “Have you ever felt that something just isn’t right, that something inside is out of whack but you don’t know what?” Marsue asked. As the saying tells us, your giant goes with you wherever you go. And so do your demons. Thoreau once wrote that most of us live lives of quiet desperation and go to the grave never grappling with the sources of that desperation.

This applies not only on an individual but on a collective level. It is much easier to project our fears and concerns onto the “Other,” whether defined by religious commitment, racial identity, countries of origin, or sexual orientation, than it is to realize that our fears and concerns always are rooted much more closely to home than we choose to accept.

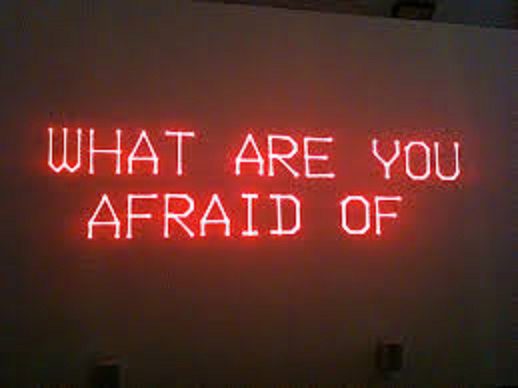

Iris Murdoch once suggested that one of the best questions one can ask oneself regularly is “What are you afraid of?” If our consistent answer is “those who are most unlike us,” it is time to consider the possibility that we are turning others into what we are most uncomfortable with and fear about ourselves. The first steps toward naming my demons begin with identifying those persons and situations I am most uncomfortable with and asking “what am I so afraid of? What is its name?” Just like vampires, our demons cannot survive when we shine light on them.

In the story from Luke, after Jesus casts the demons into the pigs, the news spreads quickly and the community comes to see the healed man “clothed and in his right mind.” Jesus is a rock star because he has made a man who everyone avoided like the plague whole again and the townspeople invite Jesus and the man into their town for a big celebration. Well . . . not so much. Instead, “all the people of the surrounding country of the Gerasenes asked Jesus to leave them; for they were seized with great fear.”

There’s that “f” word again—what were these people afraid of? Their disturbing reaction to the healing of a tormented and troubled neighbor raises another important question. Not only does each of us need to ask “what am I afraid of?” but each of us also needs to ask “do I want to be free of that fear?” For years, the residents of Gerasa were very clear about who this demon-possessed man was and how to handle him. “Stay away from him.” “Don’t let the kids go near the cemetery where he lurks unaccompanied.” “He’s dangerous.” “There’s no hope for him—best to ignore him as much as possible.” But now, all of a sudden, everything has changed.

Dealing with demons is a risky business. Risky because I might be so used to and comfortable with my demons that I cannot imagine life without them. As Jesus asked the man at the pool of Bethsaida, “do you want to be made whole?” Although we might deny it, the immediate answer for many of us is undoubtedly “I’m not so sure.” I can’t imagine myself without my prejudices, my preconceptions, my weaknesses—many of which I did not choose but which have defined me for longer than I can remember.

This is also risky for those around me, because now all of their preconceptions are brought to light as well. All of the categories that defined the previously demon-possessed man—someone to be avoided, a dangerous person, insane, and so on—now have to be rethought. More generally, they have discovered that the “Other” is exactly the same as they are.

Retooling our preconceptions and discovering what is common among us rather than what divides us is very difficult work, work that directly challenges our comfortable categorizations. Do we really want to know that those whom we regularly keep at arm’s length are, regardless of religious commitment, race, or sexual orientation exactly the same as we are in every respect that matters? The citizens of Gerasa knew that what had just happened to the demon-possessed man was a total game changer—and they were not ready or willing to play the new game.

We are not told how they responded to the newly healed man over time, but we do know that they asked the man responsible for the healing to leave. Naming our demons requires also taking responsibility for what comes afterward—a radical retooling and rethinking of everything we think, say, and do. That’s a lot of work—it’s a lot easier just to hang on to our demons. Unless we actually want to be made well.