Somewhere not long ago I heard or read that one of the top television programs in Finland (or Sweden or Norway) is a few hours of watching a fire burn in a fireplace. I don’t know whether or not this is true—I would hope that my Scandinavian cousins might go for a real fire in a fireplace rather than one on a screen. But Google “fireplace youtube video” and you will find several dozen to choose from.

During the two-hour final exam in one of my classes a couple of years ago, I put a fireplace video on the big screen up front while the students worked on their exams. Nobody commented on what I thought was a stroke of genius. I didn’t notice a significant increase in the quality of the exams, but I’d like to believe that it might have reduced the stress a bit. There is something mesmerizing and comforting about such videos; the one I chose is complete with the crackling of the logs (and no elevator music in the background). It’s low maintenance, too. No heat, but no kindling, no mess to clean up, no chance of the fire jumping out of the fireplace and causing damage, and no burns. There’s a lot to be said for domesticated fire—except that it isn’t fire. That’s what usually happens when we try to domesticate something wild and dangerous. It becomes something else entirely.

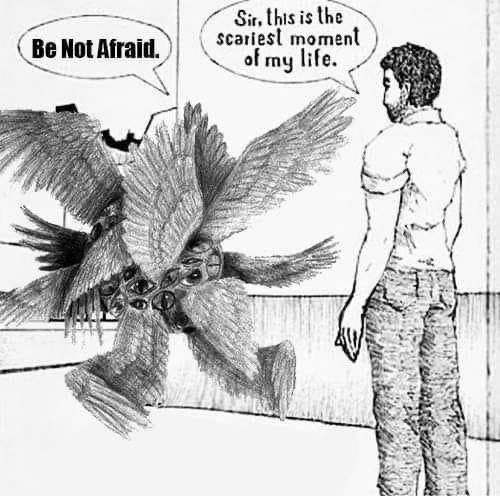

Last Sunday’s reading from the Jewish Scriptures is so familiar that we often don’t pay attention to just how disturbing and frightening the scene is.

I saw the Lord sitting on a throne, high and lofty; and the hem of his robe filled the temple. Seraphs were in attendance above him; each had six wings: with two they covered their faces, and with two they covered their feet, and with two they flew.

These were not the Renaissance neat-and-clean angels dressed in white or chubby Valentine’s Day cherubs. They looked something like this.

By the time Isaiah several verses later, after experiening directly divine shock and awe, answers in fear and trembling “Here I am, send me,” he knows that he’s probably in for a wild ride. And so he is, as is anyone with the nerve to answer the divine call in that way.

In his homily, my friend and our priest Father Mitch focused on the disturbing elements of the text. It is so easy to treat the Christian faith, or faith of any sort, as a light life, something requiring a few weekly commitments that aren’t a heavy lift. The Isaiah scenario, however, is what the author of Hebrews meant when writing that “it is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God.” In Holy the Firm, Annie Dillard asks

Why do we people in churches seem like cheerful, brainless tourists on a packaged tour of the Absolute? . . . On the whole, I do not find Christians, outside of the catacombs, sufficiently sensible of conditions. Does anyone have the foggiest idea what sort of power we so blithely invoke? Or, as I suspect, does no one believe a word of it? The churches are children playing on the floor with their chemistry sets, mixing up a batch of TNT to kill a Sunday morning. It is madness to wear ladies’ straw hats and velvet hats to church; we should all be wearing crash helmets. Ushers should issue life preservers and signal flares; they should lash us to our pews. For the sleeping god may wake someday and take offense, or the waking god may draw us out to where we can never return.

As Mitch noted on Sunday, those waiting to process down the aisle on a given Sunday morning speak to each other in hushed whispers in the back. Perhaps they are wondering whether they really want to get this show started. Who knows what might happen when we invite the transcendent to show up?

In When God is Silent, Barbara Brown Taylor suggests that we often opt for a domesticated God because we suspect that the alternative is too disturbing to consider. Religious history is littered with stories of those who asked to meet God face to face and barely survived to tell about it. “Many pray for an encounter with the living God,” Taylor writes. “Those whose prayers are answered rarely ask for the same thing twice.” Persons of faith complain (frequently, endlessly) that God is silent, that no direct communication from the divine is ever forthcoming, at least not in a language anyone can understand. Just ask Job. But it just might be that God is silent because this is what, in our heart of hearts, we have asked for.

Just as the Book of Exodus reports that the children of Israel quaked in their boots at Mount Sinai after God’s direct communication, we would rather dabble around the edges, and we would much rather hire someone to represent God to us (and us to God) than take the face to face risk.

We are not up to direct encounter with God. We want it but we don’t want it. We want to be warmed, not burned, except where God is concerned there is no such thing as a safe fire. Safe fire is our own invention. It is what we preach to people who, like us, would rather be bored than scared.

The next time I am in church I’ll have a hard time forgetting the YouTube video of a fireplace burning. A pleasant enough experience, I suppose, but offering nothing of the warmth and danger of the original. As we proceed through the various portions of the liturgy—Gloria, sermon, creed, confession, collection, Sanctus, Agnus Dei and so on—Annie Dillard will be poking me in the side.

I often think of set pieces of liturgy as certain words that people have successfully addressed to God without their getting killed . . . If God were to blast such a service to bits, the congregation would be, I believe, genuinely shocked.

Indeed, we would be—and attendance the following Sunday would be affected. Much better to pretend that we know what we are doing and that God somehow is entertained. Because the alternative—that God might actually show up and do something, including making us responsible for what we so blithely parrot every week—makes us uncomfortable. And above all else, human beings want to be comfortable.

The life of faith is not neither comfort, stability, nor security. And, as Annie Dillard describes in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, we should not want it any other way.

There is always an enormous temptation in all of life to diddle around making itsy-bitsy friends and meals and journeys for itsy-bitsy years on end. It is so self-conscious, so apparently moral, simply to step aside from the gaps where the creeks and winds pour down, saying, I never merited this grace, quite rightly, and then to sulk along the rest of your days on the edge of rage. I won’t have it. The world is wilder than that in all directions, more dangerous and bitter, more extravagant and bright. We are making hay when we should be making whoopee; we are raising tomatoes when we should be raising Cain, or Lazarus.