It hardly seems possible that I am now in the tenth calendar year of writing this blog (my first post was at the end of August 2012). It seems even less possible that it was fifteen years ago that I first began experimenting with writing short essays, the type of writing that eventually produced and continues to sustain this blog, as well as two books that have grown out of such essays. I applied to the 2007 Southampton Writers’ Conference at my wife Jeanne’s insistence. The extreme academic and the even more extreme introvert in me screamed “No!” but I applied anyways, fully expecting that I would be rejected.

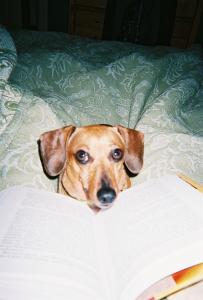

I wasn’t. My assigned workshop was “Literary Essay” (not my first choice—but I no longer remember what my first choice was); each of the fifteen workshop participants wrote daily 500-word essays, which were submitted to colleagues for critique and (hopefully) helpful evaluation. My essays tended to praise the virtues of my dog  and the Boston Red Sox, while frequently expressing struggles with faith, God, religion, and my own very human inadequacies. About halfway through the two-week conference, during a critique session when I and my most recent submission were on the hot seat, one of my colleagues said “You write so negatively about yourself in your essays. You seem like a really nice guy—why do you have such a negative self-image?” Other colleagues murmured their agreement.

and the Boston Red Sox, while frequently expressing struggles with faith, God, religion, and my own very human inadequacies. About halfway through the two-week conference, during a critique session when I and my most recent submission were on the hot seat, one of my colleagues said “You write so negatively about yourself in your essays. You seem like a really nice guy—why do you have such a negative self-image?” Other colleagues murmured their agreement.

My immediate reaction was not defensive—despite being supremely (perhaps over-) confident in some aspects of my life, my overall self-image at that point in my life was more negative than positive. My internal reaction instead was a quick realization that I might be the only person in the room who didn’t think he or she was pretty much okay.

My fourteen colleagues were a diverse bunch, including a specialist in Chinese history, an archaeologist, a high school student whose mother was running the conference, a vice president of an international banking firm, a local politician, a poet who just published her first collection of poems, several self-described “writers conference rats” (one was at this conference for the seventh straight year), and our workshop leader, a well-known essayist and columnist who had just published his third novel. And they were mildly uncomfortable with my being explicit about my self-doubts and honest about my shortcomings and failures.

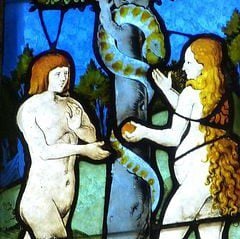

I was in the midst of some difficult internal stuff that summer, but I’ll bet many of my colleagues were too. I soon realized that what really made me different from them is original sin—it has defined me for as long as I can remember, and they had never heard of it. I learned at a very early age that I don’t measure up, that I’m not good enough, that “within me dwells no good thing.” And it’s not an exclusively Christian idea (although it sometimes feels as if it is); the Psalmist says, “I was brought forth in iniquity, and in sin my mother conceived me.” We’re all screwed from the start. Thanks Adam and Eve—I’ll be posting an essay about different angles on that iconic couple soon.

Some make a bigger deal of this than others. Martin Luther, the guy responsible for Protestants, likened divine grace to a layer of freshly fallen snow covering a pile of shit. Grace doesn’t transform the pile—shit is still shit—but it covers it so that its smell is not quite as offensive and it doesn’t look quite as disgusting. And guess who the offensive pile is . . . me. You are as well, so don’t feel too sorry for me.

This is a wonderful foundation upon which to build a positive self-image, but it’s the engine that drives a lot of religious activity. I remember that several years ago the Catholic Dominican Matthew Fox was excommunicated for teaching, among other things, that the doctrine of original sin is wrong and for writing books with titles like Original Blessing. He became an Episcopal priest after his excommunication, which makes sense—we Episcopalians will take anyone as long as they appreciate good liturgy and have sufficiently liberal social and political commitments.

To be honest, after more than thirty years as a recovering Protestant involved in Catholic higher education, I’ve discovered that most Catholics I know take original sin far less seriously than the people I grew up with did. Catholics pay lip service to the notion that human beings need divine help; my people meant it. They told me I deserved to go to hell and would undoubtedly end up there unless I was “right with Jesus.” And my workshop colleagues wondered why I wrote negatively about myself.

Many groups of people, both religious and otherwise, speak as if they have a corner on feeling guilty and inadequate. I knew no Catholics when I was growing up, but now that I spend a large portion of my time with them professionally and have many Catholic friends, I know all about Catholic guilt, despite the fact that they don’t talk about original sin that much. I was surprised to find out that Catholics think that Catholic guilt is particularly debilitating, just as they were surprised to find out that I know all about it; I just call it Protestant guilt. I’ve even participated in good-natured debates about whose guilt is more paralyzing.

Everyone knows about Jewish guilt, Irish guilt, and so on. We apparently don’t need religious doctrine to tell us that we are inadequate and flawed. We just need to be human beings. John Henry Newman wrote that just observing what’s going on around us with the slightest care reveals that humanity is afflicted by “some aboriginal calamity.” That’s a wonderfully British, urbane, nineteenth century way of saying “we’re really f–ked up.”

It’s true. There’s something fundamentally askew at our core, and we all know it. Many manage to cope with this by ignoring it, by refusing to include it in their vocabulary, by defining themselves in terms according to which they can be acceptable and successful. “I’m okay, you’re okay”—but as Emily Dickinson suggests, there’s still a “tooth that nibbles at the soul”—we’re not okay.

A decade ago, toward the end of a lovely lunch conversation, a new friend and colleague observed that “it’s hard being a person,” in the same matter-of-fact tone of voice in which he might have said “these waffles are cold.” I said in response that what told me, years ago, that Simone Weil is my kind of woman was when I read in her notebooks that, in her estimation, “human life is impossible.” So, that’s where I begin. I’m not okay and I need help. And the first step forward has to be one of trust, of a hope that this can be better. Iris Murdoch writes that “God is a belief that at our deepest level we are known and loved, even to there the rays can penetrate.” Let it be so.