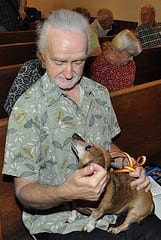

I was reminded yesterday that exactly eight years ago, one of my favorite pictures of my beloved dachshund, Frieda, was taken. I was the lector for “Blessing of the Animals” Sunday, celebrated at our Episcopal church the first Sunday in October in conjunction with Saint Francis day. Jeanne and I brought our three dogs (two dachshunds and a Boston terrier) to be blessed by our rector and good friend Marsue; I carried Frieda with me to the lectern as I read the story of Balaam and his ass from Numbers. Frieda stared the parishioners down as I read.

I was reminded yesterday that exactly eight years ago, one of my favorite pictures of my beloved dachshund, Frieda, was taken. I was the lector for “Blessing of the Animals” Sunday, celebrated at our Episcopal church the first Sunday in October in conjunction with Saint Francis day. Jeanne and I brought our three dogs (two dachshunds and a Boston terrier) to be blessed by our rector and good friend Marsue; I carried Frieda with me to the lectern as I read the story of Balaam and his ass from Numbers. Frieda stared the parishioners down as I read.

It was bittersweet, to say the least, to unexpectedly see the picture from eight years ago pop up on my Facebook feed. Frieda died thirteen months ago, and although I don’t get tears in my eyes any more every time I see her picture (which is a good thing, since her pictures are everywhere in our house), I’m quite sure I’m never going to fully get over her being gone. Tomorrow is “Blessing of the Animals” Sunday, and I am remembering what a blessing Frieda was over the twelve years she graced us with her Type-A presence.

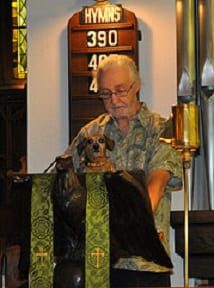

Two years after the picture of Frieda and me at the lectern was taken, Marsue asked me if I would like to give the sermon for Saint Francis Sunday. Knowing that, for Marsue, “Blessing of the Animals” was a bigger liturgical event than Easter or Christmas, I was honored to be asked. Here’s what I said from the pulpit that morning:

On weekday mornings I try to start the day by reading the Psalms appointed for the morning in the daily lectionary. A couple of days ago on Friday morning as I squinted through bleary, sleep-filled eyes, I was greeted by Psalm 19, my favorite Psalm ever:

The heavens declare the glory of God

And the firmament showeth His handiwork

Day unto day uttereth speech

And night unto night showeth knowledge

There is no speech or language; their voice is not heard

But their sound is gone out into all lands

And their words unto the ends of the world.

Or so I learned it as a child in the King James Version. Psalm 19 is a celebration of God’s creation, a reminder that we can encounter God’s glory and goodness simply by looking up attentively. This morning’s Psalm is a similar reminder that the divine is imprinted in creation. Psalm 104 is a beautiful celebration of and tribute to the incredible, out-of-control exuberance expressed by the Creator through the various living things in our world. Wild asses, storks, rock badgers, lions, Leviathan.

As Annie Dillard wrote in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, her Pulitzer Prize winning testament to the wonders of the natural world, “Look, in short, at practically anything—the coot’s feet, the mantis’s face, a banana, the human ear—and see that not only did the creator create everything, but he is apt to create anything. He’ll stop at nothing. There is no one standing over evolution with a red pencil to say: ‘Now, that one, there, is absolutely ridiculous, and I won’t have it.’”

As I look out at the menagerie of animals, humans included, who are attending church today I see an embodiment of the Psalmist’s final reflection:

When you send forth your spirit, they are created;

and you renew the face of the earth.

May the glory of the Lord endure for ever;

may the Lord rejoice in his works.

It is Saint Francis Sunday; knowing that this is Marsue’s favorite Sunday of the year, I was greatly and pleasantly surprised when she asked me a few weeks ago if I would like to give the sermon today. In preparation, I’ve had an opportunity to think about the animals, past and present, in my life. Each of you has an animal or two in your life that has changed who you are. In my life there are two such animals.

One of them, Frieda, accompanied Jeanne to the lectern to read from Genesis 1 a few moments ago. The other animal who changed my life was my childhood cat. How can an overweight, close-to-obese cat who died almost thirty-five years ago occupy a central place in my history? Allowing for imperfect memory, by my unofficial count I have had at least a dozen cats and dogs as pets since she died, but Stokely is the center of gravity in the menagerie of four-leggers that has intersected with my life. Remembering Stokely connects me with the better parts of my youth—humor, laughter, my father at his best. In a strange way, Stokely also makes me think differently about what God might be up to with us human beings. Not bad for a cat.

Stokely almost didn’t end up in my life at all. In the summer between my sixth and seventh grade years, my family moved about 40 miles north, from a rural and isolated location to what serves in Vermont as suburbia. One of our two dogs had died during the previous year; our other dog, an elderly collie who was strongly attached to our next door neighbor, was deemed too old to make the move and stayed with the neighbor.

Petless for the first time in my life, I asked for a cat. There had never been a cat in my world—I didn’t even know anyone with a cat. But I thought a cat would be cool. My father did not. He also had never had a cat, and my request struck him as another odd, peculiar request from his youngest son who would not hunt, tended to be overly emotional, and just didn’t fit his mold of a typical son. And now he wanted a cat instead of a dog, for God’s sake.

I worked on Dad all summer, and knew I had him when he proposed one of his random, off-the-wall bargains. “We can get a cat if he’s black and if we name him Stokely after Stokely Carmichael.” This was 1967, and the civil rights movement was in full swing. In my father’s peculiar imagination, a black cat named after one of the infamous Black Panthers made sense. Why he didn’t propose “H. Rap,” “Eldridge,” “Malcolm,” or even “Dr. King,” I don’t know. “Bruce!” my mother complained. “Good grief,” my brother sighed. “Deal,” I said—we were going to get a cat.

A few weeks later my cousin reported that her co-worker at the local hamburger joint owned a cat that had just produced kittens. The litter had three calicoes with various patterns of white, brown, and yellow and Stokely—all black except for a bit of white on his chest. Stokely’s eyes had just opened a few days earlier and he could barely walk. I deposited him in a box with a bag of dry food from my cousin’s friend, jumped in the car and my mother drove us home.

Stokely was an attraction in my extended family, none of whom had ever had a cat and none of whom could believe that my Dad, the unofficial patriarch of the extended family, had agreed to have one in his house. A few days later, My aunt picked Stokely up by the scruff of the neck (we had heard that cats like that) and let him hang from her hand—“There’s a problem here!” she announced. “Notice anything missing?” I didn’t, but my brother did—“Stokely’s a girl!”

Not only did Stokely turn out to be a different gender than we had ordered, she turned out not even to be black. She was a calico just like her litter mates—what appeared to be solid black was predominantly dark brown, which became more and more flecked with white, cream, and yellow highlights as she grew up. Her toes were colored individually, with a dark brown, light brown, yellow, and white one on each foot in no particular order. My ever-observant father said that she looked like she was assembled out of spare parts.

In her later years, Stokely became extraordinarily fat. From her early years, she exhibited a personality that matched her appearance. Cats are supposed to be graceful—Stokely was clumsy. Cats are supposed to land on their feet when falling from heights great and small—my brother and I verified by experimentation over and over that Stokely was as likely to fall on her side or even her back as on her feet when dropped from various heights onto my bed. I saw Stokely tumble down the stairs leading to our front door landing more than once when a too-vigorous post nap stretch unexpectedly dislodged her from her spot in the sun on the top stair. Cats are supposed to be introverts and avoid loud noises, but Stokely would run from anywhere in the house so she could ride on the Hoover while my mother vacuumed the floor.

A couple of years ago, I asked Marsue in an email for some input on a tough decision that I had to make. She responded that “I find it part of God’s playfulness to just put things out there for which we might be put to good use, stand back and watch how we handle what has come our way.” A playful God who might be entertained and amused by how we handle new situations is non-traditional, to say the least, but I completely understand the dynamic. My father, brother and I took endless delight—to my mother’s dismay—in slightly rearranging Stokely’s world occasionally to see what she would do. A piece of scotch tape on her back foot or ear, depositing her on top of the piano, putting a cat sized coat on her for the first time—always produced gales of laughter as Stokely first gave us a “when are you bastards ever going to grow up?” look, then deliberately addressed the new challenge at hand.

A good thirty-five years after her passing, my crystal-clear memories of this obese, made-out-of-spare-parts animal are evidence that she had an impact on me. As I’ve thought about her this week, I’ve become more and more convinced that we are all Stokelys. Although I suspect that most of us would like to believe that we are integrated, focused and sharply defined, we really are little more than random collections of spare parts—most of which are not of our choosing. We do not choose our families, the place and time of our births, our race, our gender, and yet out of these assigned parts—along with those we do have some choice in—we are given the task of constructing a life.

And overseeing all of this is something greater than us whose idea of planning and design is apparently something like “How about if I throw a whole bunch of odds and ends together and see what happens?” Psalm 139 says that we are “fearfully and wonderfully made.” If God takes delight in seeing what we make of the bits and pieces we have been given, perhaps we should as well.