One of my greatest joys as a philosophy professor is that I get to be bad on a regular basis. There were a number of people about whom I was told little growing up, other than that they are dangerous and to be avoided like the plague. I work out my rebellion against these restrictions now by ensuring that these thinkers make as many appearances on my syllabi as professional integrity will allow.

So I teach Darwin with gusto in the interdisciplinary program I participate in, and took great delight in hearing an older Benedictine monk—a biologist by training—once say that “Darwin has taught us more about God than all the theologians put together.” I take a perverse pleasure in making sure that my mostly parochial school educated students know that Marx is not just a four-letter word and, more importantly, is not an irrelevancy simply because the Berlin Wall fell 30 years ago.

I’m hoping that it is more than a perverse contrariness that caused me to place books by Sigmund Freud, Richard Dawkins, and Daniel Dennett on the syllabus a few years ago for the semester spent studying contemporary philosophy of religion with 20 senior philosophy majors. I must admit, though, that I enjoyed seeing the shocked faces of the six Catholic seminarians in the class when they saw the syllabus.

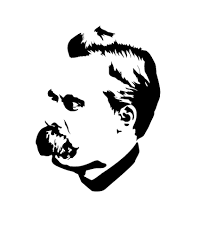

Yesterday I had the privilege of introducing a bunch of sophomores to the most thinker of all: Friedrich Nietzsche. The extent of my knowledge of Nietzsche growing up was at roughly the depth of the graffiti that I occasionally find on the wall in a men’s bathroom stall:

God is Dead: Nietzsche

Nietzsche is Dead: God

Although no one ever actually said so, I assumed that not only was Nietzsche dead but he was struck dead by God as soon as he wrote the blasphemous phrase. If God struck Uzzah for putting his hand on the ark of the covenant in Second Samuel because it was going to tip over, then imagine what happened to Friedrich. How was I to know that once I met him in college, Friedrich and I would become friends? And especially who would have thought that not only is “God is dead” not blasphemous, but also that in many important ways it is profoundly true?

Nietzsche has been dismissed as one of the most virulent and rabid atheists in the history of the West, both by people (like the graffiti artist) who have never read a word Nietzsche wrote and by agenda-driven scholars and believers who, having read the man’s work, should know better. And, indeed he was an atheist. It is only through many years of reading Nietzsche, trying to separate the abundant chaff from the even more abundant wheat, teaching his thought to undergraduates, and especially by taking his infamous “God is dead” seriously, that I’ve come to understand what Simone Weil meant when she wrote that “atheism is a purification.”

Nietzsche was one of the most God-obsessed thinkers who ever lived—he was not making the absurd claim that there once lived in heaven an old guy who died toward the end of the nineteenth century. Rather, “God is dead” is a devastating three-word commentary on what happens when, without our noticing, an idea, a concept, a picture loses its ability to move and inspire.

I have sought, in various ways, to be serious about the sacred, about what transcends us, for as long as I can remember. This requires consciously challenging my assumptions, representations, and practices concerning the sacred in a consistent and courageous way. Despite wanting to believe that I am a cutting-edge, liberal, creatively out-of-the-box thinker, I am often encouraged to press further when helped by those who are outside every box imaginable. Nietzsche provides that help more than anyone I’ve encountered, the insistent voice of a half-crazy relative saying “Are you sure? Is that life-affirming? Does that matter? How’s lugging that corpse around 24/7 working for you?”

Although I’m not a Nietzsche scholar in the narrow and deep academic sense, I enjoy teaching Nietzsche more than just about any philosopher. I’ve told colleagues that if you can’t get students worked up about Nietzsche in class, you should go into a different profession. Yet it took several months of sabbatical at an ecumenical institute on the campus of a Benedictine college and abbey a decade ago for me to begin coming to personal grips with “God is dead” in my own life. At that time, I made a partial list of the divine corpses in my history, a list that I continue to revise and add to:

- A now silent God who stopped communicating directly with human beings several centuries ago, once the dictation of the divine word in print was finished.

- A God who invites into the inner sanctum only those who have a special “prayer language.”

- A God who “is not willing that any should perish, but that all should come to repentance,” but who at the same time is so judgmental and exclusive that the vast majority of the billions of human beings who have ever lived will end up in hell.

- An exclusively masculine God.

- A God who is more concerned with the length of male hair and female skirts than with the breadth and depth of one’s spiritual hunger and desire.

- A God whose paramount concerns are one’s positions on sexual orientation, same-sex marriage, abortion, or universal health care.

- A God who micromanages every detail of reality at every moment, including tsunamis, birth defects, and oil spills.

- A God who is more honored by self-reliance than by compassion for those in need.

- And, most recently, a God who supposedly ordained Donald Trump to be President.

Marcus Borg once wrote that when talking with someone who claims not to believe in God, he would ask that person to describe the god she or he does not believe in. He invariably responded to their description with “I don’t believe in that God either.” Makes sense.

Joan Chittister says that “our idea of God is the measure of our spiritual maturity.” For most of my adult life, I was locked into perpetual spiritual childhood by various ideas of God that correspond to nothing living. By finally saying that “these Gods are dead” and meaning it, I did not commit myself to a denial of the sacred—just attendance at the funeral of particular conceptions of God. And this is an intensely and exclusively personal death. I have relatives who grew up breathing the same religious atmosphere I did, who in their adult lives continue to be nourished and supported by belief in and worship of the very same God whose funeral I mark regularly. I honor, and perhaps even am slightly envious of them. But I will no longer sit in the back of a funeral parlor waiting for something to happen.

“Atheism is a purification” marks a period of transition from a funeral to signs of life. The God who is not dead has many traits that am continually discovering, now that the funeral are over. The best place for me to start, when on that sabbatical a decade ago, was with the appealing possibility that God, rather than angry and judgmental, meets my deep need for acceptance and love. I still continue to keep my eye out for dead Gods. Many years ago, a book called If You Meet the Buddha on the Road, Kill Him! was all the rage. That’s too aggressive for me, but I get the point. If I meet God along the road, I’ll at least check to see if she has a pulse.