A thing about dying is that you can’t consult anyone who has done it. Peter Schjeldahl

A friend who was the junior warden at Trinity Episcopal Church where Jeanne and I worship died last week after an extended battle with cancer. His funeral mass was this past Monday. Don was in his seventies and had been a member of the church since his youth. Needless to say, he was a fixture. At the end of the liturgy, as Don’s casket was about to be rolled down the aisle then to take Don for the final time from Trinity, the priest read the commendation from the prayer book.

We are mortal, formed of the earth, and to earth shall we return. For so did you ordain when you created us, saying, “You are dust, and to dust you shall return.” All of us go down to the dust; yet even at the grave we make our song: Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia.

Today is Holy Saturday, a good day to once again be reminded that we are mortal and that, despite what we anticipate happening tomorrow, we all will die. Quoting the Book of Job, the Holy Saturday liturgy reminds us that

Mortals die, and are laid low; humans expire, and where are they? As waters fail from a lake, and a river wastes away and dries up, so mortals lie down and do not rise again; until the heavens are no more, they will not awake or be roused out of their sleep.

Those who loved and followed Jesus, both those who fled and those who stayed, could not have escaped these truths on the day after Jesus was crucified and laid in the tomb. The German theologian Jürgen Moltmann once wrote that all honest theology had to be conducted “within earshot of the dying Jesus.” Those who remained the day after Jesus’ execution literally were within earshot of the dying Jesus—I’m sure his cries of suffering and abandonment were still ringing in their ears. And they should be in ours today. As Christian Wiman notes, “resurrection is a fiction and a distraction to anyone who refuses to face the reality of death.” Human beings die and are laid low. And Jesus was a human being.

The 12/23/19 edition of The New Yorker led with a remarkable and memorable essay by Peter Schjeldahl, who has been the magazine’s art critic for the past twenty years. The essay, “77 Sunset Me” (it’s subtitled “The Art of Dying” in the Table of Contents), is Schjeldahl’s memoirish reflection on vignettes of his life after having received a diagnosis of terminal lung cancer. The essay is honest, often brutally so, and full of wisdom both hilarious and poignant.

About halfway through his lengthy essay, Schjeldahl notes his agreement with one of Simone Weil’s most striking claims. “Simone Weil,” he writes, “said that the transcendent meaning of Christianity is complete with Jesus’ death, sans the cherry on top that is the Resurrection. I think so.” The actual passage from Weil, from a letter she wrote to a Dominican priest friend, is as follows:

Hitler could die and return to life again fifty times, but I should still not look upon him as the Son of God. And if the gospel omitted all mention of Christ’s Resurrection, faith would be easier for me. The Cross by itself suffices me.

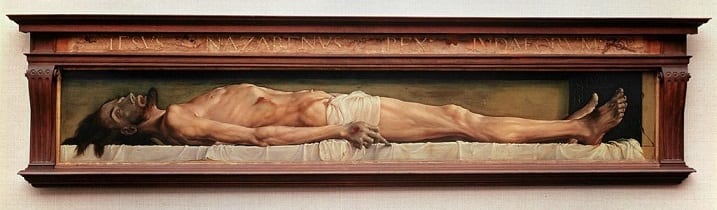

Schjeldahl reflects on this passage after noting, as both an art critic and a man who is dying, on the power of Hans Holbein’s “Dead Christ,” a painting that reportedly shook Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Christian faith.

Dostoevsky viewed the painting in 1867, when he visited the Basel Art Museum. His response was so intense, that his wife became concerned. She reported that he turned white and refused to leave, she dragged him away concerned that his heightened emotions might bring on an epileptic fit. He later remarked that, “Such a picture might make one lose one’s faith.”

A character in Dostoevsky’s 1868 novel The Idiot has the following reaction to a print of Holbein’s painting, undoubtedly expressing Dostoevsky’s own reaction a year or so earlier:

Supposing that the disciples, the future apostles, the women who had followed Him and stood by the cross, all of whom believed in and worshipped Him—supposing that they saw this tortured body, this face so mangled and bleeding and bruised (and they must have so seen it)—how could they have gazed upon the dreadful sight and yet have believed that He would rise again?

Clearly, the most likely answer is that “they couldn’t.” And they didn’t. There is no indication in the gospels that, despite various things that Jesus had said in the previous months, anyone really believed that he was anything but dead for good. As the disciples walking toward Emmaus in Luke’s gospel tell the resurrected but unrecognized Jesus, “We had hoped that it was He who was going to redeem Israel.” And he died. And he’s rotting in a tomb.

It is clear throughout his novels that Dostoevsky believed confronting doubts was a central part of faith. Dostoevsky believed that faith wasn’t bolstered by finding evidence for God, but in believing despite the evidence against story. That helps explain Dostoevsky’s response to this work. The depiction of the dead Christ is so realistic, so jarring, that it is a challenge to one’s faith to continue to believe in the resurrection. Our eyes and our experience with death tells us that death is final, there can be no reversal of death to life. Mortals die, and are laid low.

In The New Yorker article, Peter Schieldahl notes that although he was raised Lutheran, he tried atheism on for size as a young adult. But it didn’t take. Although he does not attend church and treats God on an “as if” basis, Schieldahl makes a striking observation toward the end of the article.:

God creeps in. Human minds are the universe’s only instruments for reflecting on itself. The fact of our existence suggests a cosmic approval of it . . . We may be accidents of matter and energy, but we can’t help circling back to the sense of a meaning that is unaccountable by the application of what we know.

In an NPR interview a few days after the article was published, Scott Simon asked Schjeldahl to say more about what he meant when he wrote that “God creeps in.” Schjeldahl answered that

I think we’re wired for belief, and it’s sort of human pride and ambition to overrule those intuitions. But I find it much easier just to give in. We are tiny, little specks in the universe, and there is a credible limit to what we know. And in a way, the more we know, the more shoreline of mystery there is . . . Human minds are the only ways the universe reflects on itself. And we keep circling back to that – you know, why we’re here and not here. And I’m – I guess I’m sort of relaxing into the state of soul that that generates.

I would like to think that a diagnosis of terminal cancer is not required in order to find the ability to “relax into the state of soul” that is open to the possibility of God in a welcoming, nondogmatic way, a state of soul that invites us to walk barefoot along the “shoreline of mystery.”

Since, as Schjeldahl notes, “a thing about dying is that you can’t consult anyone who has done it,” we are all in the same boat—mortal, self-reflective creatures with a short shelf life and limited knowledge. It makes sense to be open to God creeping in. Schjeldahl ends his essay with a bit of advice and an observation.

Take death for a walk in your minds, folks . . . If God is a human invention, good for us! We had to come up with something.

Yet even at the grave we make our song: Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia.