I recently had the opportunity to have a face-to-face conversation with the new Provost at my college. For those unaware of what a Provost is or does, the Provost is the top academic officer at a college or university. She or he is, or at least attempts to be, the liaison and bridge between the faculty and the administration. It a very tough and often thankless job. I had the opportunity for many reasons to interact with our previous Provost, who retired a bit over a year ago, frequently over a couple of decades. It often seemed to me that a good decision from the Provost’s office is similar to what a Supreme Court justice once said about decisions from the highest court in the land. A good decision is one that no on on any side is happy with.

My conversation with our new Provost covered a lot of ground over two hours. He has been Provost for a year, but due to Covid-19 restrictions, we had never met in person. We’d seen each other in various Zoom meetings during the 2020-21 academic year, but you don’t really get to know somebody by looking at a square on a computer screen. He described our meeting as part of his “listening tour”–getting the lay of the land at the college by talking to various people who had been around for a while and had held various different positions. That would certainly include me–I’ll be starting my 28th year at the college at the end of this month.

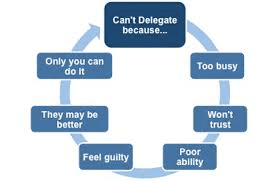

We talked a lot about leadership styles, which has caused me over the month since our conversation to reflect back on the various times that I was in a leadership role on campus. I did not go into academia to be an administrator, so I pretty much learned what I know about leadership on the fly by trial and error. I learned, for instance, that one of the most important things that any administrator or leader needs to learn is how to delegate authority.

This advice has become a standard part of the package of wisdom passed from experienced administrators to those who follow them—you can’t do this alone. It was a central part of the advice I gave both the colleague who followed me as chair of the twenty-two member philosophy department when my four-year stint ended several years ago, as well as what I told the new director of the much larger interdisciplinary program with eighty faculty and 1,800 students I directed for four years after my department chair years. It is indeed essential information to pass on to the next administrator, and I talked a good game. But delegating has always been a challenge for me.

I remember the day while directing the interdisciplinary program when, in the midst of trying to juggle several meetings that week, the scheduling of forty teams of three faculty each for the next academic year, upwards of two hundred emails every morning, and the demands of my own classes, I pushed back from my office computer and said I. CAN’T. DO. THIS” (I might have thrown in an F-bomb between “Can’t” and “Do”). And a little voice inside my head said “No kidding, moron!” (my inner voice is surprisingly disrespectful). “You’re trying to do it all yourself, which is not only dumb, it’s impossible.” I had an assistant director and a program administrative assistant I was not utilizing fully, and I was not making sufficient use of any number of committees whose sole purpose for existence was to perform some of the important duties I was doing myself.

Why was I making things so hard on myself? Perfectionism. Control. Introversion. The belief that the only way to guarantee things get done right is to do them myself. I knew all of these things about myself and still was driving myself unnecessarily nuts. But in one of those strange “coincidences” that happen so often that I suspect they are not coincidences, it was my turn to be lector at church the next Sunday. The assigned readings were all about–you guessed it–how to delegate authority.

The first reading that Sunday was from the Book of Numbers in the Jewish Scriptures. We find the liberated Israelites in the desert, and they are complaining—again. God has miraculously provided them with a daily supply of manna—miracle food from heaven—to keep them from starving, but everyone is pining for the wonderful variety of food they remember eating in Egypt.

We remember the fish we used to eat in Egypt for nothing, the cucumbers, the melons, the leeks, the onions, and the garlic; but now our strength is dried up, and there is nothing at all but this manna to look at.

Of course they have conveniently forgotten that when they were in Egypt they were freaking slaves. God is understandably annoyed (this is not the first time these complaints have arisen), and so is Moses. But Moses’ annoyance isn’t just with this rabble of complainers he is in charge of; he’s had it up to here with the Big Guy as well.

“Have I done something to annoy you that I’m not aware of?” Moses wants to know. “Because otherwise I can’t explain why you have dumped all of this crap on me. Did I create these people? Am I the one who promised them freedom, a new land, and all the rest? News flash—that was YOU! But are you the one who has to solve everyone’s problems and wipe everyone’s butt for them? No—that would be ME!” And in a classic drama queen moment, Moses collapses on the spot.

I am not able to carry all this people alone, for they are too heavy for me. If this is the way you are going to treat me, put me to death at once–if I have found favor in your sight–and do not let me see my misery.

In response to Moses’ tantrum, God does what God often does in such situations in the Jewish Scriptures, and makes it up as he goes along. “What if I take some of the power and authority I’ve given you and distribute it to some carefully selected folks so they can share the burden of leadership and responsibility with you?” God suggests—and delegation is invented. Moses selects seventy guys he trusts, brings them to the tent of meeting (the place where God and humans officially interact), the Lord empowers the seventy men in response to which they start “prophesying,” and a solid chain of command and power sharing structure is established.

A few things to note:

- Authority and power appear to be zero sum, meaning that empowering others automatically means that the leader is disempowered to that same exent. Only secure people should be in leadership roles, in other words.

- Power needs to be distributed carefully, publicly, and according to recognizable procedures. A ceremony to mark the empowerment is a good idea.

- Others need to be clearly made aware of the new power structure. The “prophesying” part of the story means, at the very least, that the newly empowered have been publicly marked as such. Secretly adding layers of bureaucracy without transparency is a recipe for suspicion and resentment.

This all sounds eminently sensible—until problems arise in the very next verses.

It turns out that two of the guys selected by Moses for empowerment didn’t make it to the tent of meeting, but they start prophesying in the camp as if they had participated in the official empowerment ceremony. In other words, they are acting with authority without having been officially empowered. Moses’ number one assistant, Joshua, squeals on the two guys to Moses and asks for permission to stop the unauthorized activity of these posers and frauds.

Surprisingly, Moses tells Joshua to leave them alone. “Are you jealous for my sake? Would that all the Lord’s people were prophets, and that the Lord would put his spirit upon them.” In the short span of one story authority has shifted from one person to the vision of a projected future in which anyone who has the vision and ability to be effective can act on it. What about the hierarchy? What about keeping tight control on how power is distributed? Is this any way to run an organization?

Apparently it is. In that same Sunday’s gospel, similar issues arose. Jesus has empowered his disciples to preach the gospel, cast out demons, and heal the sick—so far, so good. Then John reports some disturbing news to Jesus: “Teacher, we saw someone casting out demons in your name, and we tried to stop him, because he was not following us.” John, presumably speaking for the rest of the group, assumes that only those specifically authorized and empowered by Jesus to do special stuff should be doing it. This stranger using Jesus’ name to cast out demons is guilty of spiritual plagiarism, in other words. He hasn’t even learned the secret disciples’ password or handshake. And just as Moses told Joshua, Jesus tells John and the rest to leave this guy alone. “Whoever is not against us is for us.”

As we often learn when reading stories about the intersection of the human and the divine, things divine operate according to entirely different rules than those to which we are accustomed. Or perhaps according to no recognizable rules at all. The divine spirit is frequently likened to the wind, which blows where it wants when it wants to, without regard to our expectations, desires, or weather predictions. The takeaway? Divine power and authority is not a zero sum game. It can and will show up in all sorts of unlikely places, even those we have not authorized. Especially in those places.