This past weekend, Jeanne and I, along with our two sons and our daughter-in-law, travelled from Providence to Long Island for the wedding of one of Jeanne’s nieces. It was the first time the five of us had been together since last Christmas, and the first time we had all been together in Providence in over two years. Jeanne is the youngest of five; the wedding offered the rare opportunity for all five of the siblings to be together in the same place.  Their ages range from 80 to 65, so it was hard not to wonder whether this might be the last time all five of them are together. Difficult conversations that might have been morbid when younger become no less difficult, but much more natural, as we age. Such is the nature of mortal creatures.

Their ages range from 80 to 65, so it was hard not to wonder whether this might be the last time all five of them are together. Difficult conversations that might have been morbid when younger become no less difficult, but much more natural, as we age. Such is the nature of mortal creatures.

The 12/23/19 edition of The New Yorker leads with a remarkable and memorable essay by Peter Schjeldahl, who has been the magazine’s art critic for the past twenty years. The essay, “77 Sunset Me” (it’s subtitled “The Art of Dying” in the Table of Contents), is Schjeldahl’s memoirish reflection on vignettes of his life after having received a diagnosis of terminal lung cancer not long ago. The essay is honest, often brutally so, and full of wisdom both hilarious and poignant. As a bonus, Schjeldahl references both Michel de Montaigne and Simone Weil, the two philosophers who have, over the past many years, influenced my own thought and life more than any others. I taught an honors colloquium on Montaigne last spring, and Simone makes it into my writing and classes on a regular basis (yes, she and I are on a first-name basis).

About halfway through his lengthy essay, Schjeldahl notes his agreement with one of Weil’s most striking claims. “Simone Weil,” he writes, “said that the transcendent meaning of Christianity is complete with Jesus’ death, sans the cherry on top that is the Resurrection. I think so.” The actual passage from Weil, from a letter she wrote to a Dominican priest friend, is as follows:

Hitler could die and return to life again fifty times, but I should still not look upon him as the Son of God. And if the gospel omitted all mention of Christ’s Resurrection, faith would be easier for me. The Cross by itself suffices me.

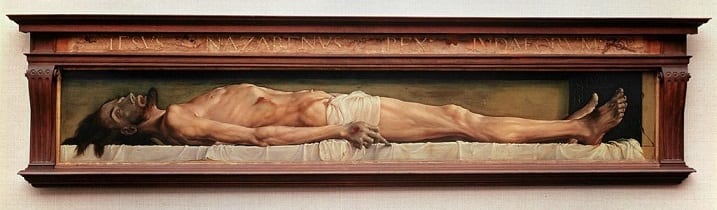

Schjeldahl reflects on this passage after noting, as both an art critic and a man who is dying, the power of Hans Holbein’s “Dead Christ,” a painting that reportedly shook Dostoevsky’s Christian faith.

“I believe in God” is a false statement for me because it is voiced by my ego, which is compulsively skeptical. But the rest of me tends otherwise. Staying on an “as if” basis with “god,” for short, hugely improves my life. I regret my lack of the church and its gift of community. My ego is too fat to squeeze through the door.

His point is worth considering for all who seek to locate themselves within the context of the transcendent. Whether one is an atheist or the most dogmatic and hard-core person of faith, what Iris Murdoch calls the “fat, relentless ego” always threatens to get in the way. One person’s need to be right, to be certain, and to defend that unwarranted certainty against all comers, just as much as another person’s dogmatic commitment to skepticism, regularly guarantees that our other ways of knowing, our “rest of me,” will get pushed to the side.

Schjeldahl continues by noting that, at least in his experience, the fat ego’s need to dominate belief fades with accumulating years, experience, and maturity.

Disbelieving is toilsome. It can be a pleasure for adolescent brains with energy to spare, but hanging on to it later saps and rigidifies. After a Lutheran upbringing, I became an atheist at the onset of puberty. That wore off gradually and then, with sobriety, speedily.

Christian Wiman, who has a poem in the same New Yorker as Schjeldahl’s essay, writes in My Bright Abyss that he shares Schjeldahl’s perspective when it comes to God. “Mostly I simply try to subject myself to the possibility of God. I address God as if.” Makes sense to me.

At the end of “77 Sunset Me,” Schjeldahl makes a striking observation:

God creeps in. Human minds are the universe’s only instruments for reflecting on itself. The fact of our existence suggests a cosmic approval of it . . . We may be accidents of matter and energy, but we can’t help circling back to the sense of a meaning that is unaccountable by the application of what we know.

In an NPR interview ten days ago, Scott Simon asked Schjeldahl to say more about what he meant when he wrote that “God creeps in.” Schjeldahl answered that

I think we’re wired for belief, and it’s sort of human pride and ambition to overrule those intuitions. But I find it much easier just to give in. We are tiny, little specks in the universe, and there is a credible limit to what we know. And in a way, the more we know, the more shoreline of mystery there is . . . Human minds are the only ways the universe reflects on itself. And we keep circling back to that – you know, why we’re here and not here. And I’m – I guess I’m sort of relaxing into the state of soul that that generates.

I would like to think that a diagnosis of terminal cancer is not required in order to find the ability to “relax into the state of soul” that is open to the possibility of God in a welcoming, nondogmatic way, a state of soul that invites us to walk barefoot along the “shoreline of mystery.”

Since, as Schjeldahl notes, “a thing about dying is that you can’t consult anyone who has done it,” we are all in the same boat—mortal, self-reflective creatures with a short shelf life and limited knowledge. It makes sense to be open to God creeping in. Schjeldahl ends his essay with a bit of advice and an observation.

Take death for a walk in your minds, folks . . . If God is a human invention, good for us! We had to come up with something.