This is the first week of the best four weeks of the year: March Madness. This week is called “Championship Week,” when the thirty-or-so Division One basketball conferences play their post-season tournaments. The winners of those tournaments plus an equal number of other worthy teams get to play in the NCAA basketball tournament that starts next week. This coming Sunday is “Selection Sunday,” when the participants in the NCAA tournament will be announced, as well as brackets and seeding. Many people consider Sunday to be a “holy” day—Selection Sunday is holier than most.

While watching four straight games in the Big East basketball tournament yesterday, including my Friars’ win which launched them into the semifinals this evening, I occasionally wondered—as I often do—why sports in general and college basketball in particular is so important to me. The answer is simple—sports fanaticism is good for you.

March is a great month for sports fanatics. Pro basketball and hockey are in full swing, and we just learned yesterday that despite a labor stoppage, we’re going to get a complete season of baseball this year after all. If you don’t care about any of that, then (1) I feel sorry for you and (2) what is wrong with you? But read on, because I will explain to you why you might want to care about sports anyways. I am both a sports fanatic and a person of faith. Despite appearances, they complement each other. Indeed, my sports fanaticism provides me with ways to be and to grow that nothing else offers. For me, sports fanaticism is a spiritual practice.

I am not an athlete—the only sports I ever have been any good at—skiing and tennis—are individual sports. My greatest personal achievement in team sports was as the starting first baseman for one year on my town’s Little League team (and that’s because I had a first-baseman’s glove—no one else did). I grew up in northern New England, hundreds of miles from any sports beyond high school. But I was a fan of all sports from an early age, a fanaticism that has distilled, as an adult, to the Boston Red Sox and the Providence Friars.

My passion for college basketball in general, and the Friars in particular, surprised my students and colleagues when I first arrived on campus twenty-eight years ago, although my colleagues, at least, should not have been surprised. During a lunch with the philosophy faculty that was part of my on-campus interview in February 1994, someone asked “why do you want to teach at Providence College?” My most obvious answer would have been that I wanted a tenure-track job somewhere other than in Memphis, Tennessee, where we were situated at the time. I think the continuation of my marriage depended on it.

The answer I actually gave included making some noise about wanting to teach at a place that takes philosophy seriously, focuses on the history of philosophy, and so on. On a more personal level, I continued, my wife and I badly wanted to return to our native Northeast (she’s from Brooklyn, I’m from Vermont). I concluded my response by mentioning that Division One basketball was also a very attractive feature of working at Providence College. There were a few snickers and smiles—but I wasn’t kidding.

I’m a different person entirely at a basketball game. It’s a great place for my inner beast to come out—even introverts have one—in ways that sometimes even I am surprised by. Once during our second year at Providence, when my season tickets were still in an upper deck nosebleed section, we were given two seats on the court by the Admissions Director Jeanne worked for. It was not a pretty game—we were being beaten by Iona. Providence should never be beaten by Iona, so obviously it was the referees’ fault.

After a particularly horrendous call, one of the zebras went trotting by our seats, just a few feet away, causing me to scream in his direction, along with several thousand other fans, about what was on my mind. A few seconds later I asked Jeanne “Did I just call the ref a f–king asshole?” “Yes, you did,” she replied. That’s why I love basketball games—they provide the opportunity for unfiltered expression of what I really am feeling and thinking. Later in the game I looked up toward our usual seats where my son Justin was sitting. As he screamed with a beet-red face and veins popping out of his neck, I wondered “Why is he getting so upset? It’s just a game. Where does he get that from?”

I have had two season tickets in Section 104 for the past twenty-six years. Section 104 is a family section—if your family has a “Sons of Anarchy” feel to it. Once several years ago a young man a couple of rows in front of me, the son of one of the season ticket holders, was telling a story to a friend during a timeout with all the energy, volume, and foul language that a half-inebriated twenty-something male can muster. “HE SAID BLAH BLAH BLAH SO I SAID GO F–K YOURSELF! THEN HE SAID BLAH BLAH BLAH SO I SAID GO F–K YOURSELF!!” After a few more GFYs, a guy in the front row of the section turned around and yelled “Hey! Knock it off! I’ve got my wife with me!” The young guy apologized—“sorry, man”—but front row guy wouldn’t let it go and kept complaining. Before long, GFY guy goes “I SAID I WAS SORRY!! GO F–K YOURSELF!!” I love Section 104.

You may be thinking by now that this doesn’t sound very much like the spiritual practice that I referenced early on. I beg to differ. “Spiritual practice” is usually associated with prayer, meditation, saying the rosary, lectio divina, or any activity that arguably takes one “out of oneself” in a direction that points toward God.  Being a sports fanatic takes me out of my head and lets me be present without reservation in a way that virtually nothing else does. Sports fanaticism reminds me that I’m more than a brain, more than the sum total of the roles I play, even though I love every one of them. Being a fan reminds me that there is still a kid inside who can get inexplicably excited, to the point of hyperventilation and tears, over something that makes no sense other than that I love it.

Being a sports fanatic takes me out of my head and lets me be present without reservation in a way that virtually nothing else does. Sports fanaticism reminds me that I’m more than a brain, more than the sum total of the roles I play, even though I love every one of them. Being a fan reminds me that there is still a kid inside who can get inexplicably excited, to the point of hyperventilation and tears, over something that makes no sense other than that I love it.

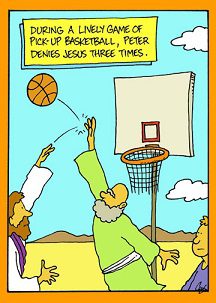

This, I submit, is remarkably close to how the life of faith sometimes can be. Surprising, holistic, revealing depths and features that go entirely unrecognized and unnoticed under “normal” circumstances. I’ve come to believe over the years that everything—absolutely everything—can be sacramental if one is willing to be open to such a possibility. Although winning is great, sports fanaticism is about far more than just that. It is about daring to be fully human in a world that doesn’t offer many opportunities to be so. I don’t know what sports Jewish guys in the first century C.E. played, but it would not surprise me if Jesus and the guys had a few pickup games when the opportunity arose.